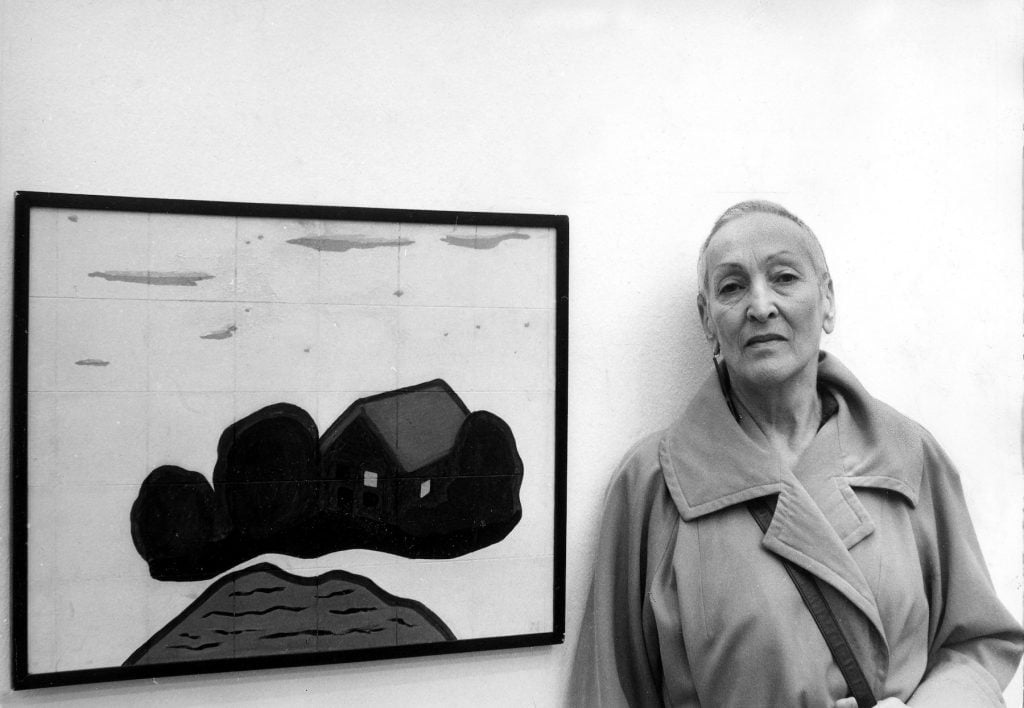

If you know the name Meret Oppenheim, you probably associate the artist with one thing: fur. A new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, however, proves the Surrealist to be an artist of endless creativity and incredible versatility who drew, painted, and sculpted in a wide range of media and materials.

“She just had a remarkable imagination and unrivaled ability to get up in the morning and never do the same thing twice,” Anne Umland, the museum’s senior curator of painting and sculpture, told Artnet News. “It’s pretty radical that throughout her five-decade career, she managed to remain committed to a very otherworldly, witty, whimsical sensibility.”

The show, titled “Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition,” is the artist’s first U.S. exhibition in 25 years, and it features numerous pieces that are being shown in the country for the first time. It originated at Switzerland’s Kunstmuseum Bern, which has the world’s largest holdings of the artist’s work, and is co-organized by the two museums and Houston’s Menil Collection.

“We’re not going to see such a range things brought together again anytime soon,” Umland said, noting that the museum had long been interested in a dedicated Oppenheim show and jumped at the chance when Bern suggested the collaboration. “If there was ever a time to do an Oppenheim show, this was it. This was an extraordinary, once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Meret Oppenheim, Object (Objet) (1936). Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

MoMA is the last stop on the transatlantic tour, and it boasts one major highlight missing from the other venues: Object, the fur-covered teacup, saucer, and spoon that earned Oppenheim her place in the art history books.

Too fragile to travel, the work is one of the mainstays of the MoMA collection—even though the acquisitions committee actually rejected it on multiple occasions.

“When it first arrived in 1936, it sort of became the poster child for everything that was absurd and anti-art about the Surrealist approach to art making,” Umland said.

Meret Oppenheim, Pair of Gloves (1985). Collection of the Kunstmuseum Bern, gift of Ruth von Büren. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Fortunately, founding director Alfred Barr had the good sense to buy Object himself after it made its debut at MoMA’s “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism” exhibition that year, giving the institution time to come around to the groundbreaking work.

Oppenheim, who was born in Germany in 1913, was just 22 when she made the work, a time when she was supporting herself by making jewelry. A fur-covered bracelet she’d fashioned caught the eye of Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar while the three were out to lunch. When Picasso commented that anything could be improved by a fur coating, Oppenheim’s wheels went spinning.

Meret Oppenheim, Daydream (Wachtraum), 1929. Collection of the Kunstmuseum Bern. ©2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Pro Litteris, Zurich.

Having made her name in art at such a young age, Oppenheim had a somewhat complicated relationship with Object. She was proud of her role in Surrealist movement as a young woman and her ability to channel the avant-garde ethos even as she resisted being defined by a single piece. But it also overshadowed other aspects of her career.

“It’s the sort of thing that’s just absolutely unforgettable,” Umland said. “The artist Jenny Holzer one described it as ‘absurdly sublime.’ It’s also both seductive and repulsive—an everyday object and yet made strange. It takes something that is associated with decorum and domesticity, and makes it rather bestial and spectacularly other.”

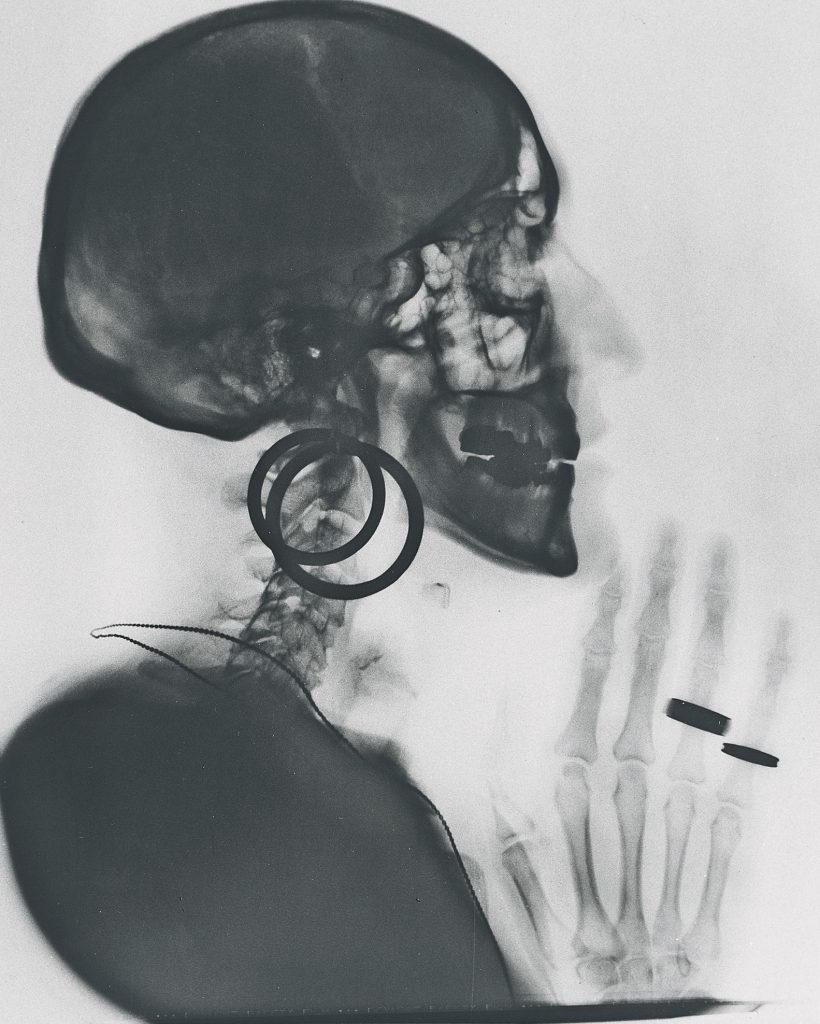

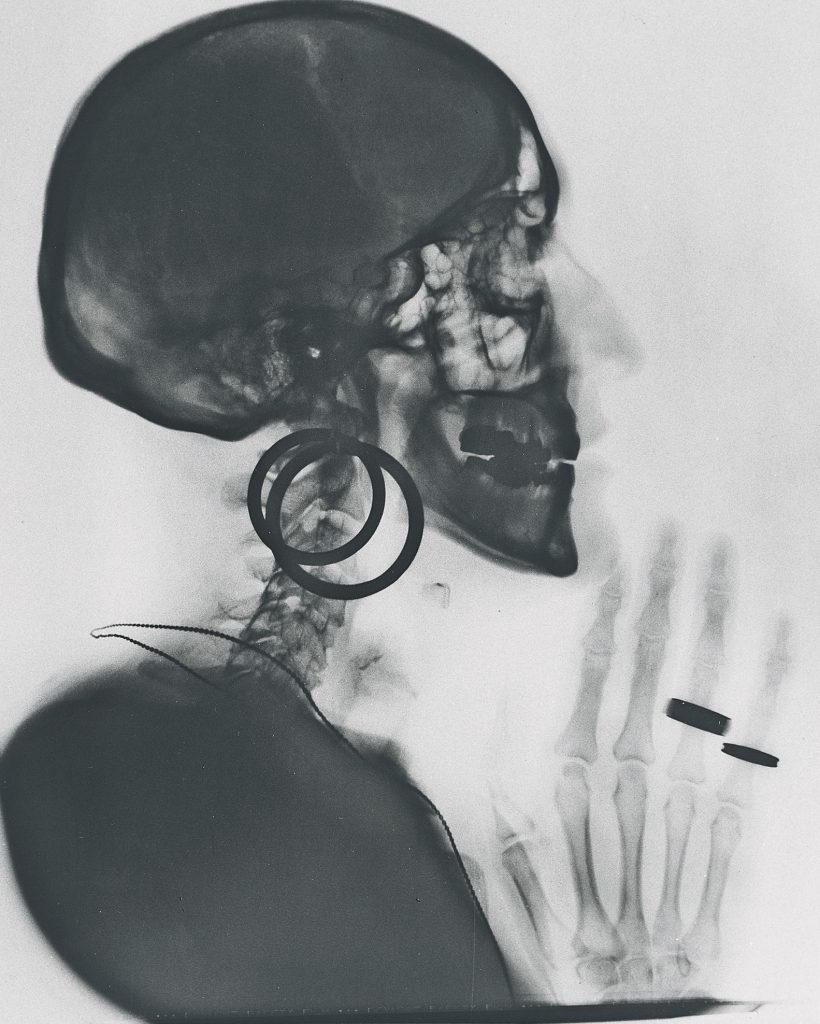

Meret Oppenheim, X-Ray of M.O.’s Skull (Röntgenaufnahme des Schädels M.O.), 1964/1981. Hermann and Margrit Rupf Foundation. Kunstmuseum Bern. Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The work also marks Oppenheim’s first exploration into themes that would become recurring.

“Oppenheim’s five-decade career writ large works to undermine longstanding dualisms or opposition between things like human and nature, animate and inanimate objects, male and female—all of those binaries are things that the fur tea cup undoes, and that the larger body of work continues to undermine in innumerably different and varied ways,” Umland added.

Installation view of “Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition” on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Her sculpture The Green Spectator (1959) blocks a doorway between galleries, a design choice envisioned by the artist in set of 1983 drawings for a possible retrospective of her work. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

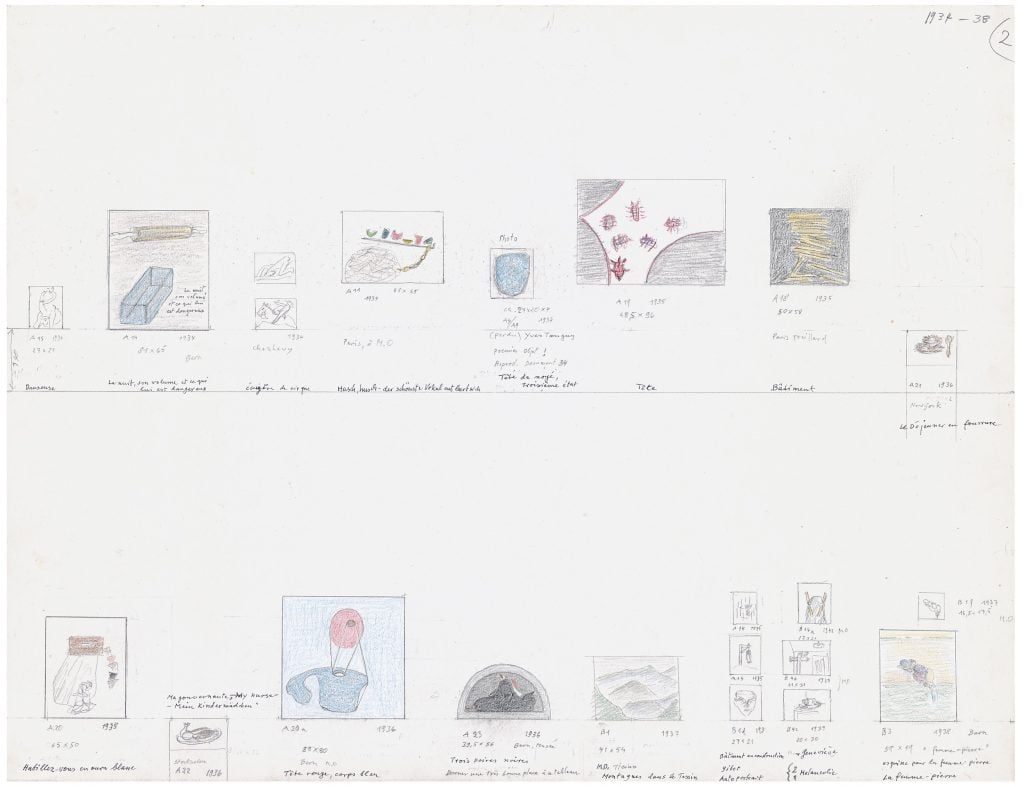

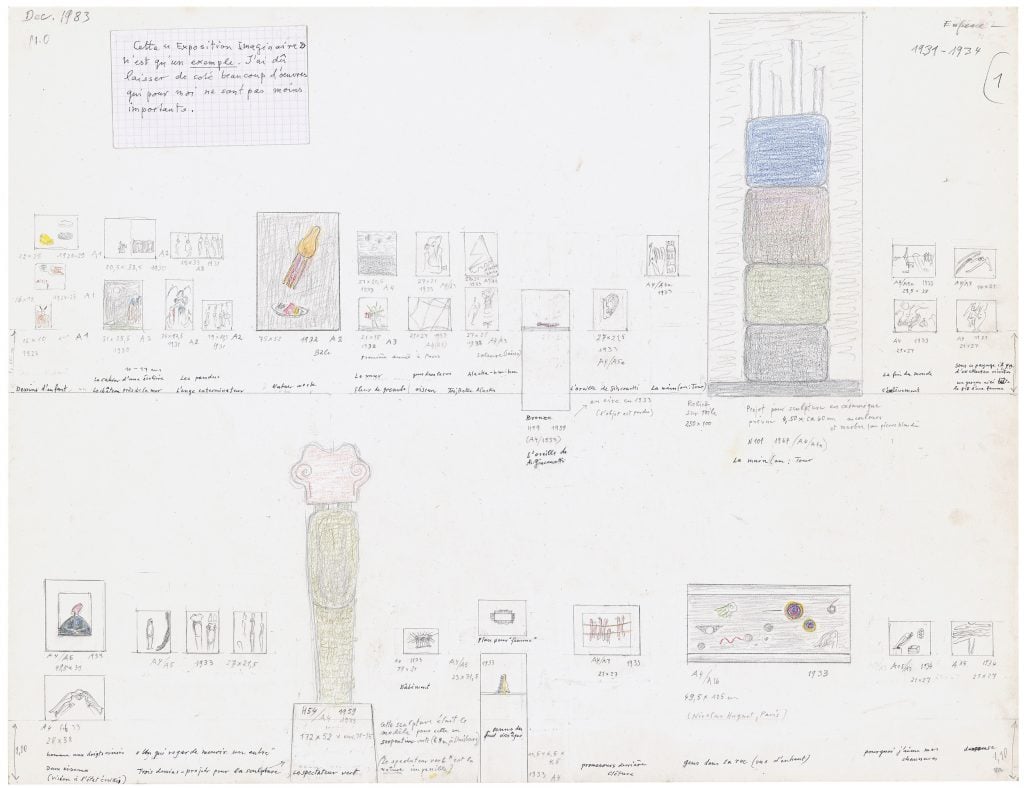

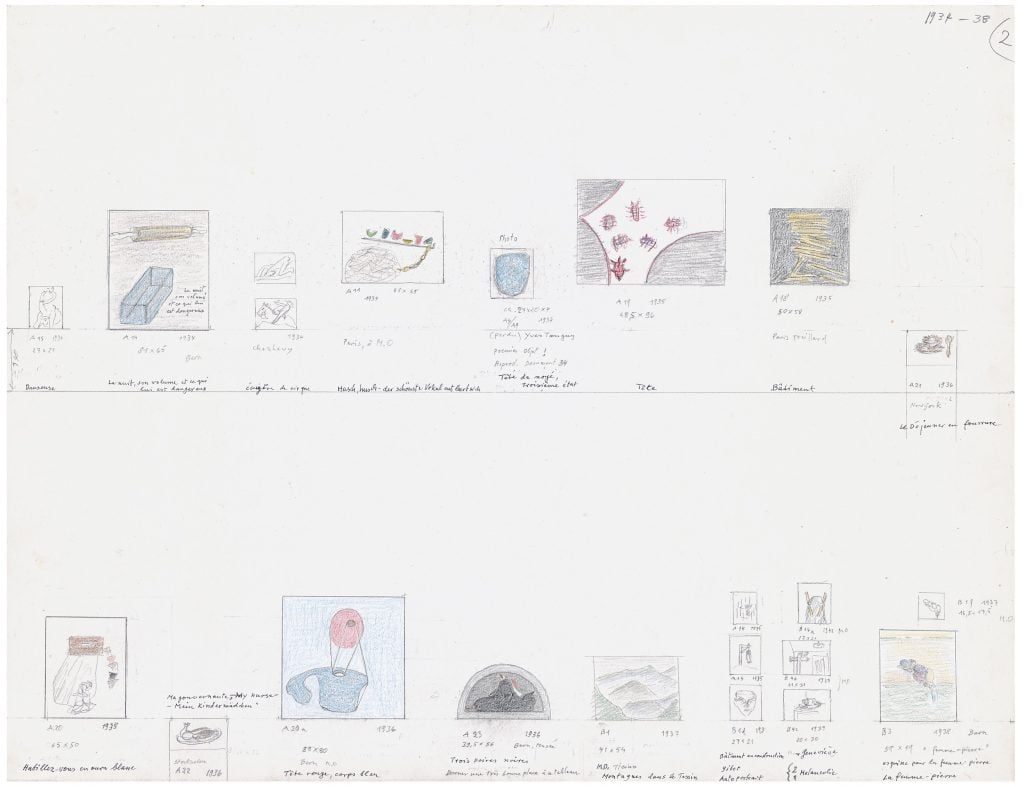

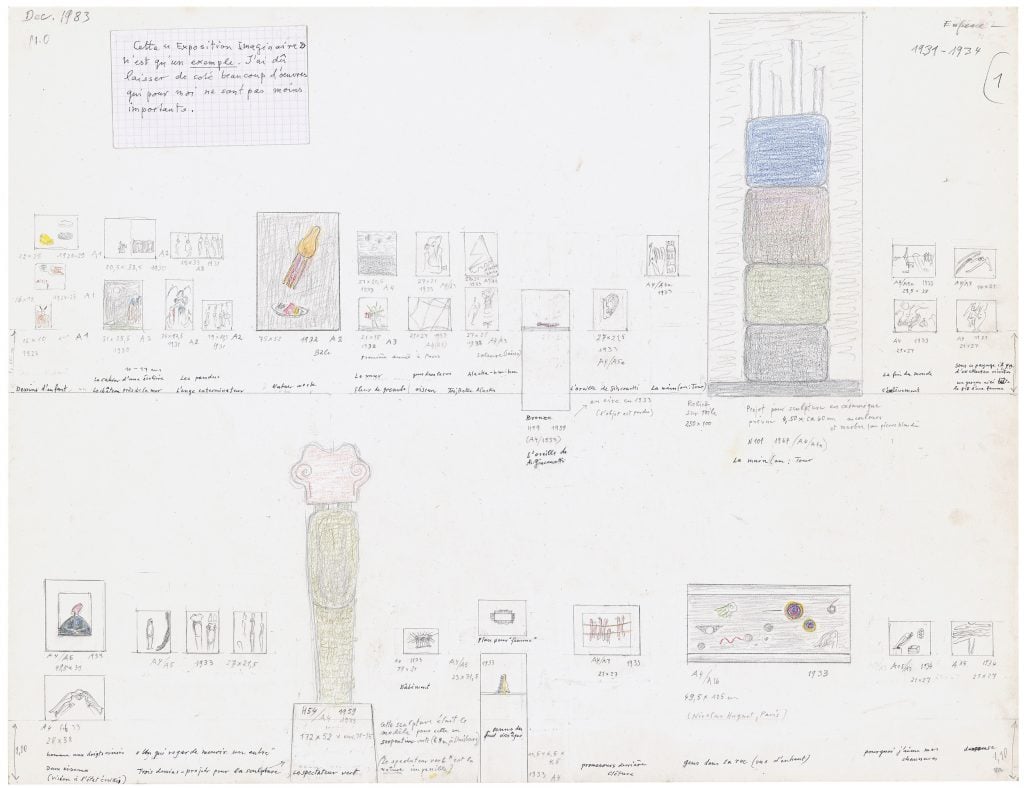

The show’s title, “My Exhibition,” comes from the fact that it was curated partly in response to Oppenheim’s own carefully illustrated plans for a retrospective of her work, a series of drawings from 1983 that lay out her career in chronological order.

Though the curators at MoMA gave themselves freedom to deviate from Oppenheim’s plans, the placement of her tall 1959 sculpture The Green Spectator does block a doorway between galleries, as the artist designed.

Meret Oppenheim, M.O. My Exhibition (M.O.: Mon Exposition), 1983. Bürgi Collection, Bern. ©2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ Pro Litteris, Zurich.

Meret Oppenheim, M.O. My Exhibition (M.O.: Mon Exposition), 1983. Bürgi Collection, Bern. ©2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ Pro Litteris, Zurich.

In addition to Object, the show features a handful of other works from MoMA’s collection. There’s a striking X-ray photograph of the artist’s head, recently acquired at an auction in Europe, and a large painting Red Head, Blue Body, that Oppenheim used to hang over her bed, left to the museum in her will.

“She saw it as very important to her early Surrealist years, and she wanted to make sure the fur tea cup had a companion. It’s from exactly the same year, which does a lot to undo this notion that she only made fur-covered objects,” Umland said.

Meret Oppenheim, Red Head, Blue Body (1936). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Meret Oppenheim Bequest. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

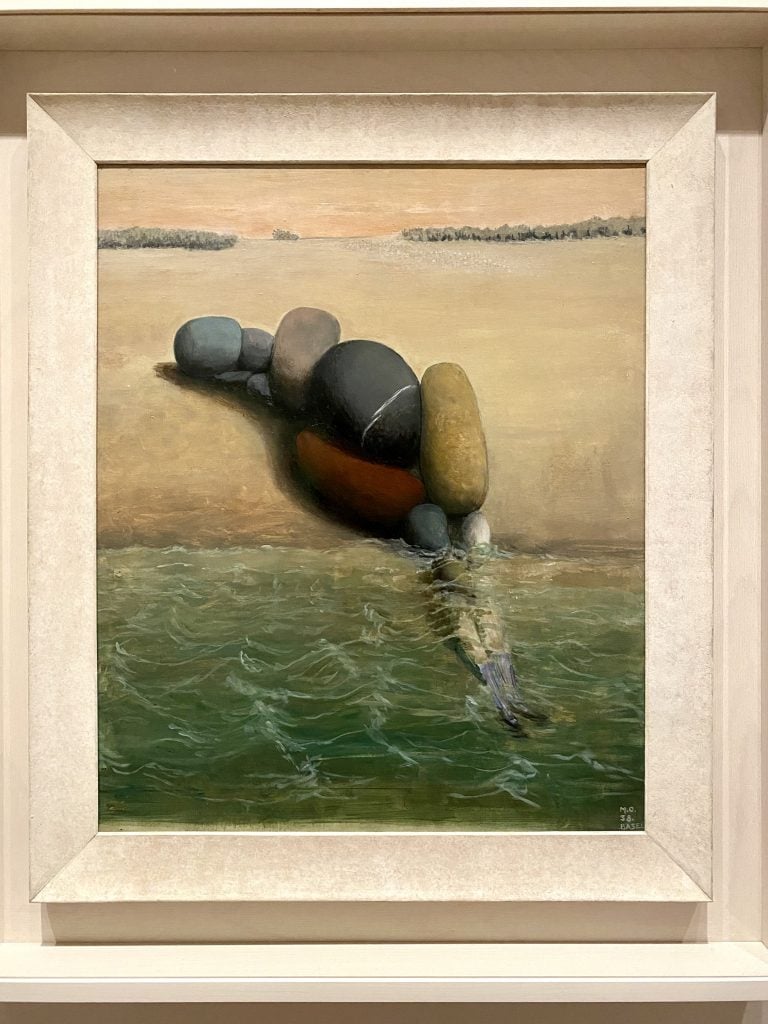

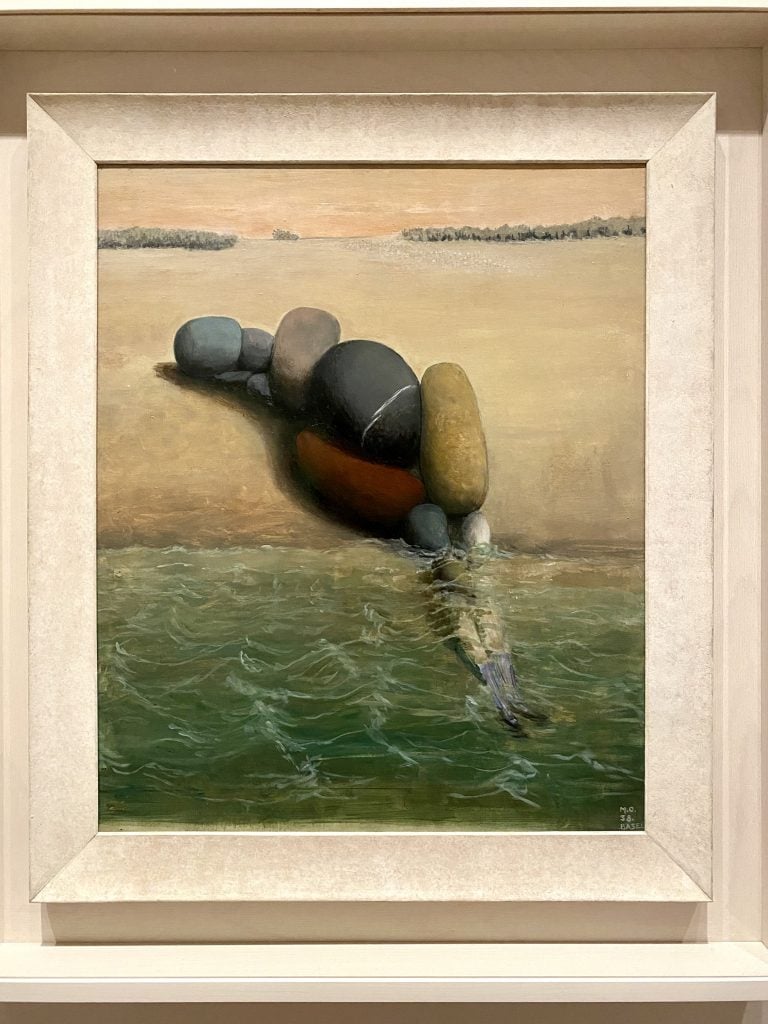

But most of the works on view are loans from Switzerland, where the bulk of Oppenheim’s oeuvre still resides. That means there’s a lot to discover in the exhibition, from delightful collages to surprisingly deft oil paintings that reveal Oppenheim’s considerable draftsmanship skills, such as Stone Woman (1938).

“There’s this bravura technique that renders all different sorts of textures, you can look at the shimmering surface of the water and underneath it see that the little legs of the stock figure have socks and Mary Jane shoes on,” Umland said of the work. “This has almost Old Master levels of glazing and applying paint in translucent layers.”

Meret Oppenheim, Stone Woman (1938). Photo by Sarah Cascone.

“That idea of magic and enchantment and transformation, themes of isolation and entrapment and loneliness that are so much of Oppenhein’s world in the late ’30s are right there in that painting,” she added.

Viewers might also not expect Oppenheim’s knack for assemblage, mashing up found objects to delightful Surrealist effect. Another highlight is Animal-Headed Demon (1961), a Neoclassical clock case the artist altered by plunging a large wedge of wood through its face, and adorning it with ceramic buttons.

And then there’s Oppenheim’s undeniable sense of humor. One 1936 work, Ma Gouvernante (My Nurse), presents a pair of white high heels upside down on a silver platter, trussed with twine like a roast chicken, decorative paper frills covering the heels.

Meret Oppenheim, Ma Gouvernante (My Nurse), 1936. Collection of the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Shoes again come into play decades later with the 1967 sculpture The Couple (with Egg), of a pair of boots sewn together at the toes, sitting next to an egg perched upon nest of coiled shoelaces.

“She was trying to imagine what shoes left outside a hotel room door would do—of course they would mate!” Ulmand said.

Meret Oppenheim, The Couple (with Egg), 1967. Courtesy of the Sprengel Museum Hannover. On loan from the Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd Foundation. ©2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Pro Litteris, Zurich.

Even for the curator, the sheer breadth of the artist’s wildly inventive career was unexpected. “Being someone who has worked as a scholar and art historian and curator of the interwar period, I had not realized just how expansive the body of work is,” Ulmand said. “To see what she went on to do in the 1940s and ’50s and ’60s and ’70s is just mind boggling.”

“Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, October 30, 2022–March 4, 2023.