Archaeology & History

Fragments of Previously ‘Lost’ Euripides Tragedies Have Been Translated

The discovery is among the most important in ancient Greek literature over the past 60 years.

In one of the most significant discoveries related to Ancient Greek literature over the past half century, archaeologists have uncovered around 100 lines from two otherwise lost plays by the 5th-century B.C.E. playwright Euripides.

The texts in question are Ino, a revenge tragedy of which 37 lines were discovered, and Polyidos, a moralistic tragedy of which 60 lines were uncovered.

The discovery came during excavations in late 2022 by an Egyptian team of archaeologists working at the ancient necropolis of Philadelphia, a site 75-miles southwest of Cairo. The papyrus was uncovered in 3rd-century C.E. pit graves connected to an older funerary structure.

The director of the Philadelphia excavation project, Basem Gehad, contacted Yvona Trnka-Amrhein, an assistant professor of classics at University of Colorado Boulder who he works with on excavations at Hermopolis Magna, an ancient city on the boundary between Lower and Upper Egypt. After establishing that the texts were Euripidean through an online database of ancient Greek texts, Trnka-Amrhein looped in her colleague John Gibert, an expert on Euripides.

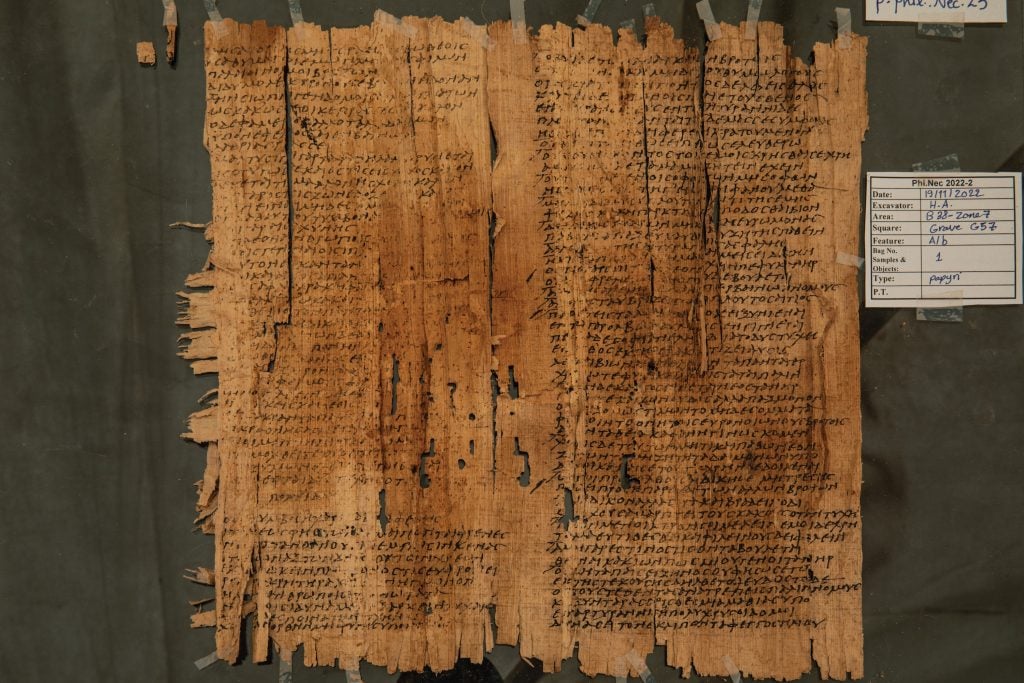

The site at the Egyptian necropolis of Philadelphia where the fragments were found. Photo: courtesy Basem Gehad.

Together, the academics have translated and analyzed the plays with their findings appearing in the latest edition of Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy, a publication with a focus on Greek and Roman literature, history, and philosophy.

“Ino and Polyidos, were known only by plot summaries and a handful of quotations before,” Trnka-Amrhein said via email. “This is the most significant find of Greek tragedy since the publication of a papyrus of Euripides Erechtheus in the Sorbonne collection in 1967.”

The papyrus has been dated to the 3rd century C.E. based on the writing style and the archaeological context in which it was found. The text breaks some words into their composite syllables, suggesting it may have been a manual of sorts for elementary readers. “The non-luxury format of the literary text preclude[s] commercial production,” the authors wrote, noting the producer of the book may have been a higher education teacher with a “well-stocked library of classics.”

Compiling key sections of celebrated texts was a fairly common practice, but one confusion for scholars was that the two plays do not represent a clear type, formally or thematically—though, intriguingly, given the site of their discovery, both texts prominently feature a tomb.

The papyri were found in a clump in the northeast corner of the tomb. Photo: courtesy Basem Gehad.

In the fragment of Polyidos, a myth in which King Minos pleads with the eponymous prophesier to revive his deceased son Glaucus, the two debate the nature of power, money, and good governance. “You’re rich, but don’t think you understand the rest. Ineptitude arises in prosperity,” Polyidos tells the king. “You are foolishly trying to overturn the established laws and throw the rules into confusion.” Previously, only a fragmentary plot summary was known.

In the fragment of Ino, a tragedy in which Ino and Themisto, the first and second wives of the Thessalian king Athamas, plot to dispatch the other’s children, the scene depicts Ino crowing over the vanquished Themisto. The work was one of Euripides’ best-loved plays but has largely been lost.

In a further boon for classicists, the authors noted that in addition to the Euripides texts, “several other fragments of papyrus [were found] whose publication is forthcoming.”