People

‘I Think I’m in an Abstract Relationship With Reality’: Farah Atassi Takes on Modernist Traditions at the Musée Picasso

Devorah Lauter

Farah Atassi is not entirely comfortable with you feeling comfortable about her artwork.

But when walking into the first room of her current exhibition at the Musée Picasso, the urge to take a deep, calming breath is strong.

Inspired by Picasso’s bathers—examples of which are on display at the show’s entrance—Atassi’s recent body of work centers on Modernist-inflected depictions of women posing for male artists throughout art history. At the center of her large canvases installed at the start of the show, curated by Florence Derieux, the women are rendered in geometric, simplified color swatches, and seem in peaceful harmony with their pastel surroundings—beaches, waves, and sun. Their eyes are closed, and all you want to do is to go there with them.

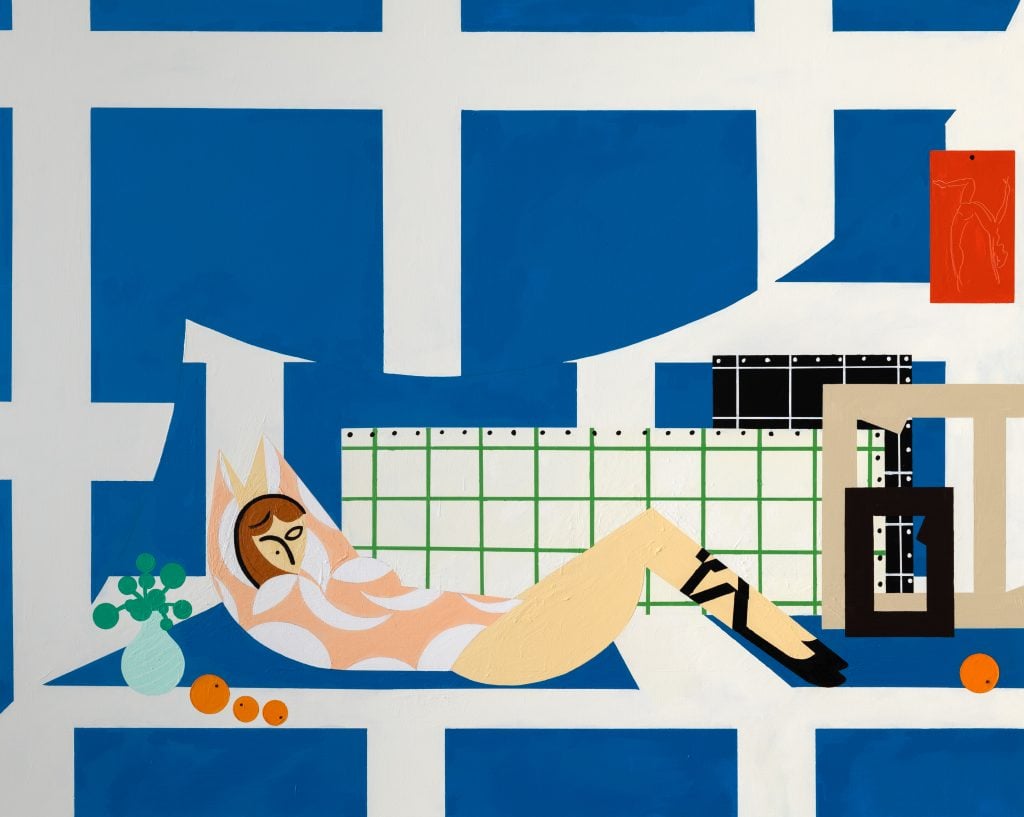

Farah Atassi, Resting Dancer in Blue Studio (2022). Photo: Matt Bohli.

Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

But “there is something that is not calm when you discover the whole exhibit,” noted the Syrian-born, Brussels-raised artist, speaking to Artnet over the telephone, because her Paris studio had just been emptied for the current show.

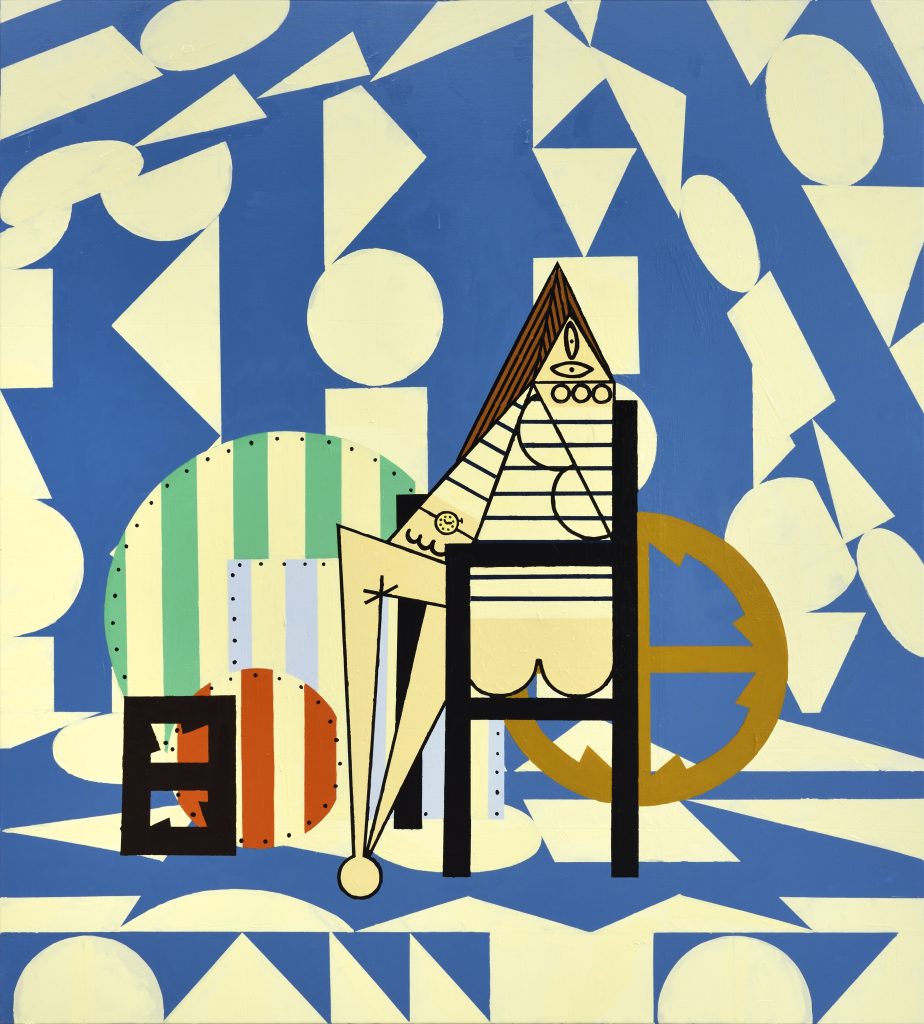

Indeed, across 15 paintings at the Musée Picasso, including some new ones, Atassi’s palette, subjects, and forms shift from room to room. Dancers begin to turn, wide-eyed—do they glare?—toward the viewer. In Model in Studio 2 (2019), the flattened, cubist figure of a woman with a triangle-shaped head, her eyes set perpendicularly and her nude, vector-like legs coming to a ball point, strikes with its strangeness and beauty. The figure is surrounded by the oversized, bright patterning that adds a layer of decorative splendor to many of Atassi’s canvases.

Farah Atassi, Resting Bathers (2022). Photo: Matt Bohli. Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

Atassi, 41, acknowledges that her artworks, which she describes as done in “the vocabulary of abstract painting, though I’m a figurative painter,” might give a soothing impression at first. Referring to Baudelaire’s famous refrain, “luxe, calme, et volupté” [luxury, calm and voluptuousness], Atassi sees a link to the 19th-century poetic verse—and just as in Flowers of Evil, Atassi uses a sense of surface wellbeing to draw us in one direction, only to twirl us in another. The visual beauty and color-packed punch of her paintings invite us to look further at the energy and strength of the almost otherworldly women depicted. Piercing, simplified shapes strike at or around them in an allover pattern that distorts normal perspective. Women may be at rest here, but they are surrounded by intensity, whether in abstract shapes, or figurative still lifes. The result is definitely more blood-pumping than relaxing.

“By putting myself in the position of these male artists who painted these women, but doing it myself in this abstract manner, I freed the model of the painter’s [sexual] desire for them, and I realized that the models gained an autonomy. Over time, they took their revenge,” she added.

Farah Atassi, Model in Studio 2 (2019). Photo: Matt Bohli. Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

In this show, “you can feel my restlessness… because my work evolves an enormous amount, and I am often questioning myself,” Atassi said. Early in her career, Atassi explored extremely simplified forms—building blocks, cubes—in an attempt to create “distance with the subject,” and illuminate forms of hierarchy within the work. “It was really about questions of anti-narrative, but the problem is that I realized narration is intrinsic to painting,” she said. So she expanded to still lifes, and eventually delved into the staged representation of women, and “the great story of painting, seen through art history.” “I refuse to be a painter who deploys a single, trademark style, and does variations of that their whole life… I’d be incredibly bored. I always try to go further, to renew and question things.”

Art lovers around the world are certainly not bored by the work. Acquiring an Atassi painting now is a real challenge. “I was there at the beginning, when it cost €3,000 for a painting, about 10 years ago. Today it costs [around] €50,000, and there are no available paintings,” said Renos Xippas, whose eponymous gallery first represented Atassi. Today, she is also represented by Almine Rech (who is married to Picasso’s grandson) and François Ghebaly. Xippas doesn’t like to keep formal waiting lists, but said he gets regular calls from clients who ask if they can acquire a work—and he inevitably has to keep them waiting.

Xippas first saw Atassi’s work when his director at the time, François Quintant, showed him images on his phone, right after visiting the artist’s studio. Xippas immediately insisted they go back to her studio together. “I said, ‘François, we’re getting in a cab and going,’” Xippas recalled. “I was astounded. It had been a long time since I’d seen such an interesting language… I understood this is a woman who doesn’t have a limit to her creativity.”

Xippas noted then how Atassi had used tape to structure grids on her canvases—a technique she still employs—which acts as the foundation of her compositions. “She does preparatory sketches with the tape, right on the canvas,” which she can move around. “It can give the impression that she may have messed up, or painted over something, but not at all. The tape creates several different layers,” he explained.

Works in Atassi’s studio. Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

Seeing the physical layers of paint is important to Atassi, who regrets that digital representations can “create a misunderstanding” about her work, making it appear flatter than it is. “My paintings are really about the material, and a reminder that this is painting and not imagery. It allows me to invite the viewer in,” she said.

Atassi was introduced to painting while growing up in Belgium, where her parents (who did not work in the arts) took her to museums. “I really went nuts when I saw the paintings. I felt exalted in front of the large paintings by masters,” she said. By age 13 she had a little studio in her home, and she was painting with oil. “I always wanted to be a painter. It was obvious,” she said.

Art school was also a clear choice. She attended the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as part of an exchange program with the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and completed her schooling at the same institutions under the tutelage of artist Jean-Michel Alberola in Paris.

Works in Atassi’s studio. Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

Passionate about modern artists such as Manet, Ingres, Matisse, and of course Picasso, Atassi pores through art history books for inspiration. Then, via her works, “I replay the great themes of painting in the studio,” she said, adding, “I display these sources, and even question them.” That is particularly the case in her exploration of the relationship between models and painters. Along with rendering her subjects almost abstract and artificial, Atassi said she “stages” the relationship in her works to help question the “fundamentals of painting.”

“I think I’m in an abstract relationship with reality,” she said, noting how even her play with figuration itself has a “fiber of abstract painting.” She feels the narrative aspect of her work is “intrinsic” to her paintings—and all painting—but “in the end, what interests me are formal questions… I’m not inspired by what is real. My sources are other works of art.”

Atassi’s fascination with the modern artists mentioned above is central to her practice, and it is also why the women she depicts all appear to be of Caucasian background—even though Atassi herself is Syrian, and as she puts it, “not exactly a white woman.”

“I’m painting Occidental women who have passed through the history of painting,” she said. “Formally speaking, I haven’t been able to leave behind this pink [of the subjects’ skin color]. If I paint black women right now, it will necessarily have a political connotation, which wouldn’t bother me in itself… but it’s something I need to work through,” she added.

Farah Atassi, Dancer in Rocking Chair (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.

The artist is currently working on a series that focuses on Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe, and the half-turned posture of its central figure. With her work placed in several international institutions early in her career, in addition to the current Musée Picasso exhibition, and she will be featured with Ulla von Brandenburg at the Fondation Pernod Ricard in Paris in 2024, along with exhibitions at her galleries in the coming months.

Atassi “is certainly strong. She dares to confront herself with major modern artists such as Matisse and Picasso,” her gallerist Almine Rech told Artnet News. “Many collectors who know art history and have intergenerational works in their collections wanted her work very soon. Now different types of collectors have come in, from Europe, the U.S., and Asia. Her success keeps growing.”

And along with it, her art.