Recently, when sorting through emails with offers from galleries, Alex D., an art collector with an interest in emerging artists, came across some images of work by Moritz Kraus, a minimalist painter, that piqued the buyer’s interest.

Kraus’s prices were good, and the artist was well regarded by a collector friend of Alex D.’s who owned another work. There wasn’t much about the artist online, but a tight-knit group of active Instagram users, all Italian art collectors, were hyping his work. Alex D. felt in the right mood and closed the deal. The painting arrived shortly thereafter.

There is nothing unusual about this. Shopping for art is, like other consumer pursuits, sometimes laborious and other times intuitive and quick. But what makes this different is that neither Kraus, nor the collectors who seemed to love him, actually exist.

Profile of Carlo Alberto Ferri.

Scam or Prank?

With its main arteries of business being not only wealth, but, more importantly, conspicuous displays of it, the art world leaves quite a bit of room for schemers and hucksters. In 2011, New York’s 165-year-old Knoedler gallery collapsed after it was revealed to have been a conduit for fake works by Abstract Expressionist stars.

The rise of social media introduced new problems. Less than 10 years later, Anna Delvey took advantage of a distracted, image-hungry art world and cunningly used Instagram to gain the trust of industry high-rollers and rack up credit card debts.

So it’s not a complete surprise that Kraus and his biggest boosters—a group of supposed art collectors including a Verona winegrower named Raffaele Sartori; a fashion entrepreneur called Beatrice Rinaldi; a young heir, Carlo Alberto Ferri; and Italian-born, Switzerland-based businessman Pier Paolo Lonati—never really existed. What’s surprising is the inventiveness of the ruse, and how quickly and easily a social media system of peer review managed to entrap real collectors.

While the Italian art world is teeming with gossip, it has not been confirmed who was behind the four accounts: one person, or a small group of people, appears to have created a network of artificial characters to boost the career—and sales figures—of a single imaginary artist, as well as at least one imaginary work by a real artist.

It matters that real money changed hands: two European collectors, including Alex D. (this is not their real name) confirmed to Artnet News that they bought works by Kraus for five-figure sums; in one case, it was after Ferri and Lonati made the suggestion through Instagram. According to price sheets shared by one of the collectors, Kraus’s paintings went for about €1,000 for small pieces, and up to €3,000 for larger canvases.

So was it just an insider art project aimed at showing the art world its shallowness? Or is this a case of out-and-out fraud and potential copyright infringement?

Into the Rabbit Hole

The elaborate, short-lived troll, which appears to have begun last summer, started to unravel in late 2021 when Milan dealer Federico Vavassori spotted what appeared to be an artwork by one of his artists on the Instagram account of a collector he did not know: Lonati, an Italian, Switzerland-based businessman.

Curious, Vavassori sent the image to his artist, who confirmed that it was his, but that it had been digitally manipulated. Combing Lonati’s profile for clues, Vavassori noticed a little network of collectors that seemed to know one another (Lonati, Sartori, Rinaldi, and Ferri) and who routinely replied, commented on, and liked each other’s posts. They wrote to emerging artists expressing interest in their work, and they even published interviews in the press.

Vavassori began to contact each individually and ask about their collections. It didn’t take long for whomever was behind the account to give up the scheme: the person admitted to Vavassori that the four collectors were not real, and that the accounts were all just a bit of “entertainment.” The accounts then disappeared.

Vavassori didn’t know it at the time, but pictured on those accounts’ social media pages were not only fake works by real artists, but also fake works by a fake artist: the supposed German painter by the name of Moritz Kraus, whose works were being pumped for a short time by this network of faux collectors.

Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

It’s All in the Image

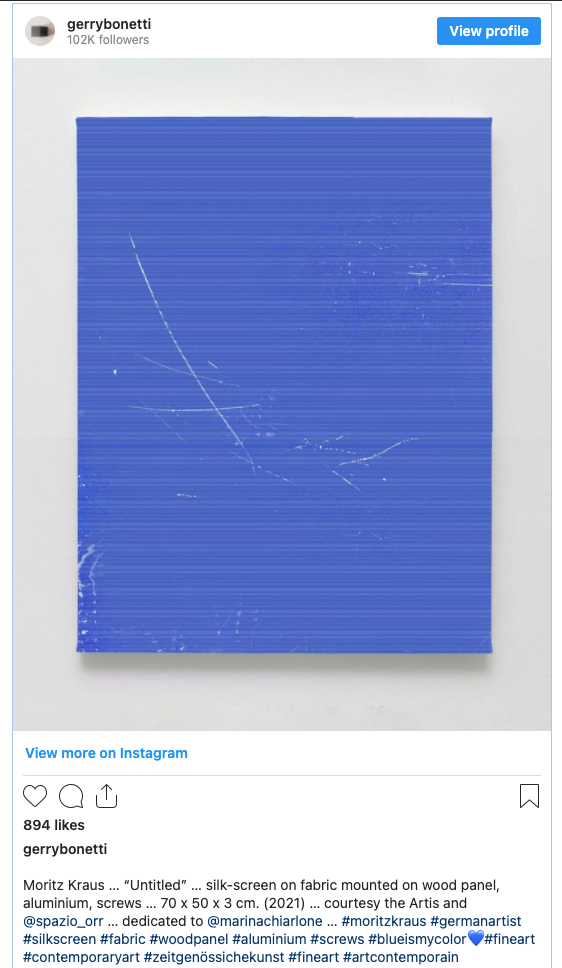

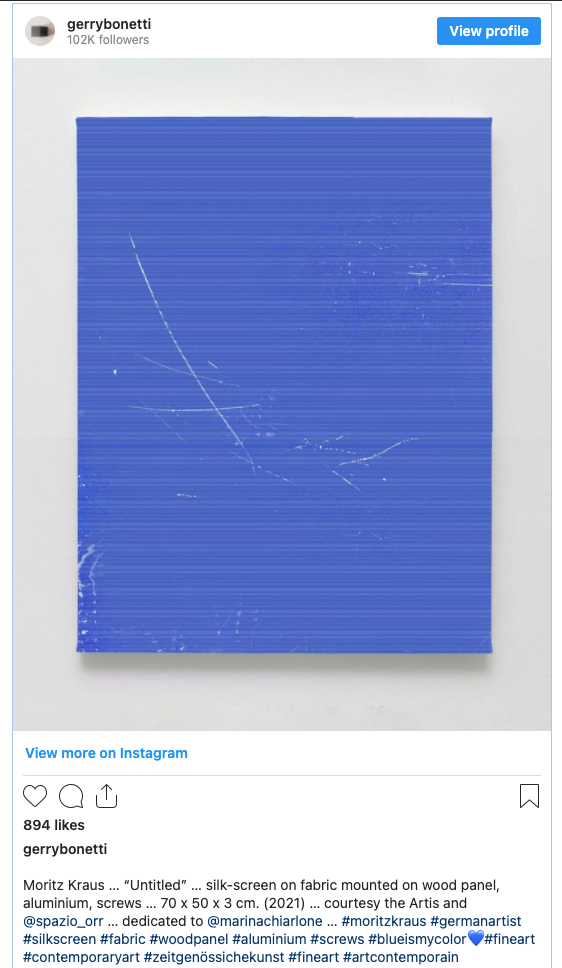

Even after the collectors’ Instagram accounts disappeared, it wasn’t hard to find images of Kraus’s silk-screened paintings or works on aluminum, all reminiscent of the zombie formalist wave of the 2010s. The artist, it seemed, also had a recent show at a venue called Lab Shimokitazawa, but, then again, that gallery may not exist. It appears to have no online presence, no physical address, nor any real exhibition history. (Conveniently, Shimokitazawa is the name of buzzy neighborhood in Tokyo, so it has the name equivalent of Lab Williamsburg.)

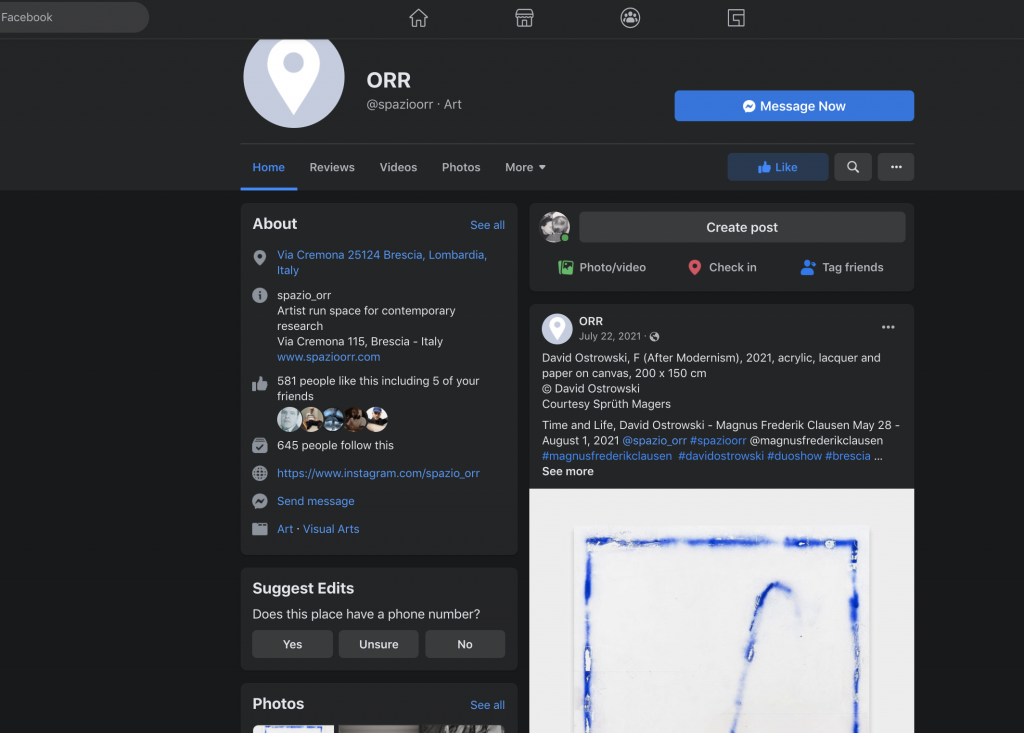

Yet Kraus did apparently have one show at a real-life venue: Spazio Orr, a space in Brescia that has worked in the past with artists such as David Ostrowski. Two of the collectors Artnet News spoke to had bought works by Kraus from the gallery. Yet the majority of the people who spoke to Artnet News, who had either done business with the space or collaborated with them, had never actually been there—strange in retrospect, but far from unusual for a globally stratified art world.

Whether the space still exists is unclear. Its website is down, and an upcoming show it had planned with Paul Czerlitzki was cancelled by the artist. But it did, at least once, have a real address, and was run by two artists: Federica Francesconi and Francesco de Prezzo. The pair frequently collaborated with up-and-coming curators, and participated in a few small art fairs. Their gallery opened in 2019 with a show titled “Champagne Taste on a Beer Budget.”

A work by Federica Francesconi at the Saito Private Art Collection, which has no online presence. Via ArtViewer.

There is an email address for Spazio Orr, barely retrievable via some meta data on Google. I sent the gallery a note, requesting confirmation on the sales of Kraus’s works.

I also asked if Francesconi would confirm details about her own recent art exhibition in Tokyo at the Saito Art Collection. Though it cropped up on Art Viewer (the page has now been deleted), an exhibition listing website that’s a favorite of artists, the Japanese collection itself has no trace of existing on the web or physically. Francesconi’s cloudy abstract paintings occur in grey hues, large canvases for extremely little content. The artist also seems to have purchased herself a full-page ad in the front pages of Mousse Magazine‘s January issue—unlike everything that was posted online, the latter was likely a gesture a little harder to undo.

I wondered, momentarily, if I was speaking into a void. But someone replied to my email rather quickly, suggesting I take a look at the text that accompanied the Saito Art Collection show. One line from the press release struck me in particular: “It is not an exaggeration … to think of the famous Schrodinger’s cat, the one that taught us that there is no stable and material reality that we simply accept, but that our gaze also determines the real.”

I pinged Spazio Orr’s email again: “Can we think of Moritz Kraus along the lines of Schrödinger’s cat?”

Back came a cryptic response with a slew of questions, some oddly worded. “Is it necessary to physically see a work of art to believe in its existence? Have you ever heard of the invisible cube by Gino de Dominicis? How much do you get influenced by the narrative of a work you have never seen?”

And then: “We don’t have any answers at the moment to these questions.”

A screenshot of what remains of Spazio Orr’s Facebook account.

The Same Way Back in

Which brings me back: scam or art project? And if it is an art project, is it any good?

Earlier this month, Milan lawyer Francesco Francica filed a claim with Italian authorities on behalf of Vavassori, the Milan dealer, asking them to investigate who is behind the accounts while pursuing damages for copyright infringement on behalf of his artist whose work popped up on a fake collector’s account.

Francica believes that laws have been broken. Yet for the most part, those looking from the outside in felt much more magnanimous.

“If it’s an art project, it is interesting to me,” said Aurélien Le Genissel, a Barcelona-based curator who wrote the referenced text for Francesconi’s fake show (Le Genissel said he had been contacted for the job over email by Francesconi who had seen images of his curatorial work on Instagram—he did not realize the exhibition in Tokyo did not exist). “It raises questions about the legitimization of art and artists on Instagram,” he added.

Even one of the duped collectors who bought a work by Kraus said it was a clever demonstration of “how easy it is to manipulate the art market. “Similar things happen all the time, and also higher up in the food chain,” the Europe-based art buyer said. “This was just a new way of doing it.” They even plan to keep the work because the story “makes [the work] more interesting.”

Lawyer Till Dunckle says that, legally, an artist can call themselves whatever they want. “So if the name ‘Moritz Kraus’ is only a fictitious designation for the true author, this is not only legally irrelevant, but also widespread,” he said. He said that use of a pseudonym by several, cooperating authors, however, could enter dubious legal ground because “a buyer will usually assume that the same author is always concealed behind ‘Moritz Kraus.'”

A screenshot of a work purportedly by Moritz Kraus on Instagram.

One thing, at least, seems plain: a couple years lived largely online is ripe ground for creative schemes that bend definitions of reality, especially when all us need to pump ourselves up once in a while.

If this whole thing is an art project, it isn’t a great one—it is rather the sum of a few tricks made on other individuals, which is deceitful, self-serving, and not entirely conceptual.

But it does reveal the fact that our behaviors and socializing habits on Instagram are a confidence trick, even as the platform grows in relevance for art dealers doing real business. Dealers, artists, and journalists, for that matter, are getting very used to DMs with all kinds of opportunities and “opportunities.” As we float off into this epoch of bored ape profile pics and cryptic usernames, let’s just not forget that we’ve been lying to ourselves and one another for quite some time now.

I went back to look at the text Le Genissel wrote about Francesconi, which, per his request, Francesconi removed from the internet. Instead, Francesconi has appended a new quote, one she attributes to the physicist and author Carlo Rovelli: “When we look around we are not really ‘observing’: we are rather dreaming of an image of the world based on what we knew.”