People

Experts Weigh In on Jeff Koons Copyright Infringement Lawsuit

What will the determining factors in the case be?

What will the determining factors in the case be?

Brian Boucher

Jeff Koons may be the most sued artist in history, having been targeted with copyright infringement complaints no fewer than five times, and this week brings news of yet another suit against the master appropriator.

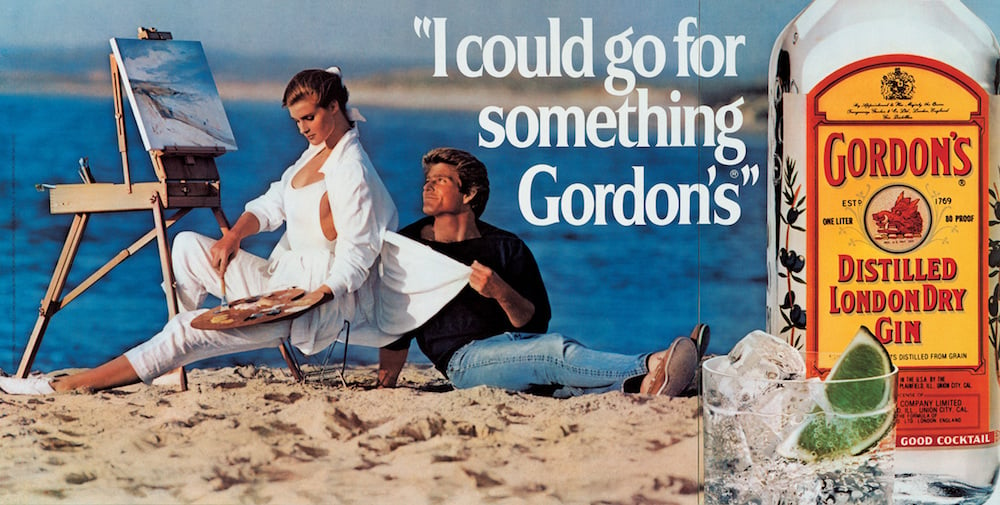

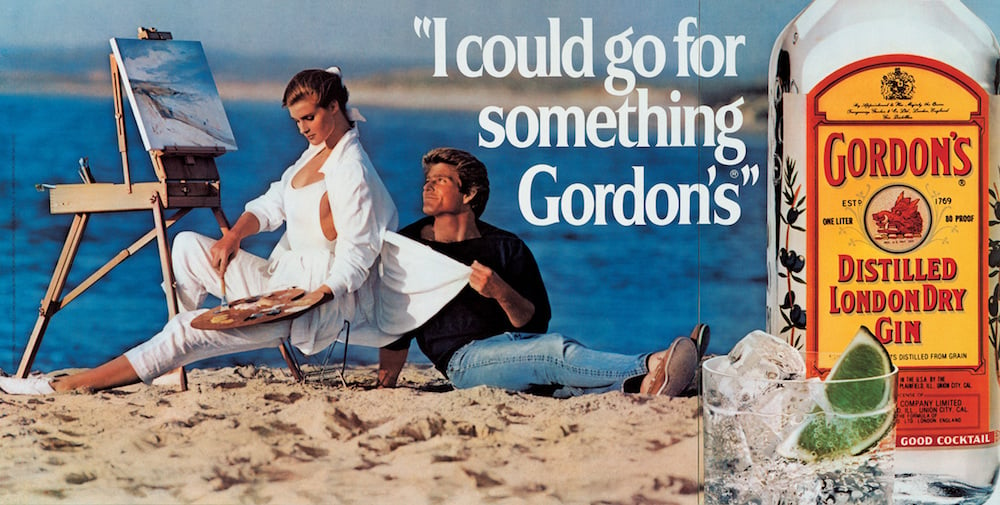

New York photographer Mitchel Gray has brought suit against Koons in the district court in New York for using an image he shot for Gordon’s Dry Gin in the 1986 artwork I Could Go For Something Gordon’s, from his series “Luxury & Degradation.” The suit also names Phillips, which sold an edition of the work for $2 million in 2008 and has kept an image of the work on its website ever since.

While the suit hinges on a work that’s 30 years old, Gray claims it’s within the statute of limitations because he only discovered the infringement this past summer and in copyright infringement cases, the clock starts ticking when the infringement is discovered, not when it’s committed.

That leads us to one of the curious facts about this case. How in the world did Gray not know about this work by one of the most famous artists in the world, especially after his blockbuster, museum-wide 2014 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art? The complaint indicates that he only learned of the work only in July 2015.

The legal complaint seeks to have it both ways on that issue. It points out that Phillips has displayed the work extensively in furtherance of its attempt to profit from the sale of the work and to promote to its brand. However, the complaint undercuts that argument when it states that the work has been “only occasionally displayed publicly, appearing in museums and galleries a limited number of times.”

So which is it? Has it been publicly displayed or not? In an email, Fletcher declined to clarify exactly how Gray had discovered the offending image. Fletcher declined to comment about any aspect of the case, and Koons’ studio did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

According to the complaint, Gray is a commercial photographer who has made a living on “fashion, lifestyle, portrait, sports, and fine art images.” Gray’s photo shows a couple on a beach, the woman working on a painting as the man tugs at her smock. The image is captioned, “I could go for something cool, crisp, and Gordon’s,” along with an image of a bottle of Gordon’s gin. Gray granted Gordon’s a temporary license to use the image, but retained copyright. Koons’s work makes a “near-identical copy” of the advertisement, according to the complaint. Taking a look at it, we do see that Koons’s work makes some design changes: it repositions the gin bottle, changes the typeface, transposes the text onto the image, and trims the phrase in the ad to “I could go for something Gordon’s.”

Koons and the other appropriator extraordinaire, artist Richard Prince, have been at the center of landmark cases in intellectual property law. Prince was sued by French photographer Patrick Cariou in a case that dragged on for several years and generated numerous dissertations’ worth of commentary.

In the end, the court decided that the artist was within the “fair use” provisions of copyright law, which allow for artists to use copyrighted material if their use of it is sufficiently transformative or creates new ideas.

“We’re post Cariou v. Prince now, so the courts are more tolerant than ever of fair use,” says New York artist and writer Nate Harrison, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on appropriation art and intellectual property.

“It’s a work in which Koons fully appropriated his source, Sherrie Levine–style,” Harrison added. “So in this instance, the case for Koons having transformed the original would have to rely almost entirely on the status of Koons’ work as art. From an aesthetic point of view, it’s difficult not to see this as pure pilfering, in line with much postmodernist appropriation at the time.”

Attorney Claudia Ray, of New York firm Kirkland & Ellis, will also be watching the case closely. At a 2011 panel on appropriation art, she staked out a skeptical position, saying, “One question that seems never to be asked is, ‘Is there any compelling reason an artist could not ask permission to use an image and pay for the use of it?'”

“Given that, as shown in the Complaint, Mr. Koons’ work seems to have incorporated Mr. Gray’s work with little or no alteration, it will be very interesting to see how the court deals with the question of how much, or little, a second artist must do to a work in order for his or her use of another artist’s work to be considered a fair use,” she told artnet News in an email. “This question remains an open one in the wake of the Second Circuit’s 2013 decision in Cariou v. Prince, where the Court remanded the case to the district court as to five works, concluding that it was ‘unclear whether [the] alterations amount[ed] to a sufficient transformation of the original work of art such that the new work is transformative.’”

NYU law professor Amy Adler points out that Koons is hardened by years of courtroom battle.

“Koons has figured out how to testify in order to win these cases,” she said. “In Blanch v. Koons, which he won after losing three other cases, he used language that looked a lot like the language the Second Circuit used to determine what was transformative, as if it provided him with a road map of how to win a fair use case.”

“One of the problems in the Cariou v. Prince ruling is that it overlooks rephotography and similar work that doesn’t make great physical changes but does make conceptual changes,” she said. “It’s exactly this kind of work that is less protected. What we learned from the Pictures Generation is that works can look alike but have drastically different meanings. We don’t have protections for works like that, though I think we should, and in fact I think the Cariou v. Prince decision only made this situation worse.”

Adler is also skeptical of a claim against Phillips for what she called vicarious liability.

“What the Prince case left open,” she said, “was the issue of Larry Gagosian being liable. The idea was that the gallery should have known that he was a serial infringer. Whether that argument could be extended to Phillips is less plausible. In the Prince case, the theory might hinge on the idea that Gagosian had some control over the arts, which I think is quite dubious, so it’s even more dubious in this case.”