Up Next

Felix Beaudry’s Knitted Grotesqueries and Disembodied Heads

The textile artist's distinctive creatures are infiltrating the art world—one gargantuan at a time.

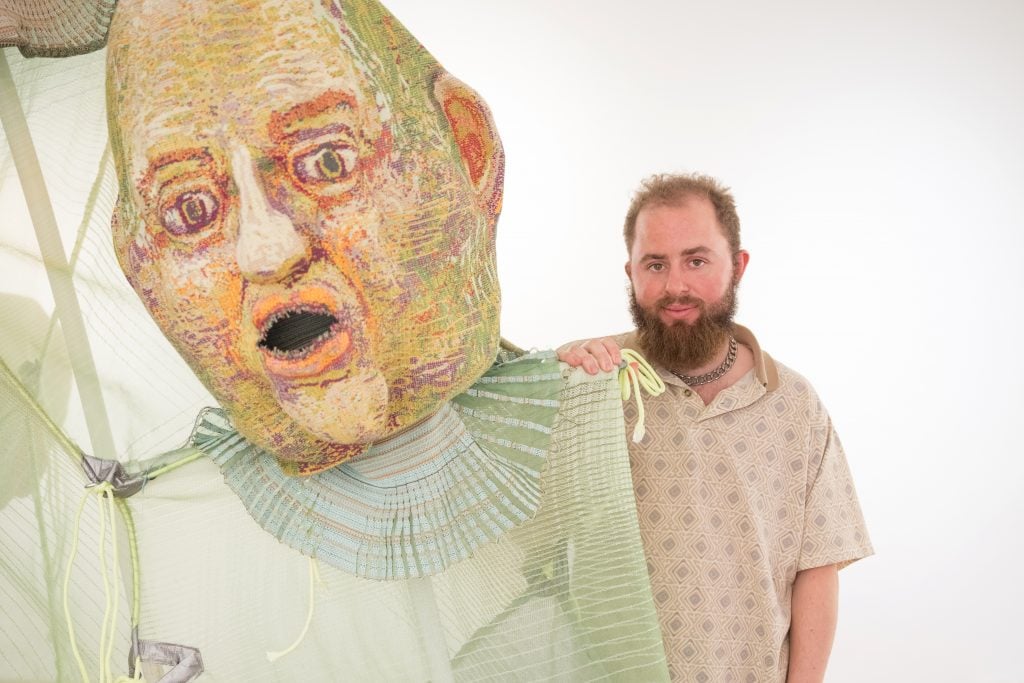

On a chilly sunny day last week, Felix Beaudry was surrounded by an array of his gargantuan body parts. “I sort of have a narrative to these people,” the 27-year-old artist explained of these plush, knitted sculptures, “but then a lot of it comes from the way I’ve always just been drawn to old dudes and love old dude bods. This is just what comes out.”

Beaudry, scruffy and wearing a thrifted polo shirt, was taking a break from installing his two-level exhibition, “Tender Spawn,” which runs through June 8 at A Hug From The Art World, a gallery in a former carriage house in New York’s West Chelsea. Beaudry’s giant disembodied heads were strewn about, some sideways on the floor, others creepily peeked out like gargoyles from the ceiling rafters. On the second level, limp, floppy arms extended from the ceiling like tendrils.

The main attraction is an installation that depicts a kind of bisected, multi-headed hulking humanoid Colossus called Emerge, Crest, Swash. A green net carcass reveals PVC pipe bones and knitted innards.

Felix Beaudry sitting amongst his sculptures. Photo by Elvin Tavarez.

“The central thrust of it is thinking of the fabric as the separation between the physical body and the mental experience—and thinking about fabric, specifically clothing, as signifiers of representation of your personality or these different modes of being,” Beaudry explained. “Fabric is an extension of the skin in a way that confuses what is internal and what is external, or how you can control how you’re seen.”

Beaudry’s main tool is an industrial knitting machine that he imported from Germany (he had to hire a rigger to hot-wire it to work with American wattage). He programs it with drawings. “What comes out of the machine is often pretty unexpected,” he said. Beaudry showed me beautiful collages of himself, nude, balletic, and stylized in a pile, that were used to compose this exhibition. It’s fascinating to see this step in his process and they’re worthy of display.

Felix Beaudry, Emerge, Crest, Swash. (2024). Courtesy of A Hug From the Art World.

Beaudry certainly has an aesthetic and an immediately recognizable visual language, but mainstream beauty isn’t in his vernacular, nor is he fussed to incorporate it. He developed his perspective early, and asserts it was partially inherited.

“My mom’s a painter and she has always exaggerated certain things about people’s faces, mostly wanting to represent them as they are,” Beaudry said. “Growing up around that, you gain this huge appreciation. Things can become so much more beautiful—like people’s weird skin problems or fat rolls look so amazing when they’re painted. I’d be like, ‘Oh, you could paint her, she’s super pretty.’ She’d respond, ‘There’s nothing to look at on her face.’ That definitely informed a lot about the way I want to represent people.”

Felix Beaudry’s disembodied heads are like gargoyles in the gallery rafters. Courtesy of A Hug From the Art World.

Adam Cohen, the founder of A Hug From the Art World, discovered Beaudry in 2023 when he saw his solo show at the Lower East Side gallery Situations that was centered around The Glob Mother and Lazy Boy, two behemoths splayed atop a truly hideous 1970s floral sofa. “I was obsessed,” recalled Cohen, a former director at Gagosian. “I knew it was amazing. I was looking for a Valentine’s Day gift for my wife, and I ended up buying her a severed head. She was a little confused that that was a Valentine’s gift, but it sits on my coffee table.” Beaudry will have another exhibition at Situations, a gallery on Henry Street, early next year.

Beaudry has had a slow burn New York art world ascent. He studied at RISD and was originally focused on ceramics (he specialized in heads as well) before shifting to textiles, a medium that he has never turned back from. I kept stumbling across his strikingly bizarre work at group shows over the past year at Marianne Boesky Gallery and at Club Rhubarb’s temporary Lower East Side space. His misshapen forms spoke to me—they were funny, jarring, and rather regal in their own way, and they clearly had much more to say than just shock value and had no horror undertones. They were like Grade A Southern Gothic grotesques, Flannery O’Connor-calibre anti-heroes, just aesthetically challenged, heads held high, albeit a tad droopy and oversized.

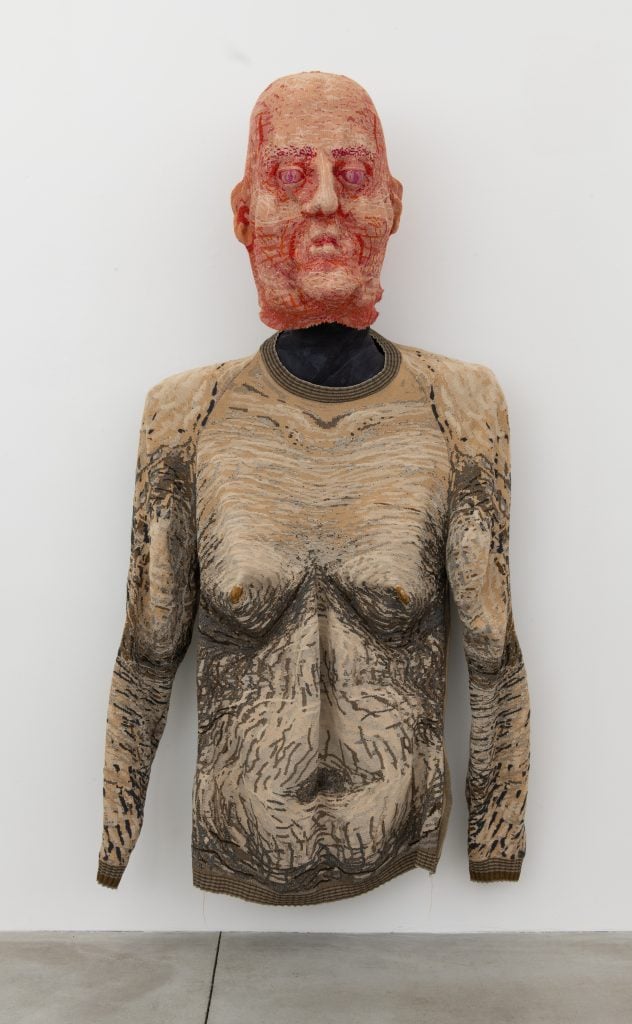

At the gallery Kravets Wehby, he proffered a show-stealing artwork of a drooping, undulating golem with pendulous man breasts—it worked as both a 3D wall hanging and a massive, wearable sweater. There was also a nude portrait of him (sewing stitches on a fetal pig) in his friend Linus Borgo’s knockout solo show at Yossi Milos. It was a contemplative, yet creepy, allusion to Roman mythology and fortune-telling and also a proud display of a trans body.

Felix Beaudry, Hollow Body (2023). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

Since Beaudry specializes in depicting, distorting, and rendering bodies as clothing, the transience of the mortal shell, I queried if his art was also a way to navigate his trans journey and pontificate upon it. “It’s definitely connected to that,” Beaudry said. “Leading back into the transness of it all, it’s taking things out of the paradigm of what’s mainstream sexually attractive or aesthetically pleasing.”

Beaudry, who grew up in Berkley, California, transitioned when he was 15. “People were familiar with the concept, it was 2012. It was before the shift in 2016 with Caitlyn Jenner or whatever,” he said. “I’ve always gotten along with teachers and my parents. It became me and my parents driving to therapy and then crying and talking all night or meeting with my teachers one-on-one and discussing what I need and my gender stuff. People were interested in my subjective experience, but it was also paired with what was more freakish. It was kind of like, you’re the only person like this. ‘What’s that like?’”

Felix Beaudry, The Glob Mother and Lazy Boy (2023). Courtesy of Situations.

This dichotomy is encapsulated in the work. “It is both feeling like a freak and the tension between learning to accept parts of your body and then also knowing that you can change them, kind of like clothes,” Beaudry said. “It’s that back and forth, wanting to inhabit so many different types of bodies as an experience. But also thinking about your body as an expression of who you are inside. I do think about the ‘man trapped in a woman’s body’ narrative a lot. It doesn’t make any sense to me, but I think at the same time it’s one of those things that I don’t have a good comeback for. It could be a very helpful metaphor, but there’s the urge behind it to prove, ‘this is who you and there’s a man underneath there.'”

Felix Beaudry holding up a head sculpture. Photo by Elvin Tavarez.

Beaudry tries not to overanalyze. “I love representational genitals,” he mused, “the folds of a vagina are amazing to make in fabric. When I started taking testosterone, mine changed. They’re so malleable, there is also a spectrum between genitals.” Beaudry’s work, which is soft, tactile, and pliable, contends that we’re all just souls housed in animated sweaters at the end of the day. Some are just more colorful and patterned than others.

From his home in upstate New York, he is continuing to work at his knitting machine daily, but he’s also been plotting his next art foray, which may be performance art. “This feels to me like it’s on its way to performance already,” he said of his sculptural installations. “I like the combination of the body and the fabric together. Seeing this stuff on people and seeing it moving is really exciting to me.” He added, “I’ve been thinking of incremental movements becoming a pattern, sort of like a dance, a pattern that circles back in on itself.”