Artists

Ewa Juszkiewicz On What Hides Beneath the Veils of Her Faceless Portraits

The artist deconstructs social ideals of feminine beauty throughout art history.

The artist deconstructs social ideals of feminine beauty throughout art history.

Margaret Carrigan

At the April opening of her solo show in Venice, “Locks with Leaves and Swelling Buds,” artist Ewa Juszkiewicz was wearing a crisp ankle-length cherry-red dress by Valentino with two large architectural rosettes at the hips, an outfit that was at once romantic and precise, demure but also borderline confrontational. Rarely would it feel germane to comment on an artist’s fashion choices, except that, in this case, the same descriptors could be applied to Juszkiewicz’s paintings.

Fashion is central to the Polish painter’s portraits, especially so since the identity of the sitters is concealed by fabric, flora, or elaborate hair styles. Using traditional European oil painting techniques, leveraging thin layers of paint, and often referencing specific artists, she creates beautifully rendered images of what appear to be women, but what are often only signifiers of a woman in an attempt to deconstruct the social ideals of feminine beauty and gender itself. While she says the history of portraiture has always interested her, the big draw has always been the details.

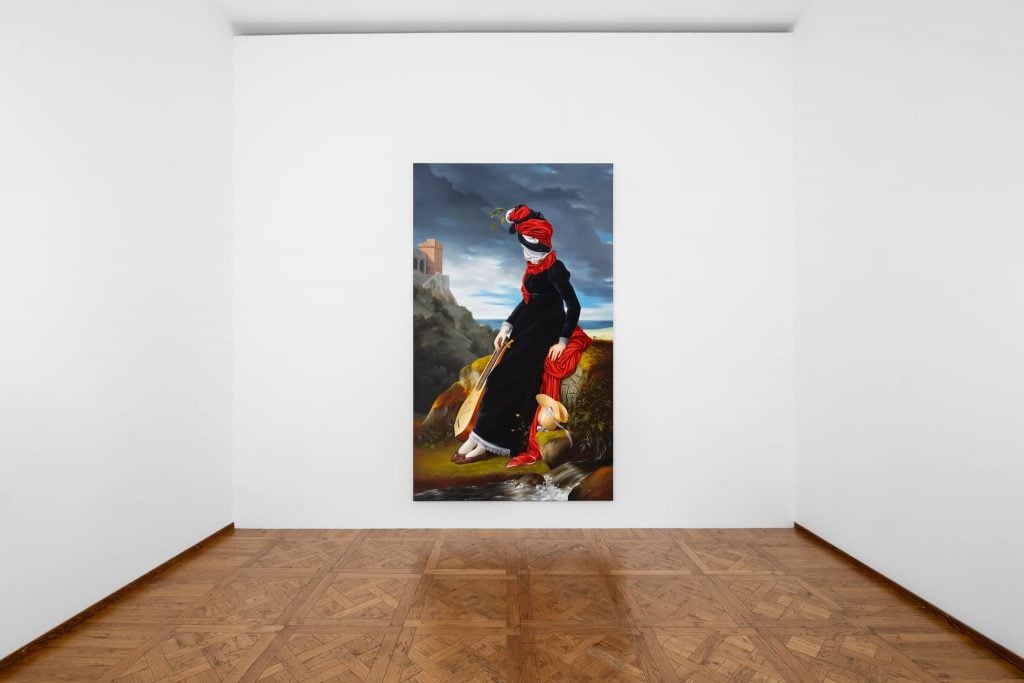

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Untitled (after Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun) (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

“You can see fashion evolve in art. Even when I was a teenager, I loved to go to museums and look at portraits and how styles have changed: the clothes, the hair, the accessories,” Juszkiewicz said in March in a phone call from her studio, where she was busy prepping several of her canvases to travel to Venice for the show. An official collateral event of the 60th Venice Biennale and organized by the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, “Locks with Leaves and Swelling Buds” features 15 paintings, five of which were specially created for it, and briefly surveys the evolution of some of the artist’s iconic motifs.

The details in portraiture, she explained, can be very psychologically rich. “These are symbols of beauty and status but also sources of anxiety… fashion can be liberating but also oppressive.”

Over the last decade, Juszkiewicz has become known for her surrealist interpretations of traditional portraits of women, inspired by the work of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, a French portrait artist who was the official court painter for Marie Antoinette. Her first portrait in a series that now includes over 70 paintings, Straw Hat (after Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun) (2012), shows the titular artist with two sections of hair divided down the middle of her face.

Installation views of Ewa Juszkiewicz, Palazzo Cavanis, 2024 / © Ewa Juszkiewicz. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Eleonora Paciullo.

As a woman, Vigée Le Brun was an outlier in the male-dominated field of painting—especially court painting—in the 1700 and 1800s, which was part of Juszkiewicz’s attraction to her. Vigée Le Brun’s attention to details in her paintings of aristocratic women hinted at aspects of their personalities, whereas many other portraitists idealized female subjects beyond recognition.

“It was hard not to see the patterns repeated in portraiture. In some ways, they were more like still lifes,” Juszkiewicz explained. When she started painting her own portraits of women, the artist “wanted to create a dialogue with the past, to question these conventions.”

Many of Juszkiewicz’s best-known and most coveted works reference specific women, including Straw Hat, as well as Portrait of a Lady (After Louis Leopold Boilly) (2019), which features all the hallmarks of Boilly’s original 1807 painting of Madame Saint-Ange Chevrier, except that, in Juszkiewicz’s version, her face is wrapped in the same white and red fabric of her dress with a few wisps of hair and some plant fronds sticking out of the top.

The elements of absurdity that she introduces within these paintings subvert not only the genre of portraiture but the linear narrative of patriarchal history that has long sidelined and wholesale erased women.

“It’s not my goal to make a super historical reproduction,” Juszkiewicz said; instead her aim is to question how identity is constructed over time. While many of her portraits may have been inspired by certain women, they are ultimately a portrait of every woman.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Lady with a Pearl (after François Gérard) (2024). Courtesy Ewa Juszkiewicz and Almine Rech.

Growing up in the medieval city of Gdańsk, which was heavily bombed and shelled in World War II, the artist said the past “always felt very present.” Citing historical influences ranging from Dutch still life painters like Clara Peeters and Rachel Ruysch to Surrealists like Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington, and Leonor Fini, as well as contemporary artists concerned with identity such as Cindy Sherman and Wangechi Mutu, Juszkiewicz adds that the creative liberties she takes with traditional subject matter further recontextualize the role of women in the canon of art history.

Amid a general upswell of institutional and market attention paid to women artists, Juszkiewicz, who has been represented by Almine Rech since 2019, has seen her market mushroom in the last five years, leading to some concerns of speculative pricing at auction. Gagosian started representing the Warsaw-based artist in the U.S. and Hong Kong in 2020 and, in 2021, her works began going under the hammer. Since then, nearly 80 works have appeared at auction. The height of Juszkiewicz’s secondary market to date came in 2022, when three works sold for over $1 million, among them Straw Hat. That also includes Portrait of a Lady (After Louis Leopold Boilly), which set the auction record for the artist when it sold for $1.5 million—420 percent more than its $200,000 to $300,000 presale estimate—at Christie’s New York.

Installation view of Ewa Juszkiewicz’s In a Shady Valley, Near a Running Water (after François Gérard) (2023) at Palazzo Cavanis, 2024. © Ewa Juszkiewicz. Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Eleonora Paciullo

A similarly styled portrait is at the heart of “Locks with Leaves and Swelling Buds,” which is on view at the Palazzo Cavanis through September 1. In a Shady Valley, Near a Running Water (after François Gérard) (2023) debuted in Juszkiewicz’s solo show at Gagosian’s Beverly Hills outpost last November. It is a nine-foot-high interpretation of Gérard’s 1804 portrait of Countess Katarzyna Joanna Gabrielle Starzenska, a prominent figure in the Polish aristocracy whose face is obscured by the same cloth that comprises her dress, topped off with a few leaves.

“She was famous in her time; she was an idol,” Juszkiewicz said of Starzenska at the opening of the show in April. “But when I looked at her eyes [in the Gérard portrait], there was so much melancholy, and I saw resignation in her pose. She was wearing a heavy, dark dress despite being on a springtime walk. I wanted to capture that feeling.”

Many of the artist’s floral-focused works are also included in the Venice exhibition, including Bird of Paradise (2023), on loan from the Albertina Museum in Vienna. “These works I consider in the genre of historical vanitas paintings,” Juszkiewicz said, adding that there is an element of life and death—the plants are all in different stages, from bud to bloom and leaf. “There is also a theme of being overgrown, the fusion of hair and plant, and blurring the boundaries of what is human.”

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Bird of paradise” (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Serge Hasenböhler Fotografie

Additionally, there are two new iterations of her hair works, which feature less historical influences and more, well, hair. “Hair is very interesting; it’s often a status symbol,” the artist said. Juszkiewicz’s Ginger Locks, bought by the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami in 2021 from Almine Rech, became a fashion object and status symbol in and of itself last year, when Louis Vuitton started selling a $10,500 bag bearing a print of it.

Juszkiewicz sees the collaboration as a sculptural outgrowth of her painting. “Transferring my work into a 3D object, it can now be brought into a public space. The image takes on new meanings in different environments now,” she said, adding that the “fusion of art and fashion is not so unusual, it has been connected for centuries. The line between the two is often very blurred.”

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Red Dress (2024). Courtesy Ewa Juszkiewicz and

Almine Rech.

The increased attention, both within the art market and on the fashion retail side, has a double standard to it. While male artists whose commercial star rises quickly are often billed as “critically acclaimed” for their individual creativity or, if their work is referential, their art historical acumen, women artists in the same position are frequently lumped together as part of a wider stylistic trend that offers a “market correction” or “rights the historical balance.” It’s a heavy mantle to carry as an individual artist, much like a dark velvet dress on a refreshing spring walk.

When asked how she manages the surge of attention being paid to her and her work, Juszkiewicz, who is 40 this year, said she approaches the hype with caution.

“I don’t focus too much on the increased interest,” she said, noting that frequently used terms like “market darling” and “rising star” collapse an artist’s oeuvre to only their latest works that have caught the market’s interest. It’s perhaps similar to the the way idealized portraiture collapses a living, breathing woman into an aggregation of socially constructed signifiers that obscure who she actually is. “I will continue to make what I like. It’s not like I just appeared out of nowhere. I’ve been painting for years and working on this series [about women] since 2011.”

Trends, after all, whether in fashion or in art, can be liberating but also oppressive.