Art & Exhibitions

Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina on Her Plans for a Women’s Museum

She just won WhiteBox's annual award, and plans to keep protesting.

She just won WhiteBox's annual award, and plans to keep protesting.

Cait Munro

It’s been three years since Pussy Riot staged Punk Prayer, their now-iconic performance in which five members of the feminist, dissident Russian art collective entered Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior and denounced president Vladimir Putin via an impromptu rock concert. The act and the subsequent video landed two members of Pussy Riot in prison, and catapulted the group onto the international stage.

Though the group began in 2011 as an anonymous, members-only punk-band-cum-arts-collective, it has recently morphed into a full-fledged activist movement.

“After we uploaded the video, everything started,” Maria Alyokhina, one of Pussy Riot’s most well-known founders, tells artnet News as she lights a cigarette. We’re sitting in the office atop WhiteBox, a non-profit alternative art space in Chinatown where a video of Punk Prayer is being shown as part of “Recycling Religion,” a show examining the role of religion in Russia and Eastern Europe. Pussy Riot is simultaneously being awarded the fourth annual WhiteBox/Richard Massey Foundation “Arts and Humanity Award,” which has previously be given to Ai Weiwei, Karen Finley, and Martha Wilson.

“When we are going to other countries, we always meet people who are Pussy Riot. I think that it’s the best thing. You should not have to have some kind of membership. You should just put the mask on and start protesting,” she says, referring to the brightly-colored balaclavas the band wears during performances.

However, this evolution may be confusing to the general public, and even to those well-versed in the workings of the art world. “New Yorkers don’t get it,” says WhiteBox director Juan Puntes. “New Yorkers expect Pussy Riot to be Pussy Riot and that’s it. That’s what they want to see. Because we shelve things. Critics—and I have some friends who are critics—but critics always want to shelve things. That’s how they train you in academia.”

Puntes curated “Recycling Religion” alongside Russian art dealer, activist, and former political adviser Marat Guelman, who was evicted from his Moscow gallery earlier this year after he hosted an art auction with Alyokhina to raise money for political prisoners.

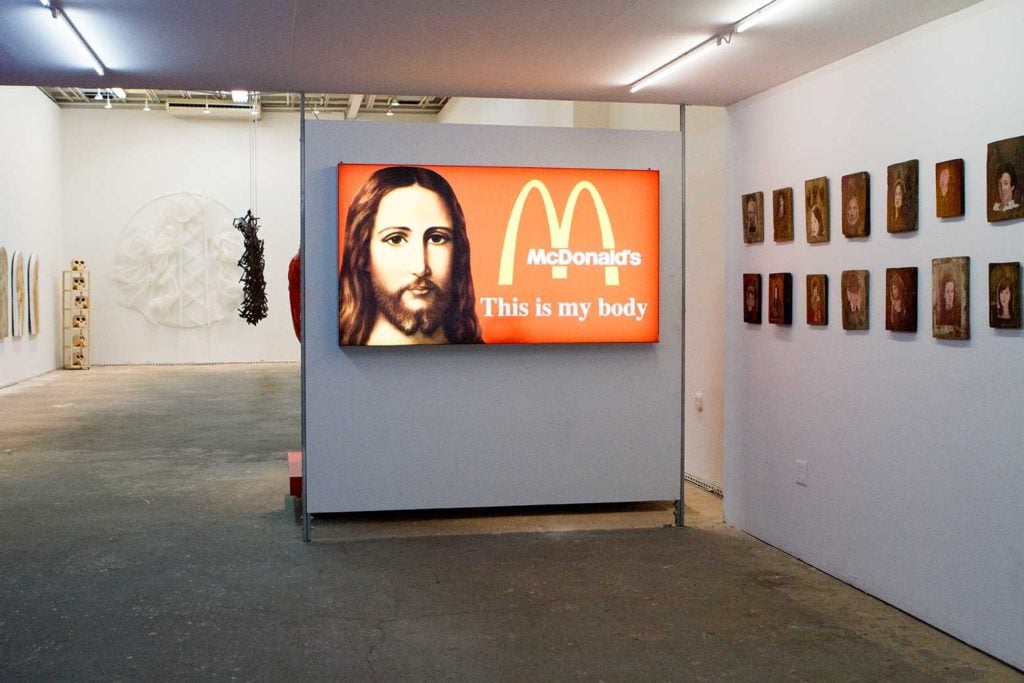

Installation view.

Photo: WhiteBox.

Alyokhina says the Russian government under Putin has employed religion—or rather, recycled it from its original form—as a means of controlling how citizens vote, dress, date, entertain themselves, and behave. “[We were told] true Christians would vote for Putin. That’s why we came to this cathedral [to perform]…You can rent a room in the bottom of this cathedral to have parties with music, with girls and stuff.,” she continues. “The price is on the official website!”

The concept of “recycling religion” came about by considering the relationship between Pop art and conspicuous consumption in America, and how this mirrors the role of religion in Russia.

“[Church] has become commercial—like a supermarket,” Guelman says.

Fittingly, we are standing beneath a giant Alexander Kosolapov sculpture that features a portrait of Jesus emblazoned atop a red Coca-Cola logo and the words “this is my blood.” In the other room, another Kosolapov work has the McDonald’s arches with “This is my body” underneath.

Installation view.

Photo: WhiteBox.

“In the media, in public spaces—a lot of people are just scared to say what they really are thinking. Because if you do it, you are going to prison,” Alyokhina says.

Hence the need, from her point of view, for Pussy Riot’s ethos to become part of a larger movement. With help from Guelman, Alyokhina and other Pussy Riot activists plan to open the New Balkan Women’s Museum in Montenegro: a featuring artwork by women from around the world. It will employ only female curators and administrators and show only female artists. A date is not yet set for the museum’s opening, and Alyokhina says she is still consulting with fellow feminists about how it should look.

Alyokhina is also working in Russia to protect political prisoners from abuse and offer them legal and financial aid—the auction that resulted in the closing of Guelman’s gallery was part of this project—as well as on the website MediaZona, a criminal justice media outlet she helped start in 2014 that focuses on courts, law enforcement, and the prison system in Russia.

I ask Alyokhina how she maintains the strength to do these things despite the dangers to her health and safety. She looks at me blankly, as if confused by the need to pose such a question.

“If you don’t have a sense of humor, you will die in Russia,” she says. “What they are doing, they are doing with serious faces. But the only [option] you have is just to give a smile and continue with what you are doing,” she says.

“Recycling Religion” is on view at WhiteBox until January 17, 2016.