Art & Exhibitions

New-York Historical Society Fêtes Ludwig Bemelmans’s Plucky French Heroine

The book's earliest draft was written on a New York restaurant menu.

The book's earliest draft was written on a New York restaurant menu.

Sarah Cascone

Madeline, the classic children’s book series about a plucky little French girl’s adventures at boarding school, turns 75 this year, and the New-York Historical Society is marking the anniversary with “Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans.”

The exhibition brings to light more than 90 paintings, photos, comic strips, ceramics, and drawings by the self-taught illustrator, revealing a fascinating career that extended well beyond children’s books. Bemelmans’s true artistry is immediately apparent, and his feisty heroine, named for his wife, Madeleine, just may capture your heart all over again. (He dropped the extra “e” because he thought the “line” sound would lend itself to easier rhymes.)

She might just be world’s most famous Frenchwoman, but “Madeline was born here in New York,” curator Jane Bayard Curley assured visitors during last week’s press preview. Bemelmans, who moved to New York from Germany 100 years ago, at age 16, wrote his earliest draft of his most famous book on the back of the menu at the still-extant Pete’s Tavern on Irving Place.

Installation of “Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans.”

Photo: Leeanne Carroll, courtesy the New-York Historical Society.

A classic “bad boy” (according to Curley), Bemelmans struggled in school as a child, and was apprenticed to a hotel at age 12. That came in handy when he moved to the States—after a spot of trouble with the law, it was America or reform school—and was immediately hired by the Ritz Hotel.

Art didn’t come into the picture until after Bemelmans served in World War I. He suffered a mental breakdown, and it was learning to draw that got him through it. “Drawing saved him,” said Curley.

Bemelmans started out as a cartoonist for New York World in 1926, but got his big break when Viking Press editor May Massee stopped by his studio and recognized his potential as a children’s book author. Though Massee would later misguidedly pass on Madeline, it was her keen eye that helped Bemelmans’s career take off.

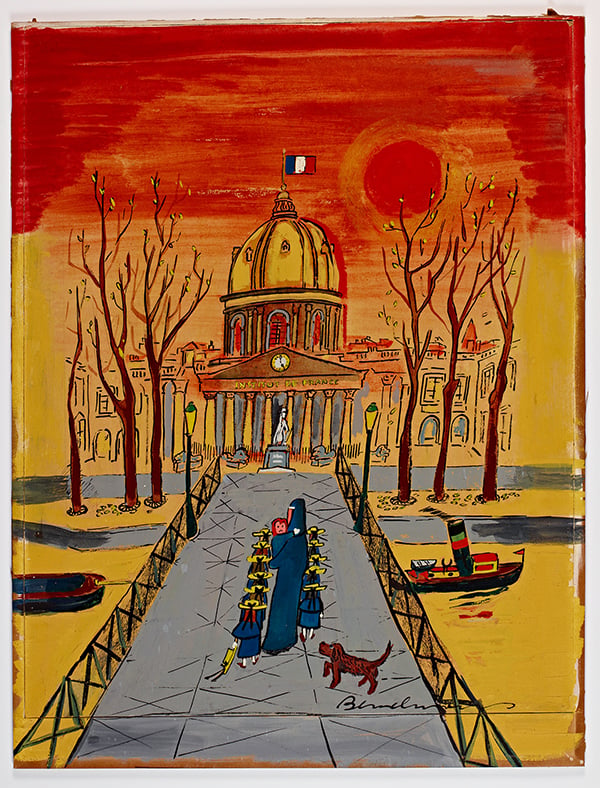

Ludwig Bemelmans, cover for Madeline’s Rescue (1953).

Photo: Courtesy the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Laurel D. Schumann Collection.

Of course, Madeline, which Curley described as essentially “a European immigrant recreating a Parisian fantasy,” became wildly popular, especially as the real Paris suffered through the Second World War. On view at the New-York Historical Society is the original manuscript for the book, as well as preparatory drawings, and a copy of an earlier book, The Golden Basket, which featured Madeline in a supporting role.

The show also reveals Bemelmans’s friendship with former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who wrote a fan letter telling the author how much her children enjoyed his stories, and jokingly scolding him for planting dangerous ideas in her daughter Caroline’s head, like jumping into the Potomac River. The exhibition includes the artist’s original correspondence with the first lady, some formal invitations, and early drafts for a book chronicling Madeline’s visit to the White House (an idea finally realized by Bemelmans’s grandson, John Bemelmans Marciano, who has written and illustrated several Madeline books of his own).

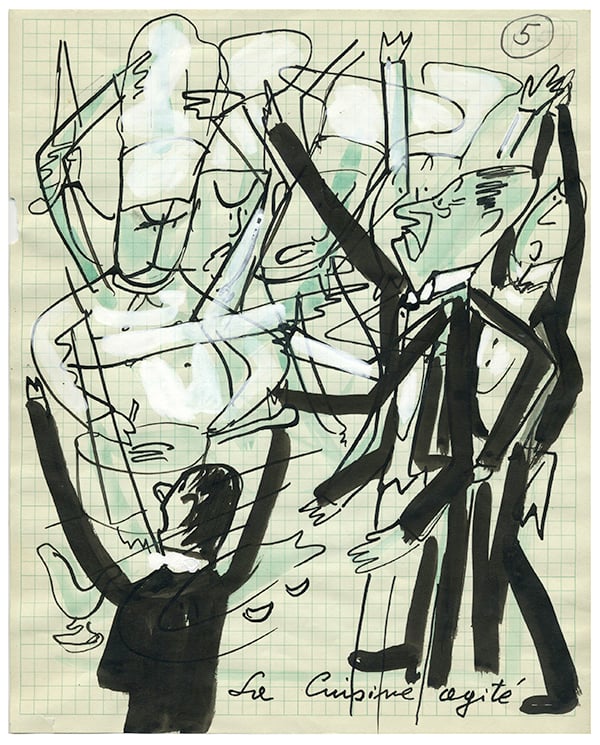

Ludwig Bemelmans, “Even Miss Clavel said” (circa 1956/57), from Madeline and the Bad Hat.

Photo: Courtesy Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce.

Of particular note are several panels salvaged from Aristotle Onassis’s yacht, the Christina, which featured a children’s playroom decorated with 15 scenes from Madeline painted by Bemelmans. The paintings were nearly lost when the decaying ship was purchased for a pittance in the 1980s, Curley told artnet News, but a chance appraisal led to the paintings’ sale, which raised enough money to restore the yacht.

According to Curley, the story shares a striking symmetry with an episode in Bemelmans’s own life, in which he bought a wrecked Hispano Suiza car with leopard print seats from a grieving Spanish nobleman whose mistress had died in the crash. The artist didn’t have the money to fix it up, until he found the late mistress’s diamond-encrusted gold cigarette case in the glove compartment.

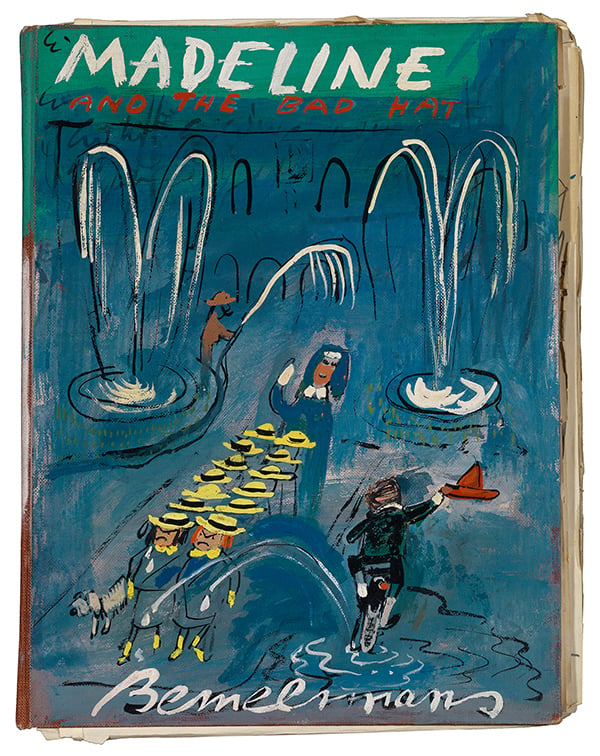

Ludwig Bemelmans, dummy cover for Madeline and the Bad Hat (circa 1956/57).

Photo: Courtesy the estate of Ludwig Bemelmans.

While he is best known for his books, Bemelmans’s artistic pursuits were wide-ranging, partially because he needed the money. In addition to comics, the artist illustrated menus and advertisements for restaurants, worked on the screenplay for a Fred Astaire movie, helped write a never-produced Frank Sinatra play, and even authored a photo book encouraging young people to work in the hotel industry.

Examples of many of these projects are included in the exhibition, plus hand-painted Madeline plates, a newspaper Jell-O advertisement with the coupon thriftily snipped out long ago, and printed fabric swatches commissioned by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. As interesting and unexpected as these oddities are, the showstoppers are the Madeline paintings, gorgeous oil, gouache, and watercolor works that bring iconic scenes from the series to life in a way that a mass-produced book with mostly two-toned illustrations never could.

During his lifetime, Bemelmans sold these finished versions of his illustrations at Hammer Galleries in New York City. According to Curley, dealer Victor Hammer once caught the artist using some sketches to kindle a fire, and had to reprimand him for burning what was essentially currency.

Many of the works in the show, including several murals salvaged from the artist’s short-lived Parisian bistro, La Colombe, are from the collection of Chuck and Deborah Royce, who have turned Ocean House, a luxury resort in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, into a mini-museum of illustration, with a particular focus on Bemelmans. They began collecting the artist’s work after a chance viewing in the Bergdorf windows of Bemelmans’s comics remembering life at the Ritz commissioned by Town & Country on the occasion of the hotel’s closing.

Ludwig Bemelmans, “Interesting as the hotel was, my ambition was to paint” (1950), from “Adieu to the Old Ritz” in the December 1950 issue of Town & Country.

Photo: Courtesy Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce.

Those witty, slice-of-life drawings are a highlight of the show, offering a window into a bygone era of high-end New York hotels and showcasing Bemelmans’s ability to deftly capture bold personalities in a few simple lines. Especially amusing is the story of the hotel porter Amadou, whom Bemelmans hired as a chauffeur and outfitted in a special uniform, only to discover that the man couldn’t drive. Such anecdotes, and the show as a whole, bear testament to Bemelmans’s larger-than-life personality and add texture to his bold, precocious Madeline.

“Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans” will be on view at the New York-Historical Society through Oct. 19, and will then travel to the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, which organized the exhibition.