Art World

‘Everybody Owes Him a Debt of Gratitude’: How Mitchell Algus Became New York’s Most Beloved, Least Successful Art Dealer

Mitchell Algus gave some of the greatest artists working today their first shows. So why does nobody know his name?

Mitchell Algus gave some of the greatest artists working today their first shows. So why does nobody know his name?

Rachel Corbett

The celebrated art dealer Mitchell Algus marked the 25th anniversary of his gallery last year. But no one seemed to notice.

That’s probably because he didn’t actually get around to commemorating the anniversary until now, a year later, with a series of group exhibitions that highlight some of the artists he’s shown over the years, often long before they achieved fame elsewhere. The list includes many names who are now regarded as boundary-pushing pioneers of contemporary art: Barkley Hendricks, Betty Tompkins, Martha Wilson, Judith Bernstein, Joan Semmel, and Lee Lozano, among others.

The consummate underdog, Algus is used to being overlooked and off schedule. He has never hired staff and rarely sells the work he shows. “I don’t think the collectors ever understood what I did, until the artist goes to Hauser & Wirth or Mary Boone,” he says—as was the case of Lozano and Bernstein, respectively.

In an art market that increasingly benefits mega-dealers but has never been less hospitable to smaller outfits, Algus represents a vanishing breed: a gallerist who is dedicated to finding work that others have dismissed or ignored, without interest in a major payoff. “His heart, and his history, are, always were, truly in it,” the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter tells artnet News. “He’s a driven and tender archaeologist.”

Algus has managed to stay afloat for 25 years, through multiple booms and busts. But the current climate has left him feeling more discouraged than ever.

For 23 years, Algus supported himself and the gallery by teaching science at a Queens public high school, opening the space up on nights and weekends. But the day job, from which he retired in 2014, afforded him the independence to pursue the cerebral, often unprofitable shows he enjoys most.

“Mitchell is an iconoclast, and there is usually no reward for that,” says curator Bob Nickas. “Neither is there any appreciation from the blue-chip galleries that have profited from all the legwork and brain-work he has done over the years.”

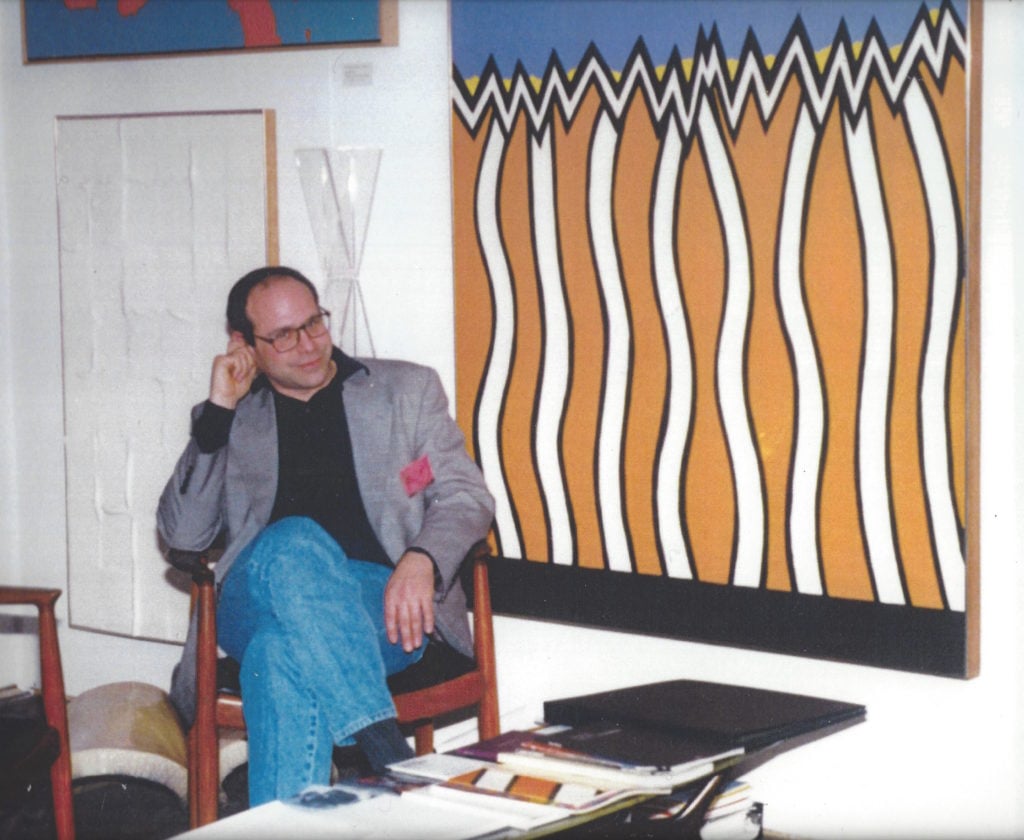

Installation view of Judith Bernstein’s show at Mitchell Algus Gallery in 2007.

Many of the artists Algus championed are currently enjoying unprecedented market and critical acclaim. Bernstein was recently the subject of a solo exhibition at New York’s Drawing Center; Hendricks figures prominently in Tate Modern’s traveling exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” and the Prospect.4 Biennial in New Orleans. A number of others were included in a special section dedicated to explicit art made by women at Frieze London. Algus, for his part, says he couldn’t afford to participate.

“Everybody owes him a debt of gratitude,” Cotter says. “Most important were the entire careers—particularly careers of women artists—he helped restore and reposition just by paying attention.”

Although Algus has made some peace with the financial realities of his business, he is suddenly confronting a new kind of deficit he never imagined: gallery-goers. Lately, he considers it a good day if three people come by his Lower East Side space. “The audience is the real worry now. Why do shows if nobody else is coming?”

Algus blames the rise of art fairs for dominating not just the market, but also the audience. Fairs are “a death sentence,” he says. “For galleries that aren’t Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth, nobody expects to make money; you expect to pay the fine of the booth for the crime of going to the art fair. It’s the only place you see these collectors.”

For Algus, the present moment is probably the closest he’s come to considering closing his doors for good. Losing the legendary space would be a blow not only to its fans, but also to the broader art ecosystem, which would would lose an eye at the margins that has consistently brought to light artists that would otherwise be ignored or rejected.

“It’s a rarefied group of people who go see Mitchell Algus shows,” says Jay Sanders, executive director of the nonprofit gallery Artists Space. But from those small shows, major careers have sprung. “Look at Tompkins, Lozano—he was the person to find the work in their attic. He’s a secret source,” Sanders says.

Installation view of Agustin Fernandez works at Mitchell Algus Gallery in 2006.

Algus was born in 1954 and grew up in Brooklyn and Long Island. His father was a dentist who loved art and often took his son to galleries in Manhattan. Algus went on to receive a PhD in physical geography from McGill University in Montreal, doing his field research in the Canadian Arctic.

He maintained his interest in art throughout, but when he took an art class in college and got a B, he gave up the idea of pursuing it academically. “Why am I going to do something and get a B? Forget it,” he says. So he focused instead on science, but still spent hours in the art library poring over old issues of Art International and Artforum.

In the mid-1980s, he moved to New York City and started to make his own artwork. He dismisses his practice now as “just fooling around,” but he showed several times with Pat Hearn, a leading dealer in the East Village at the time. “He was making these fascinating sculptures that looked like amoebas but were made out of upholstery material with fringe and buttons,” says the artist Jack Pierson, who befriended Algus and later went on to curate a show at his gallery in 2003. “It was incredible work.”

In 1989, Algus partnered with his friend Licha Jimenez to run her gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. He quit making his own work and focused on the space full time, recruiting historical figures such as Robert Mallary and Harold Stevenson to show there. In 1992, he opened his own gallery on Thompson Street in SoHo, alongside such up-and-coming dealers as Gavin Brown and Friedrich Petzel. “David Zwirner opened up a couple blocks away,” Algus said, trailing off. “…Two separate trajectories.”

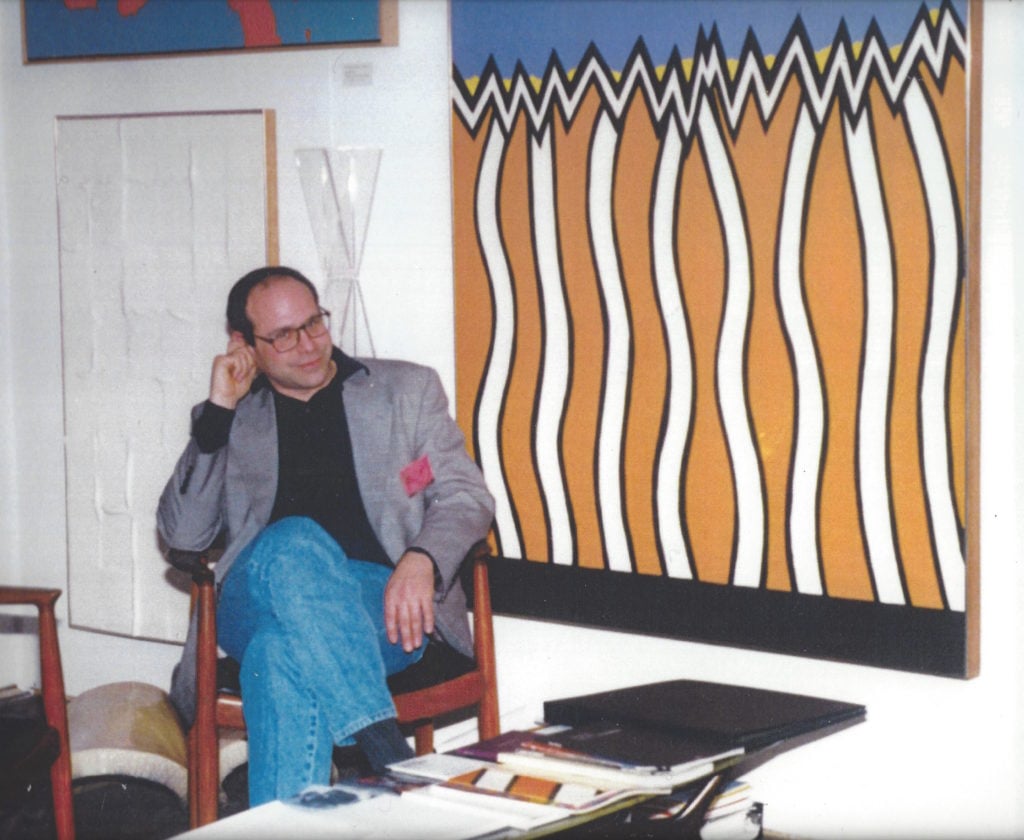

Harold Stevenson with his painting Gun in 2002.

Algus debuted his new gallery with a single painting, Harold Stevenson’s 40-foot-long male nude, New Adam (1962), which wrapped around the gallery in several panels. “Sensational, and until then, as far as I know, completely forgotten,” Holland Cotter says of the work, which is now in the collection of the Guggenheim. “It was clear right away that Mitchell was looking at times and places and kinds of art no one had looked at for ages.”

A few years later, in 1998, Algus presented a solo show of work by the then-unknown painter Lee Lozano, who was suffering from cancer and would die the next year. He tried to sell her drawings for $1,500, but “I couldn’t do it,” he says. After Nickas, then a curator at MoMA PS1, saw the show, he decided to do a survey of Lozano’s work at the museum. Soon thereafter, Hauser & Wirth started representing Lozano’s estate and those drawings suddenly cost $65,000—”the same drawings,” Algus says.

Algus’s career is full of moments like this: discoveries he made before the rest of the world was quite ready for them. The painter Betty Tompkins hadn’t had a solo show in 15 years when the art critic Jerry Saltz passed Algus along some slides of her monumental “Fuck Paintings,” depicting genitalia in photorealistic detail. Algus offered her a show in 2002.

“He picked me up and gave me a chance when nobody would breathe in my direction,” Tompkins says. “He really did pick me up off the street.” Those early paintings can now fetch upwards of $650,000. At the time, however, Algus had a tough time selling them to anyone except a few adventuresome collectors, including the artist Robert Gober.

Betty Tompkins (R) and her former painting student Joan Rivers at Tompkins’s 2002 show at Mitchell Algus Gallery. Photo by Walter Robinson.

“When I saw the Betty Tompkins paintings I had no doubt that they were consequential and that I’d like to own one,” says Gober, who bought one of the works from that first show and has since donated it to the Brooklyn Museum. “Mitchell has a great eye.”

The gallery’s direction took a sharp turn in 2010 when Algus entered into a tumultuous business partnership with dealer Amy Greenspon, the daughter of art collector William Stuart Greenspon. With her connections and his erudite taste, it seemed like their collaboration could be a serendipitous case of opposites attracting. But it was not. “As with most partnerships, the people who have the money have the gallery,” Algus says. “I got to do some good shows but it wasn’t my gallery.” The pair went their separate ways in 2015.

Installation view of works by Harold Stevenson and Leonid Berman in Algus’s “25 Years: Representation” show.

That year, Algus reopened on his own in the Lower East Side. He is still there, staffing the desk himself, five days a week. It may take a bit of legwork to seek him out, but those who do find it worth the trouble. “He always chats, he has a lot of patience for artists, and loves to share the information he’s acquired,” Pierson says.

But while a lot of people root for the underdog, few, it turns out, show up to its second-floor gallery on an out-of-the-way stretch of Delancey Street. Sanders notes: “His new space is great but, like him, it’s hidden in plain sight.”

Mitchell Algus Gallery’s anniversary show “Representation” is on view through April 1.