Art World

Eureka: The Deep Symbolism Behind Gerhard Richter’s Candles

The contemporary artist's photorealistic images of candles emerge from his desire to break free from reality and bias.

At a glance, Gerhard Richter’s images of candles look like blurred photographs. In truth, they are meticulously crafted paintings that manage to recreate the effect of a camera shooting its subject slightly out of focus. Richter’s candles—one of which, titled Kerze, sold in 2011 for more than $13 million—hover between reality and illusion, objectivity and subjectivity, not unlike how the artist spent his youth in East Germany, wedged between capitalist Europe and communist Russia.

Richter, now one of the most successful contemporary artists on the planet, commanding retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art and Tate Modern, was born in 1932 in Dresden, seven years before the start of World War II. He started drawing at age 15, attending art school in East Germany, where his training was steeped in Socialist Realism, a representative art movement that promoted the ideology of the Communist Party.

The painting Kerze mit Schaedel (Candle with skull) by Gerhard Richter is hung up at the arts hall in Rostock, Germany, 2011. Photo: Jens Buttner / DPA / AFP via Getty Images.

Although his early projects—including a mural for the Deutsches Hygienemuseum—were well-received, Richter found himself dissatisfied with Socialist Realism, which he felt stifled artists’ creativity. Equally critical of capitalism and consumerism, he spent his adolescence looking or what Contemporary Art Issue calls a “third way.”

Such a way opened up for him when, after moving to West Germany with his wife, Richter encountered the abstract work of Jackson Pollock and Lucio Fontana, and befriended German painters Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo, and Konrad Fischer. Turning the judgmental lens of Socialist Realism onto Western society, Richter produced paintings and photographs that commented on media, current affairs, and popular culture, with televisions, advertisements, and politicians emerging as some of his favorite subjects.

Blurring the lines between his two mediums, Richter moved away from abstraction and began creating photorealistic paintings. He wanted to achieve with a brush what he was already able to do with a camera: to capture reality as is, free of historical or personal bias. Two new favorite subjects emerged, both inspired by 16th- and 17th-century vanitas paintings, still lifes with a moral subtext: skulls and candles.

Candles have come to occupy an especially important place in Richter’s oeuvre, with fellow German artist and art historian Hubertus Butin going as far to say “no still-life motif has been such an object of fascination.”

As Richter himself explained in a collection of writings, interviews, and letters: “Candles had always been an important symbol for [East Germany], as a silent protest against the regime… it was a strange feeling to see that a small picture of candles was turning into something completely different, something that I had never intended. Because, as I was painting it, it neither had this unequivocal meaning nor was it intended to be anything like a street picture. It sort of ran away from me and became something over which I no longer had control.

While conflict wasn’t on his mind while he painted his candles, the artist said, “I did experience feelings to do with contemplation, remembering, silence, and death.”

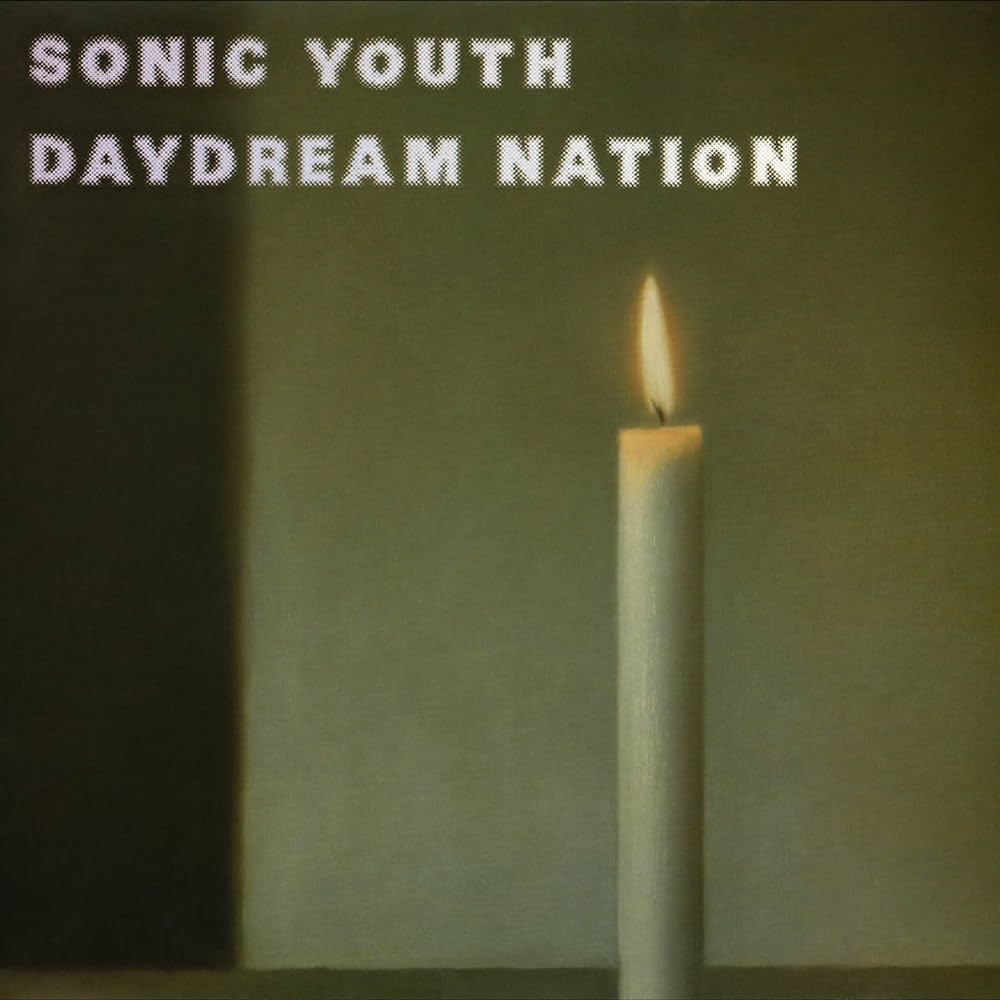

Sonic Youth, Daydream Nation (1988), featuring a painting of a candle by Gerhard Richter. Photo: Goofin Records.

And the enduring popularity of Richter’s candle paintings may be partially attributed to a 1988 partnership with the American band Sonic Youth, who used a 1983 painting as the cover for their album Daydream Nation. Since then, the flame has never dimmed.

What inspired Mary Cassatt‘s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists‘ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.