On View

Eloise, New York’s Favorite Child Aristocrat, Demanded a Museum Show. Now She’s Got One.

The show features a once-stolen painting of the precocious character, which hasn't been seen in public for 57 years.

The show features a once-stolen painting of the precocious character, which hasn't been seen in public for 57 years.

Sarah Cascone

A beloved New York icon is having a moment at the New-York Historical Society: Eloise, the famed children’s book character created by actress Kay Thompson (1909–1988) and illustrated by Hilary Knight (1926–) is the star of a new exhibition there, “Eloise at the Museum.”

The subject of four books, all published between 1955 and 1959—a fifth, unfinished manuscript, Eloise Takes a Bawth, was published by Thompson’s estate posthumously in 2002—the fictional Eloise is a six-year-old girl who lives with her nanny on the “tippy-top floor” of New York’s Plaza Hotel. There she gets up to all kind of mischief, including ordering lots and lots of room service—”charge it please, thank you very much.”

Eloise was an instant sensation upon her first appearance, in LIFE magazine, in 1955, with children clamoring to receive Eloise: A Book for Precocious Grown-Ups that Christmas. Essentially, she was the Cabbage Patch Kid or Tickle Me Elmo of her day.

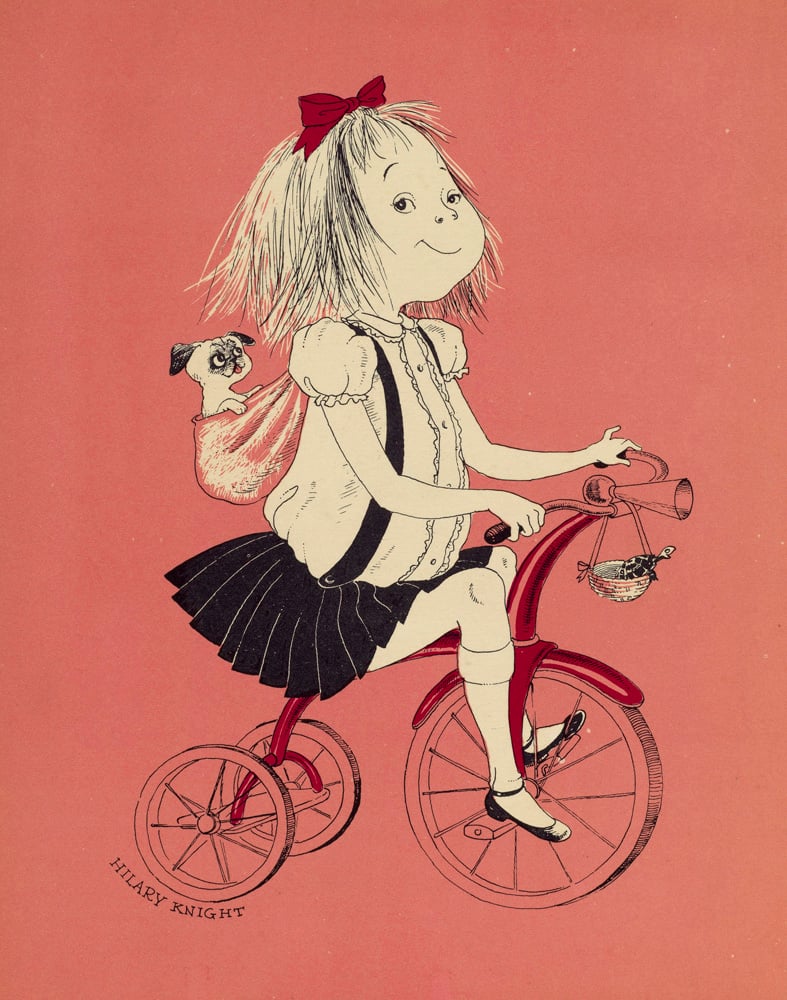

Hilary Knight, I have a dog that looks like a cat (circa 1954) for

Eloise, Simon & Schuster (1955). Collection of Hilary Knight, © Kay Thompson.

The character grew out of a voice that Thompson, a longtime Plaza Hotel resident, would perform for her friends. D.D. Dixon Ryan, Knight’s neighbor, encouraged her to turn it into a book and introduced her to the young illustrator while she was performing at the Plaza Hotel’s Person Room. Knight’s drawings perfectly captured Eloise’s impetuous spirit, and within a year they had a bestseller on their hands.

“They were the white-hot team,” said exhibition guest curator Jane Bayard Curley of the author/illustrator duo at a press preview for the show. “Everywhere you looked, there was Eloise.”

Hilary Knight, illustration of Eloise for the Plaza Hotel children’s menu, (1957-58). Collection of Hilary Knight, © Kay Thompson.

This is the second show she’s curated for the Historical Society, following 2014’s “Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans.” Both exhibitions originated at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was visiting the Madeline show that inspired Knight, according to Curley.

“At the end of the show, he turned to me and said, ‘Why can’t I have a show like that?'” she recalled. “Three years later, here we are!” (Knight is also currently the subject of the exhibition “Hilary Knight’s Stage Struck World,” at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts through September 1.)

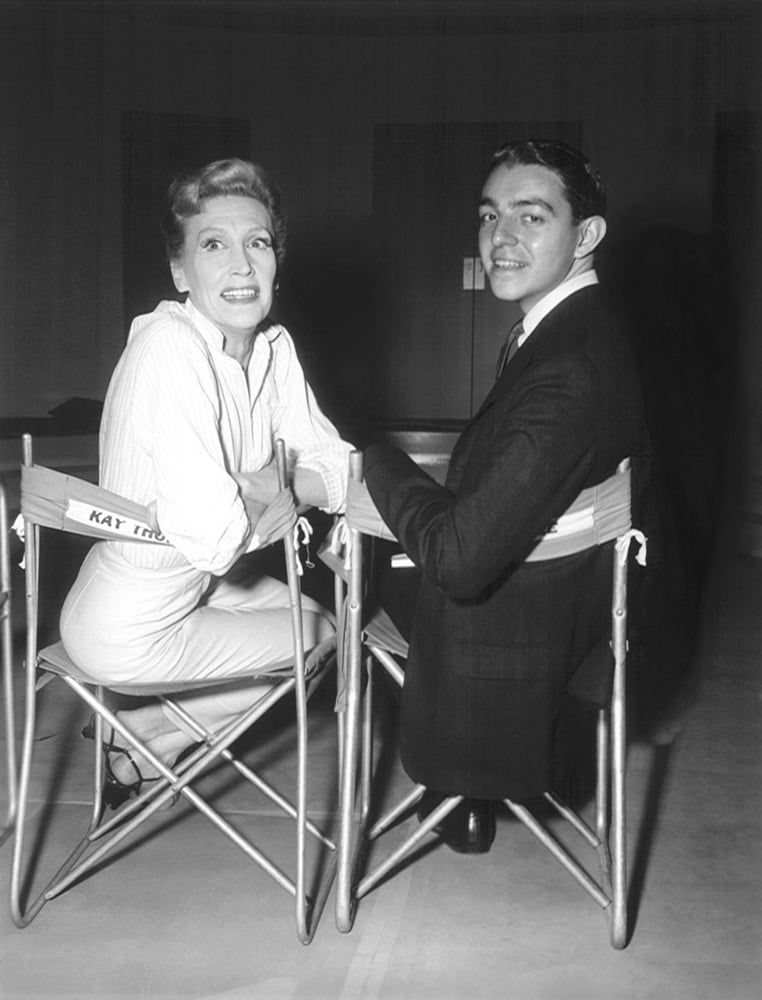

Unidentified photographer Kay Thompson and Hilary Knight on the set of Funny Face (1956). Courtesy of Sam Irvin.

There were challenges to mounting the exhibition; the original art from the first three books was lost in a flood at the Simon & Schuster offices. Perhaps partly as a result, the exhibition is relatively small—half of the final gallery serves as a gift shop—but the highlights are undeniable.

Spared from destruction were the original drawings from Eloise in Moscow, which Knight and Thompson produced after visiting the Soviet Union. Each illustration features a Soviet spy following around the title character. (Knight later expanded on the hidden character conceit in 1964’s Where’s Wallace, which predates Martin Handford’s better-known Where’s Waldo? by more than 20 years.)

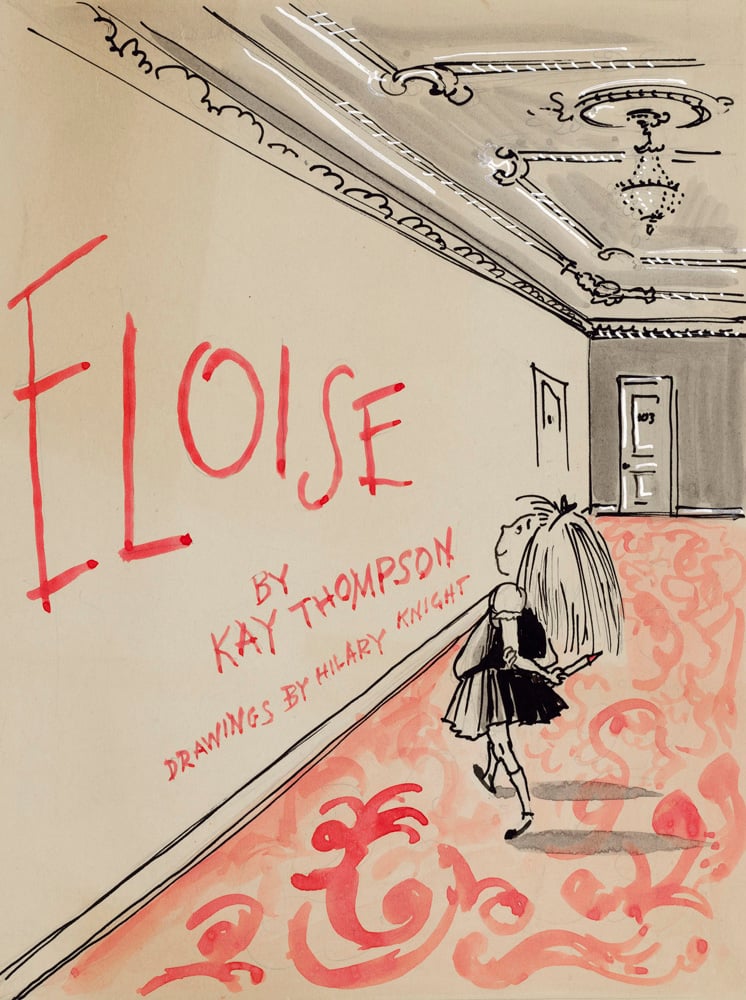

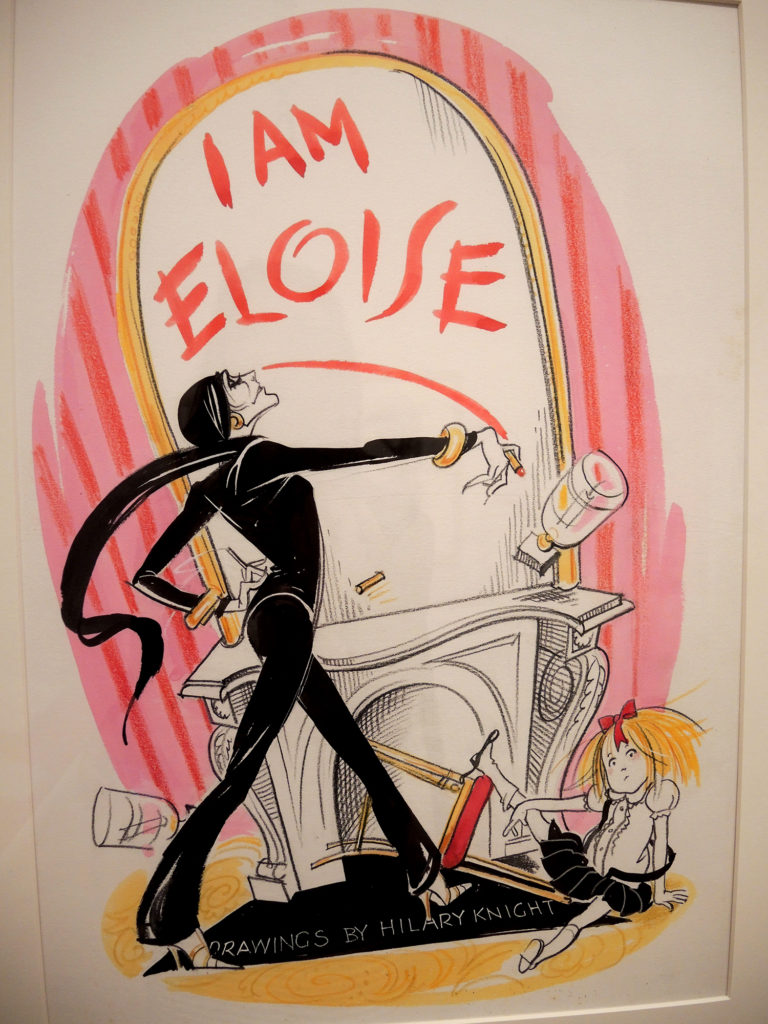

Hilary Knight, Unused cover sketch (1954) for Eloise, Simon & Schuster (1955). Collection of Hilary Knight, © Kay Thompson.

Thompson’s handwritten manuscript is there, along with early character sketches by Knight. A recreation of Eloise’s bedroom features bookshelves full of Knight’s later publications, including Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle. There’s also a copy of his unpublished children’s book with Truman Capote, Can a Pig Fly? On Thompson’s side, there are photos from her memorable turn opposite Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire in Funny Face, and a recording of her “Eloise” theme song, a Top 40 hit in 1956.

Notably, the show marks the first public appearance in 57 years of the original Eloise painting that hung in the Plaza Hotel. In 1956, knowing that Thompson was about to be interviewed on TV about Eloise, Knight quickly painted the piece and gave it to her as a birthday gift. The piece made it on air.

The painting hung at the Plaza for four years, until it was stolen in 1960. Walter Cronkite broke the story of the “kidnapping” on CBS Evening News, but the highly publicized theft went unsolved for two years, until an anonymous caller tipped Knight off that the painting was in the trash on 84th Street.

A recreation of Eloise’s bedroom at “Eloise at the Museum” at the New-York Historical Society. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

The artist recovered the work, but it was severely damaged by the ordeal, crumpled up and partly torn to shreds. Devastated, Knight packed it away in a closet, where it remained until Curley began working on the show. (The Eloise painting at the Plaza today is a replacement Knight created at the hotel’s behest in 1963, and is sturdier than the dashed-off original, on flimsy paper.)

“It took months to find,” recalled Curley. “It was in the back of the linen closet tucked in among the vintage Christmas wrapping papers.”

To look at it, you would never know what the painting’s been through—a testament to the prowess of the conservators—but an illuminating video next to the piece shows the challenging repair process carried out on the delicate tempera-on-paper piece.

Hilary Knight, final illustration for I always stay at the National whenever I am in Moscow (1959) for Eloise in Moscow, Simon & Schuster (1959). Collection of Hilary Knight, © Kay Thompson.

Though Eloise remains an enduring figure in pop culture, the series’ initial run was short-lived, ending in 1959 with Eloise in Moscow. The exhibition reveals that Eloise is in some ways a child of divorce, not in the books, where the character’s parents go unmentioned (although their reconciliation was the plot of the critically slammed 1956 television movie version), but in real life. The deteriorating relationship between Knight and Thompson led to the end of the series after critics panned the words but praised the pictures for the final book.

Among other likely contributing factors were the rising popularity of Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, published in 1957, and the introduction of Mattel’s Barbie doll in 1959. Whatever the reason, Thompson refused to finish the fifth book in the series, Eloise Takes a Bawth, and pulled the three existing sequels from publication.

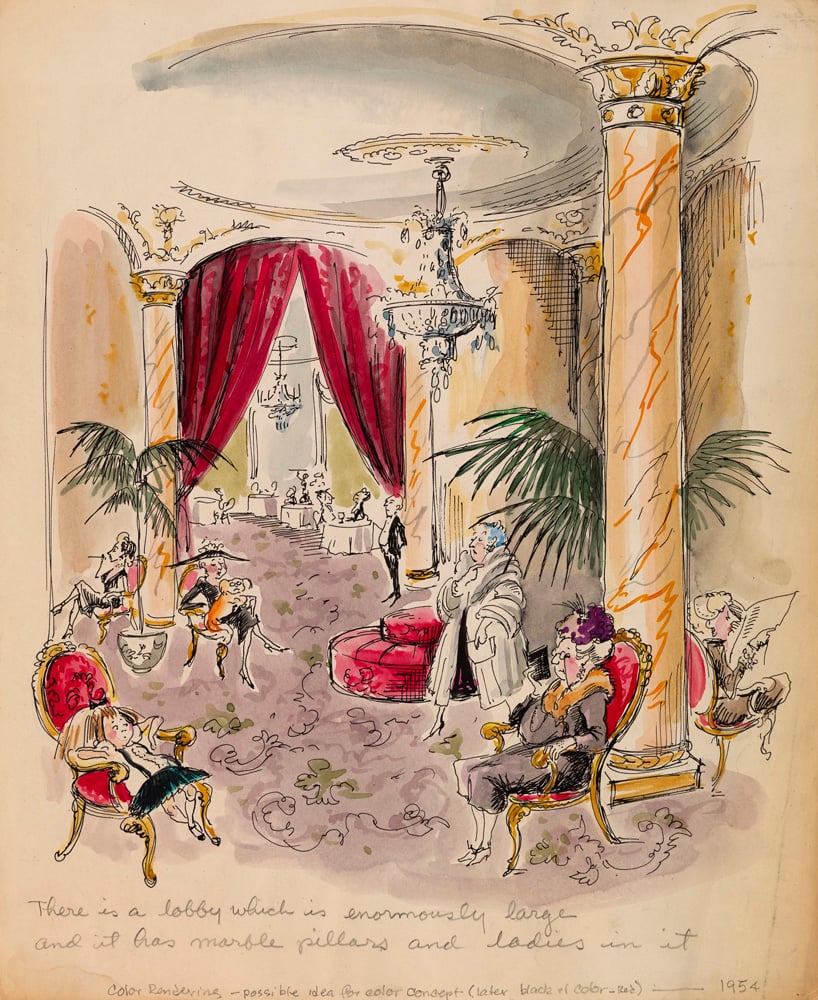

Hilary Knight, Unpublished color concept rendering for There is a lobby which is enormously large . . . (circa 1954) for Eloise, Simon & Schuster (1955). Collection of Hilary Knight, © Kay Thompson.

In light of Thompson’s disenchantment, the timing of the theft of the Eloise painting becomes somewhat suspicious, leading her one-time partner to speculate that perhaps she staged the crime. “She was the mistress of the publicity stunt,” said Curley. “She was over and done with Eloise, and I think this was Eloise making her grand exit. That’s my theory!”

The exhibition wall text suggests that if Thompson did steal and destroy the painting, doing so was a way to assert the primacy of the author’s voice. If Thompson was jealous, perhaps it was because Eloise was no longer hers and hers alone.

Hilary Knight drew this drawing of Kay Thompson and her character Eloise, hinting at the author’s inability to share credit for her beloved creation. It is on view at “Eloise at the Museum” at the New-York Historical Society. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

Knight’s spirited illustrations were part and parcel of the character’s success, and his designs were his own, deeply personal creation. When asked to draw the little girl, his mind immediately went to a painting by his mother, Katherine Sturges Knight. (His father, Clayton Knight, was also an artist.)

“I grew up with this. This is the actual inspiration for Eloise,” said Knight at the press preview, pointing to the small painting of a girl sitting in a chair. “It expresses the attitude and the extreme sense of fashion Eloise inherited.”

Hilary Knight was inspired by this piece by his mother, Katherine Sturges Knight, in his design for Eloise. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

The color of the scheme comes from his childhood as well, inspired by a New Yorker cover his parents designed together. A hand-painted copy by Knight is among the works in the exhibition.

What you also might not know is that Eloise was never intended to be a children’s book. “Thompson really did not like children, was not writing for children, was pissed off that children liked Eloise,” explained Curley. “She would go into Doubleday’s on Fifth Avenue and sweep up armfuls of the book out of the juvenile section and march them over to the adult section.”

Eventually, Thompson realized how profitable merchandise for the series could be and relented, releasing lines of Eloise-themed toys. In addition to one of the original dolls made in 1957 by Hol-Le Toys, which went bankrupt when it couldn’t match customer demand, the museum has managed to get its hands on one of four larger-than-life versions, produced as prototypes.

The original Eloise doll from Hol-le Toys, and one of the four prototypes for an unproduced life-size version on view in “Eloise at the Museum” at the New-York Historical Society. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

For anyone who grew up reading about Eloise’s exploits, the exhibition will be full of nostalgia—even the illustrator isn’t immune. “To be with stuff that you did 60 years ago…” marveled Knight. “It looks just the same, like I did it last week!”

“She’s such a New York girl,” said Curley of Eloise. “She’s a role model for anyone who is feisty and has an imagination and wanted to do what she wants to do!”

“Eloise at the Museum” is on view at the New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West at Richard Gilder Way (West 77th Street), June 23–October 9, 2017.