Artists

‘The Rainbow Is a Bridge:’ How Ugo Rondinone Imbues Outer Landscapes With Inner Worlds

The artist opens up in a rare interview on the occasion of his landmark retrospective in Switzerland.

Ugo Rondinone’s triumphant thirty-year retrospective at the Kunstmuseum Luzern is an ode to Switzerland’s majestic overlapping mountains and verdant terrain. “Cry Me a River” ranges from his early to most current work, reflecting themes that have been a consistent inspiration. The same reverence for nature that inspired his 1990s large-scale black and white landscape drawings also animates his very popular Seven Magic Mountains, the dayglow rock formations that have graced the Nevada desert since 2016.

Born in Brunnen, Switzerland, to Italian immigrants from the ancient town of Matera, the Swiss multidisciplinary artist is internationally renowned for his oeuvre that synchronizes contemporary experience with primal origins. As the artist turns 60, this retrospective feels like a homecoming, and “takes us on journey into the artistic universe he has created,” Rondinone’s gallerist Eva Presenhuber said in a statement.

Portrait of Ugo Rodinone in his studio by Elvin Tavarez.

This spring I first viewed “Cry Me a River” in the artist’s central Harlem studio. A New Yorker for decades, he lives and works in a renovated church, replete with spring ceilings and original stained-glass windows. In a rare interview, Rondinone detailed each room of his upcoming show, rendered in miniature modeled perfection.

The exhibition’s title comes from the famous American torch song originally composed by Arthur Hamilton in 1953, and is one he has returned to over the years. It speaks to the River Reuss in front of the Kunstmuseum, which flows from Lake Lucerne, near where the artist grew up, and perhaps also references New York’s Hudson River, blocks from the the artist’s studio.

Three months later, I journeyed from Italy to Lucerne for the Kunstmuseum opening. Designed by French starchitect Jean Nouvel, the dazzling waterfront building is on the shores of pristine River Reuss and steps from the modern train station. Housed on the spacious glass walled fourth floor, the Kunstmuseum’s permanent collection encompasses 500 years of Swiss art.

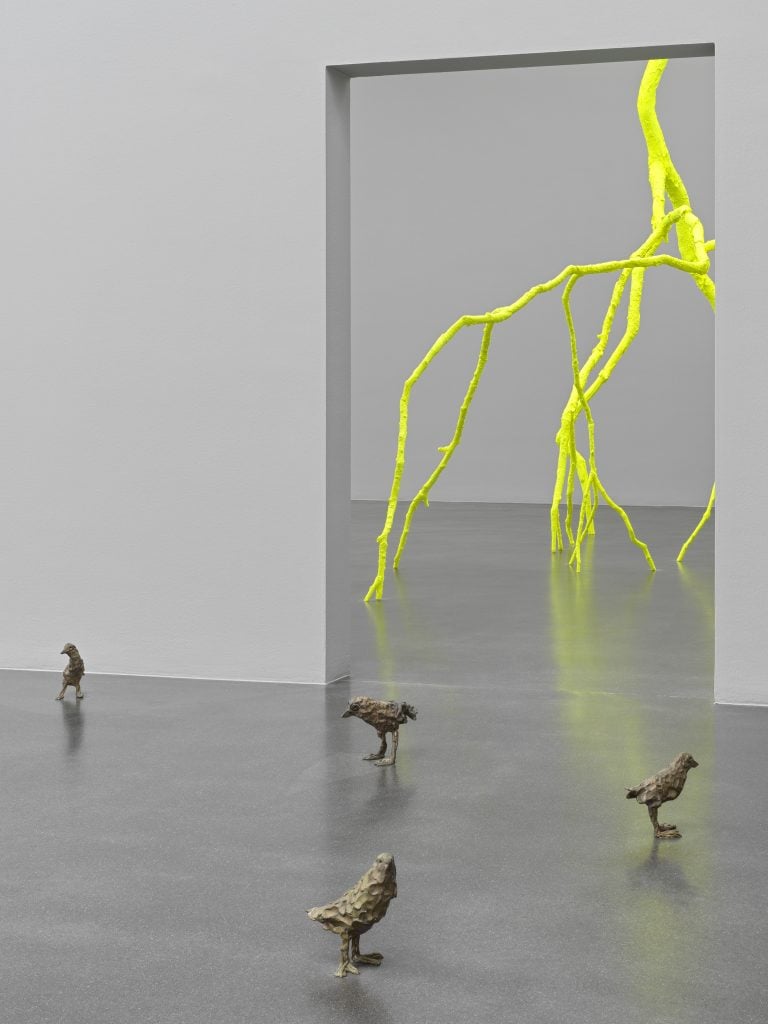

A consummate storm of large-scale bronze lightning bolts, painted a fluorescent yellow, commandeers the first room. These were first shown at the Gladstone Gallery in Chelsea, but here in Switzerland the dangerous beauty of the lightning group seems to await a zigzag electric flash. The ephemeral bolts are transmuted by the bright artificial color, bearing titles like Glorious Light and Luminous Light.

Installation view, Ugo Rondinone “Cry Me a River,” 2024. Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber.

Propped against a wall in the room, the show’s titular work is a 1995 sculptural self-portrait of polyester, hair and cotton, capturing the artist in repose. Barefoot, eyes cast down, cry me a river portrays Rondinone in a moment of youthful wistfulness.

In New York, the artist described it: “cry me a river from 1995 is the first of three mannequins of myself. A sitting figure in an otherwise empty gallery space. Later that year and the following year, I made a mannequin of myself lying on the floor, and another, leaning against a wall.” The early self portrait is the only representational human in the show, and reveals a rare moment of intimacy for the very private artist. At the opening, it took a moment for some people to notice the hyperrealistic, seated sculpture.

Portrait of Ugo Rodinone by Elvin Tavarez.

“The exhibition evolves throughout 11 successive rooms. Each room shows an artwork that represents the natural world—from the lightning in the first room to the snowfall in the last,” Rondinone said.” The self-portrait in turn generates a personal, meditative state throughout the exhibition, in which boundaries between the outside world and internally visualized space break down.”

In the catalogue essay, Marc Mayer, writer, director of Arsenal Contemporary in Tribeca, NY and former director of the National Gallery of Canada calls Rondinone “among the current scene’s most successful animists.” The inherent spirituality of the show also connects Rondinone to Innerschweizer Innerlichkeit, the famous “central Swiss interiority”—a curatorial term coined in 1968 to describe a stubborn, mystically inward characteristic of Swiss artists.

Installation view, Ugo Rondinone “Cry Me a River,” 2024. Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber.

The second room “Primitive,” is from 2011. A flock of 59 cast bronze birds perch on the floor, creating a winding avian pathway for viewers to step between them, some pecking the ground, others in alert stance. From the small birds to the gigantic stone figures, Rondinone investigates the duality and movement of sculpture. This theme energizes the entire exhibition, as the artist explores scale and mediums from traditional to technological.

Vertically slanted silver chains of rain (2004) replicate a downpour, crowned by a dark and threatening painted storm cloud. “Rain is an early work. Just chains and a sprayed silver cloud,” Rondinone offered a minimalist comment on the Zen-like shower of metal balanced by the overhead cumulonimbus.

Ugo Rondinone, Rain (2004). Photo: Ilka Scobie.

Five stone figures, from 2023, are part of the immense megalithic tribe I first encountered in New York City’s Rockefeller Center 2013 Public Art Fund exhibition. “I’m putting faith in stone as material, in its innate beauty and energy, its structural quality, its surface texture, and its ability to collect and condense time,” Rondinone has said.

The five bluestone humanoids are composed of five massive slabs, but the subtle differences of a geometric block head or a traditionally proportioned skull, rooted on powerful limbs give each figure a distinct energy. From the intimate birds to these massive figures, the artist toys with dimension while imbuing all of his pieces with a poetically restrained passion.

Ugo Rondinone, figures (2023). Photo: Stefan Alternburger. Courtesy of the Kunstmuseum Luzern (2024).

Midway through the show, we get some insight into Rondinone’s generous vision. He invited the children of Lucerne to create drawings for the show. Visions of the sun range from literal to abstract, all vibrant with the fresh immediacy of kids’ art. A special opening for the young artists has been held.

Elsewhere, 2016’s Primordial is a school of roughly textured fish suspended on wire. The fifty patinated bronze creatures speak back to the birds as part of a series of created between 2011 and 2016. “I made three groups of animal sculptures; birds, horses, fishes. Something from the air, the water, the earth,” Rondinone said. Each group was made up of 59 animals, each titled after a different natural phenomenon. As a group they are named, Primitive, Primordial, and Primal.

“I made the sculptures in clay. My fingerprints are covering the surface of the raw burned bronze. The sculptures are small and represent something bigger than us. My main interest is to show the intersection between the human and the natural world, as well as the limits of human consciousness in articulating such a meeting.”

Ugo Rondinone, your age, and my age and the age of the sun (2013–ongoing). Photo: Stefan Alternburger. Courtesy of the Kunstmuseum Luzern (2024).

In the final room, it is slowly snowing. In thank you silence (2005) a delicate pile of plastic flakes gathers on the gray wooden floor.

After the summer, the prodigious artist has upcoming European shows including Esther Schipper in Berlin, the Museum Würth in Germany, Reiffers Art Initiative and Mennour in Paris, and in December, will open at the Aspen Art Museum in Colorado.

My parting view of the show is the very first of the artist’s iconic rainbow signs, also called CRY ME A RIVER, from 1997. The neon, acrylic glass, translucent foil and aluminum signage illuminates the Kunstmuseum against the dark summer sky.

Ugo Rondinone, cry me a river (1997–2024). Photo: Stefan Alternburger. Courtesy of the artist and Kunstmuseum Luzern.

“The rainbow is a bridge between everyone and everything. The rainbow is a metaphor to our complex, ever-evolving attitudes toward the environment and human rights,” Rondinone said. “Nature is not something apart from us, but intrinsic. We must go beyond racial, ethnic, and religious identities to find a shared concern for the same ground that benefits human and nonhuman alike.”

Throughout the exhibition, Rondinone’s transcendental connection to nature touches on the sublime, referencing the concept of Innerschweizer Innerlichkeit. An incipient storm’s first raindrops, mammoth humanoids, a soundless snowfall, birds, horses, floating fish, all anchored by the mystery of a time defying clock. “Cry Me a River” is a career defining moment, as Ugo Rondinone continues elevating the quotidian to the cosmic.