Art World

This Edward Hopper Painting Has Been Called One of the ‘Ultimate Images of Summer.’ Here Are 3 Things You Might Not Know About It

During this summer of quarantine, we take a closer look at Hopper's 'Morning Sun.'

During this summer of quarantine, we take a closer look at Hopper's 'Morning Sun.'

Katie White

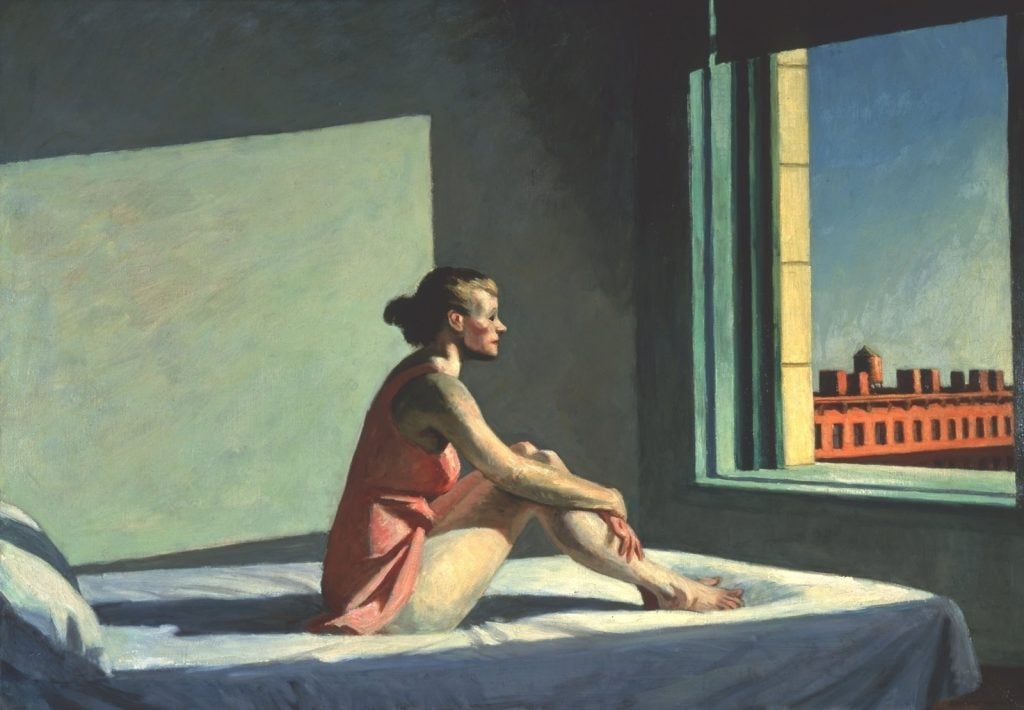

Edward Hopper’s paintings have long been beloved, but during quarantine, they have seemed suddenly new again. His isolated figures and emptied streets seem like uncanny snapshots of real life. And with summer upon us, Hopper’s 1952 painting Morning Sun strikes a particular chord—in fact, it’s been called it one of “the ultimate images of summer.”

In it, a woman, modeled on the painter’s wife, Jo, is pictured in a short pink slip, arms bare. She’s sitting up in bed with her knees pulled up to her chest, looking out her bedroom window into a city sky. Dramatic shadows are cast on the bare walls behind her.

The painting—in the collection of the Columbus Museum of Art since 1954, when it was scooped up for just $3,500—is Hopper at his best. It hints at the bare bones of a narrative with the kind of spare, evocative style that has since influenced filmmakers and photographers including Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, Wim Wenders, and Gregory Crewdson.

we are all edward hopper paintings now pic.twitter.com/gpcmSiavkD

— Michael Tisserand (@m_tisserand) March 16, 2020

Morning Sun is one of Hopper’s most well-known paintings. If you know his art, you probably know this image. Here are three facts about the painting that might make you see it in a different way.

Edgar Degas, Woman at a Window (1872). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Though considered the quintessential sturdy American realist, Hopper would say even late in life, “I think I’m still an Impressionist.”

He traveled to Paris frequently as a young artist. There, he was particularly awed by the work of Edgar Degas. Hopper shared Degas’s interest both in the theater—Degas loved the backstage at the ballet, Hopper’s art is full of cinemas—and the at-times crude pleasures of contemporary life. This influence was further cemented when in 1924, the year Hopper and Jo Nivison wed, she gifted him a copy of Paul Jamot’s Degas, an elaborate new publication on the painter.

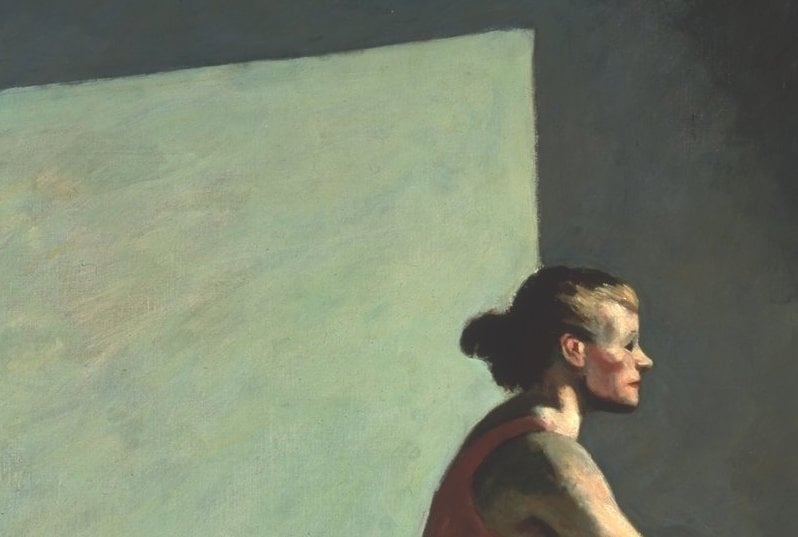

From Degas, Hopper adopted the strong use of diagonals and the severe, almost photographic cropping of the picture plane, visible here in Morning Sun the cutting off of the bed and window. A comparison might be Degas’s Woman at a Window (1872). There, a seated female figure has her profile thrown into relief by the window—though Degas opts for stylish shadow and Hopper for lucid light.

Detail of Edward Hopper, Morning Sun.

A voracious reader, Hopper named everything from dime-store pulp fiction to Hemingway to European philosophy and transcendentalist writings as his influences. His personal artistic philosophy came from literature too. He kept a quote from Goethe in his wallet and frequently referenced it: “The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me, all things being grasped, related, recreated, molded and reconstructed in a personal form and an original manner.”

For Hopper, the depiction of the world was a projection of his own mind—and in that sense he shared affinities with the abstract art movements taking place around him in New York during the 1940s and ’50s. Though Hopper infamously quipped that he’d never heard of Picasso while in Paris, he did not so much eschew Modern art as sample from it whatever elements he wished.

Especially in his later works, such as Morning Sun, light is depicted almost as an abstract object itself. In his essay “Hopper and the Figure of the Room,” art historian John Hollander writes of Morning Sun that the parallelogram of light cast against the wall behind Jo is “an image of the meditative gazer’s mind as the cast shadow on the bed is of her body.”

In that reading, you can almost think of the big area of light behind her as an empty comic book thought balloon. Consider how the fact that it takes up more space on the wall than the actual window certainly makes the painting read as focusing on her inner world, rather than the outer one.

Edward Hopper, Sun in an Empty Room (1963). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of Art.

Hollander continues, “the lightfalls bring rumors of Cubism, implications that some abstract art has been handed by history the keys to consciousness, to states of knowledge and feeling, that concrete, narrative externalizations had begun to betray and that landscape and still life would have to learn again to embody.”

For his part, Hopper never really went for abstraction, but his works became increasingly planar, culminating in Sun In An Empty Room (1963) in which a room much like in Morning Sun has been cleared of everything but light. “I guess I’m not very human,” he would say. “All I really want to do is paint light on the side of a house.” It’s easy to see how Abstract Expressionist artists such as Mark Rothko named Hopper among their big influences.

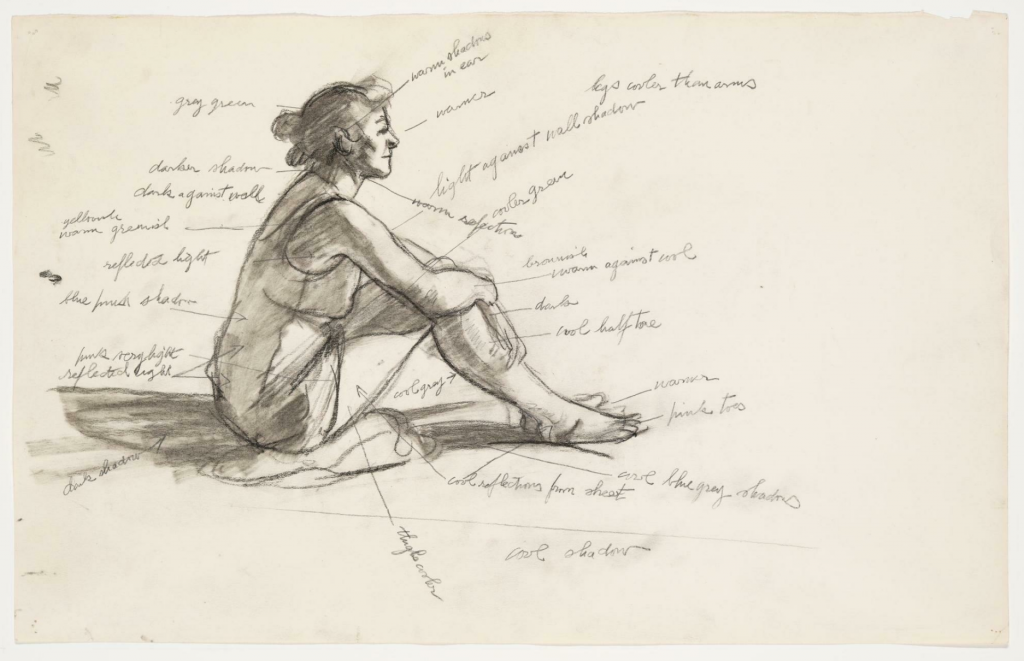

Edward Hopper, Study of Morning Sun (1952). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Much of Hopper’s early success can be attributed to Jo, his wife, manager, and the subject of this painting. By the time the couple married in 1924, both were in their 40s. Jo, a painter and actress, was the more established of the two. In 1923 she was invited to participate in a group exhibition of American and European artists at the Brooklyn Museum, and encouraged the curators to include her husband’s work as well. The exhibition resulted in the first museum acquisition of his work.

Jo was Hopper’s only female model from 1923 until Hopper’s death in 1967, though he never considered his paintings to be portraits of her, using her as a stand-in for “any woman.” At the time of the painting of Morning Sun, Jo was 69 years old, yet she is rendered in a rather idealized, youthful depiction. In Hopper’s sketches for the painting, you can see him abstract away the specifics of her, the better to give the scene a sense of being a larger, symbolic moment.

The couple’s relationship was tempestuous and at times violent, with Jo sacrificing her ambitions to manage Hopper’s career while keeping meticulous records of his completed works, exhibitions, and sales—even calling his paintings “their children.” Hopper in turn ridiculed Jo’s own paintings and sometimes forbid her from showing them. Once you know it, the backstory might give a whole different meaning to the ambiguous solitude of Morning Sun.