Art World

Emma Sulkowicz Explains Her Provocative New Bondage-Based Performance Art

Emma Sulkowicz's next project will be an art sex dungeon.

Emma Sulkowicz's next project will be an art sex dungeon.

Sarah Cascone

Two years after graduating from New York’s Columbia University and completing her much-covered, year-long endurance-based Mattress Performance, artist Emma Sulkowicz is causing an uproar once again.

She inadvertently became one of the faces of the movement against rape culture on college campuses with her Columbia thesis project, which saw her carry a dorm mattress around campus in protest in the school’s handling of her sexual assault complaint. It also earned Sulkowicz her fair share of critics, who question both her motives and her accounts of her assault.

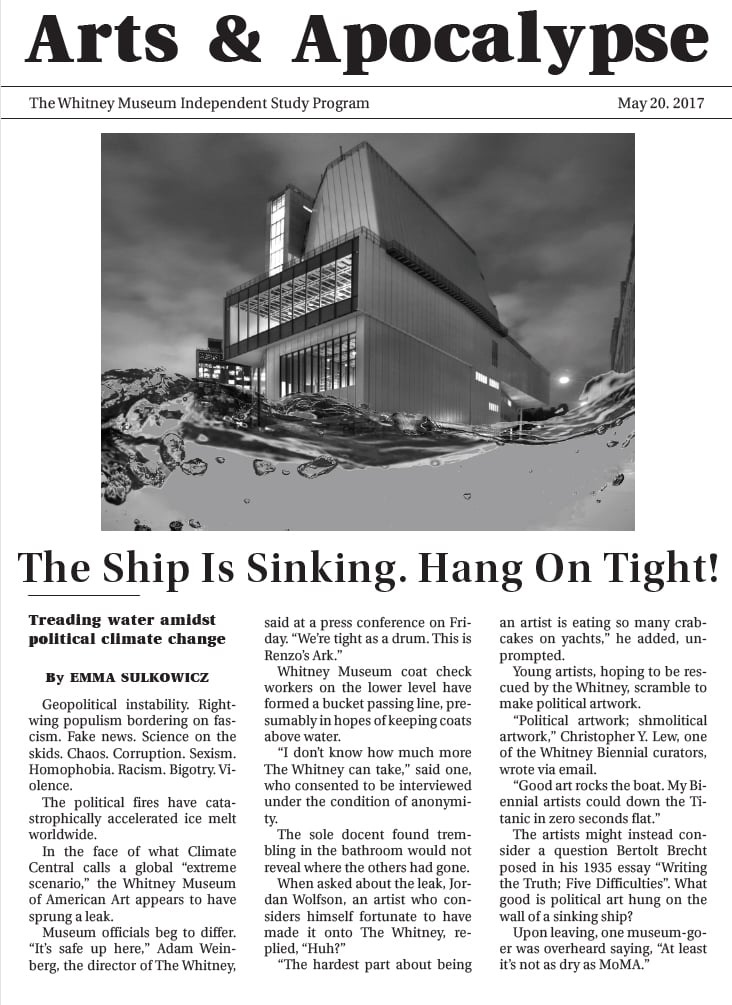

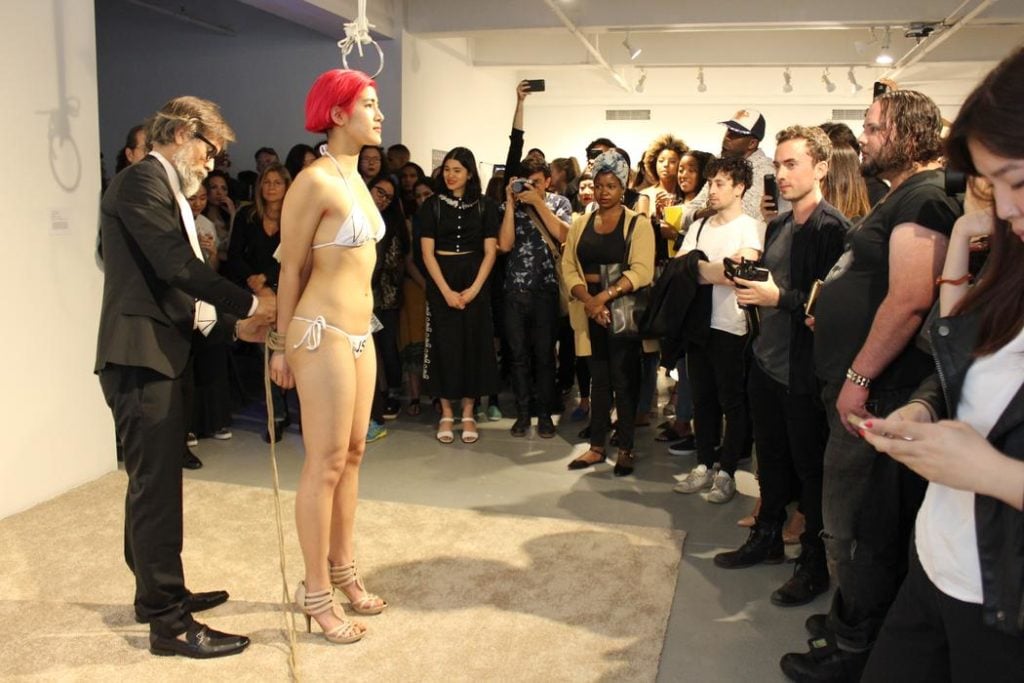

Sulkowicz’s new work almost seems to be crafted specifically to troll her critics. For the new piece, titled The Ship Is Sinking, she wore a white bikini adorned with the Whitney logo. An S&M professional who goes by “Master Avery,” playing a character called “Mr. Whitney,” bound Sulkowicz tightly and hung her from the ceiling on a wooden beam, periodically whipping and insulting her.

As Sulkowicz explains below, the piece was meant as a multilayered exploration of ideas surrounding sex and consent, societal standards of female beauty, the personal nature of making and sharing art, and the art world in the age of Donald Trump.

The May 20 performance was her final project for the Whitney Independent Study Program (ISP), and was part of the program’s studio exhibition. The show is on view at New York’s Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts through June 3—though if you stop by you’ll see no evidence of Sulkowicz’s work.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Ship Is Sinking. Courtesy of Emma Sulkowicz.

The title of the The Ship Is Sinking was inspired by Bertolt Brecht, who wrote “They are like a painter adorning the walls of a sinking ship with a still life.” (In preparation for the piece, Sulkowicz even drafted a news article in which the Whitney Museum of American Art was sinking, presented as a handout at the show, depicting the museum as a literal sinking ship.)

We talked at length about the piece, her evolution as an artist, her plans to open an art sex dungeon, and how the often deeply personal attacks of internet commentors actually inform and strengthen her work.

Emma Sulkowicz’s The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Leila Ettachfini.

Why did you respond so strongly to this idea of art on a sinking ship, and the art world going down with the ship?

I love that image. Brecht’s talking about a disintegrating country, and I was like that’s really applicable to us today with Donald Trump.

On every sinking ship there actually is a female body strapped to the front of the ship, and I realized that I could embody this. The image in my head was kind of a cross between a figurehead on a ship and a witch tied to the stake at a witch trial. I really liked the idea that witches are hated—that’s the whole point.

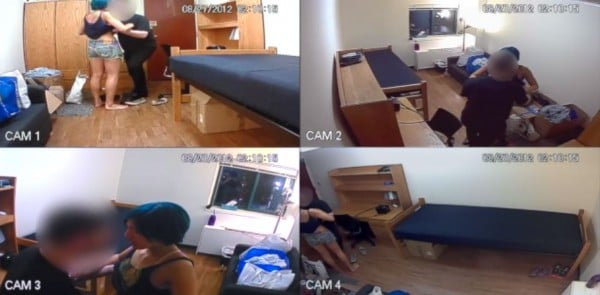

Still from the video titled Ceci n’est pas du viol by Emma Sulkowicz.

You did Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, a video that appears to recreate your alleged rape, knowing that people would respond and say really hurtful things about you. You’ve been following along as people have continued to post nasty comments. Do you find that kind of negative feedback is productive for you?

In the beginning of The Ship Is Sinking I went up to Master Avery and was like “Mr. Whitney, I want to be an artist.” Before he started tying me up, he told me “your boobs are too small,” and “you’re not strong enough to be an artist.” He critiqued my body in the way commentors did after Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol.

It’s really interesting because on the one hand, I have hoards of trolls saying that I’m too fat, my butt isn’t big enough, my boobs aren’t big enough, and on the other hand you have people who are supposedly educated saying you’re too pretty. No matter what, my body’s not going to be good enough in the eyes of many people. The piece is meant to show all the kinds of ways that fem bodies are put down.

Do you ever worry about feeding the trolls? In a way, you’re pretty much doing exactly what they want you to do.

I think they want me to get into little squabbles in comment sections. What’s cool about taking the empowered stance of a witch at the stake is that the more hate I get, the more powerful of a witch I am.

Every insult that you could come come up with related to my body, I can just use to make my performance piece stronger. I’ve lately been thinking about this idea of empowerment from the position of dispossession. It is very witchy. All of your hatred is going to become a part of my spell.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Katia Repina.

Were you at all inspired by any of the witches against Donald Trump?

I wasn’t really following that. But one thing that people kind of notice when they see the piece is, “huh, a figure head normally wears kind of flowy robes.” I considered a kind see-through flowy robe for the piece. But for some reason I kept seeing it in my mind as this kind of ridiculous thong bikini with sparkly heels.

I realized it was because of beauty pageants and Trump’s history with them. Also, when I made Mattress Performance, I didn’t know shit about the art world or that there was an art world or anything like that. Now that I’ve seen it a bit more, I realize that there’s so much pageantry. Everyone’s trying to outperform each other—the question is, to impress whom.

I decided to go with that impulse to copy a beauty pageant, and get really detailed with it. I did the bikini. In beauty pageants you’re supposed to wear nude heels with tasteful amounts of glitter—I went a little overkill on that—and I even got a French manicure/pedicure. I went all out.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Leila Ettachfini.

For your performance, the backstory about the art world sinking and the sinking ship doesn’t really come through as much as the idea of what you are willing to endure for your art. How do you see those two elements as tying together?

I’m telling you all the stuff that inspired this in the first place, but of course by the time the performance happens, it’s a completely different monster. For me, what that performance ended up being is about how artists are expected to show pain all the time.

A lot of us are expected to express pain through our artwork, and people consume it, like if a person makes a painting about their dad who died, or a person takes photos of the sickness they have. The whole conceit was that I was saying “Mr. Whitney, I want to be an artist,” and he was like “Oh yeah? let’s see if you can take it.” And the idea was that I was going to stay up as long as I could, until I couldn’t take the pain anymore, and then I would come down.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Katia Repina.

We had a 15 minute break, and then I approached him again, I put the wood up myself that time, and I approached him and said, “Alright, I know what it takes to be an artist, I am ready.” And he tied me up again, but this time it was a lot more painful, and he invited audience members to join in. And somebody actually went for it! I thought that was great because then you have that whole thing that artists are suffering pain at the hands of the audience too.

Did he talk to you after?

If you look really closely in the video, there’s a moment where he’s looking to me to see that it’s okay, and I nodded. There’s a little moment of getting consent. After, he was like “wow, I really love your art.”

One of my friends asked me during the break how long I would have to stay up there to be an artist. I was like, “I mean, forever, right?” You have to endure infinite pain to be an artist.

Emma Sulkowicz’s The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Leila Ettachfini.

Was it as painful as it looks?

I still have some bruises, honestly! They’re still healing.

The second time was so painful. But the energy from the audience—the gallery shut the lights off, because they wanted us all to leave, but everyone in the audience lit up the stage with their phones’ flashlights. The audience wanted it to keep going so at that point I was in such a performance mindset that I actually could have taken anything. I actually could have stayed up forever, I was so in the mental zone. But at a certain point I had to come down!

In college, did you have any serious aspirations of being a performance artist?

No! When I did Mattress Performance, I didn’t even really think of myself as a performance artist. I was like oh I’m going to do a piece in which I perform. And then maybe I’ll do a sculpture, or a photo. But each performance gave me the idea for the next performance, and it’s just been this kind of natural thing.

Emma Sulkowicz, a senior visual arts student at Columbia University, carries a mattress in protest of the university’s lack of action after she reported being raped during her sophomore year on September 5, 2014 in New York City. Courtesy of Andrew Burton/Getty Images.

In your work now, it seems like you like to have intellectual underpinnings that maybe don’t even come through in the finished piece. Was there a lot of theory behind Mattress Performance, or was it more that you realized you had kind of unwittingly tapped into a deeper history of performance, and having done that so successfully inadvertently did that make it a more important aspect of your work moving forward?

That’s another thing that inspired me with this performance. You had a lot of criticisms of the party piece that I did, and that was also not a piece that I was happy with.

I was in the ISP, and we read so much theory, and it’s bone-fucking dry. At the end of Walter Benjamin’s “Art in the Age of Technological Reproducability” essay, he basically says that aesthetics are categorically bad. I just kind of feel like that kind of shit was influencing me when I made that party piece. I was like “yeah, I’m going to make it like anti-aesthetic”—terrible.

I wanted to make The Ship Is Sinking a piece that people would be engrossed in. I wanted it to be something that people would be interested in looking at. I felt almost this pressing need to return to making something aesthetic.

Mattress Performance, as you noted, came out of zero theory. Then I read a ton of theory and I got really in my head, and I kind of needed to be snapped out out of it. Theories are important and I can use it to explain my shit to people, but at the end of the day it has to be something that’s coming from the gut. I wanted to say thank you for fucking snapping me out of that because I needed it!

The Ship Is Sinking was painful, but it was so much fun for me to make. Every second of it I was excited. I was excited about art making again.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Healing Touch Integral Wellness Center. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Contemporary/Emily Belshaw.

Some of the criticism of The Ship Is Sinking has centered around how you’ve gone back to more sexual work, supposedly because your piece at the Philadelphia Contemporary didn’t get you the attention you wanted—

They know me so well!

Those kind of accusations of being an attention-seeking whore, those were those same things that I was trying to build into the piece. Numerous times throughout the performance Master Avery as Mr. Whitney would say “how’s that for attention? You want attention?” and hit me.

When a rape victim comes forward and everyone says she’s just seeking attention, it’s like “what kind of fucking attention do you think this rape survivor wants?” A bunch of trolls sending her rape threats? You’re very mistaken. So I paired these accusations of me wanting attention with me being hit to show that when people accuse me of being attention seeking, they are the ones who are abusing me.

What would you say to critics who say that this is not empowering, the sort of “what would you say if this was your daughter?”

My parents were stoked about this piece! [Laughter]

But there’s something that I think goes back to how women are “supposed” to present themselves in society. Obviously the piece was intended to show you being willing to debase yourself, but do do you feel that you’re reclaiming that action, or actually…

I was debased? I think this is where authorship is really important.

One of my friends was in the audience and was next to two art students who didn’t know that I was the artist and were coming at it with a cold read. They were like, “ok, what we see here is a woman being tortured by a man. If this artwork is by the man, we are going to be so fucking pissed off. If it’s by the woman, we are totally okay with it and we see how it’s empowering.” My friend told them I was the artist, and they were like “thank God.”

That’s the difference. I was the one calling the shots. I told Avery which kinds of torture I was okay with.

Lately I’ve been reading this book Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty by Gilles Deleuze. He talks about how [the Marquis de] Sade has a whole system of sadism, and [Leopold von Sacher-]Masoch has a whole system of masochism, and they’re very separate. The perfect sadist is this man who finds unwilling victims and rapes and tortures him. In Masoch’s system it’s about a man finding a woman who’s willing to torture him, so it’s actually consensual.

Emma Sulkowicz, The Ship Is Sinking (2017). Photo by Katia Repina.

So where the sadistic system is patriarchal, the masochistic system is actually matriarchal. It’s really easy to jump on board with the masochistic system, but the protagonist is still the man. What about a consensual system with a female protagonist? It would look the same as a sadistic system, like a man torturing a woman, but it would be based on consent.

For Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, I had to come up with a contract with the actor to make something that looks like rape, but is actually consensual. So I have been thinking about this for awhile.

I think that people do have violent urges, it’s just a part of living. How are you going to express those violent urges? You can do it the sadistic way in which you find unwilling victims and torture them, or you can find consent, find a person who’s willing to play these things out with you. And then you can have violence that’s completely consensual.

I feel like if rapists knew there were consensual ways to satisfy their violent cravings, who knows, right? That made me feel like there is a political impetus to talk more openly about consensual kink.

There is a lot of educational work to do. This summer, I think my best friend and I are going to start an art sex dungeon, where we can educate people on consent and consensual kink.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

See video documentation from Emma Sulkowicz’s performance art piece, The Ship Is Sinking.