People

‘There Is So Much More to See if We Are Brave Enough:’ Firelei Báez on Mining Memory, Myth, and Colonial Archives

The Brooklyn-based artist’s first European exhibition is open in Denmark.

The Brooklyn-based artist’s first European exhibition is open in Denmark.

Anna Sansom

When Firelei Báez was a visual arts fellow at the American Academy in Rome (2021-22), she went on a trip to Puglia, where she had a powerful dream. The Dominican Republic-born, Brooklyn-based artist recalls waking up with “almost happy” tears. “It was a dream of being moored at sea and this feathered creature, which seemed very ancient and that I can never figure out how to properly depict, was essentially rescuing me with expanded wings, [saying] ‘I will never abandon you at sea again’,” the artist said. “The reason that I woke up with happy tears was because the dream didn’t seem directed at me but at all my ancestors who crossed the Atlantic Ocean willingly and unwillingly.”

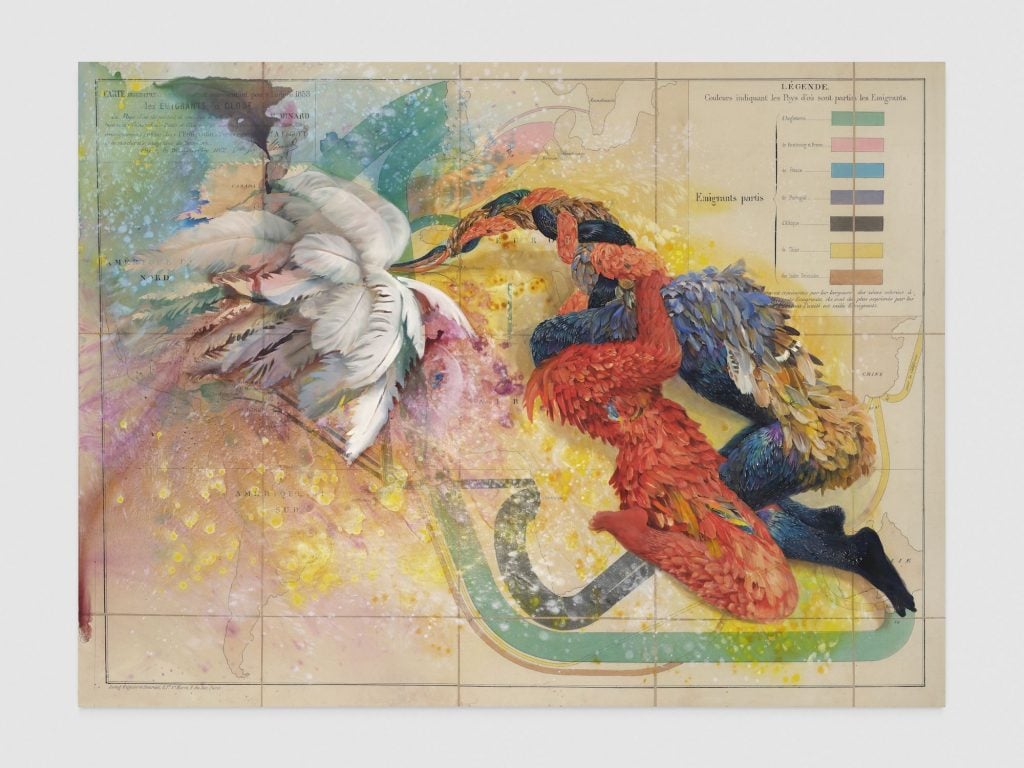

The poignant memory inspired a painting, A taxonomy for tenderness (Carte figurative et approximative représentant pour l’année 1858 les émigrants du globe) (2023), which is on view in Báez’s first European exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek, Denmark (“Trust Memory Over History”, through February 18, 2024). The entrancing artwork features two intertwined chimera figures, one festooned in scarlet feathers, the other in dark blue plumage, both with human feet and coiled, birdlike heads.

Firelei Báez, A taxonomy for tenderness (Carte figurative et approximatiive représentant pour l’année 1858 les émigrants du globe) (2023). Photo: Jackie Furtado © Firelei Báez

The painting is rich in cultural references. The sense of vibration conveys murmurations of birds, while the vivid colors bring to mind artists like Gustav Klimt. “I was looking at the work of Giacomo Balla, Klimt, and Hilma af Klint, and thinking about how color almost becomes a way of depicting an interiority that is so boundless that it can become the cosmos, and so sensuous that it’s all encompassing,” Báez explained.

The feathers allude to the manto Tupinambá, a ceremonial cape woven with red ibis feathers that was made by Brazil’s Tupinambá Indigenous people. There are believed to be only 11 such mantles in the world, all of which are in European museums, having been taken during the colonial era.

The National Museum of Denmark decided earlier this year to donate one of its five capes to the National Museum of Brazil, following a request from Tupinambá leaders and the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro. Báez excitedly recounted this repatriation, and how the cape had been portrayed in western art. “If you think of Max Ernst’s The Robing of the Bride (1940), you almost see his configuration of an original 15th-century illustration,” she said.

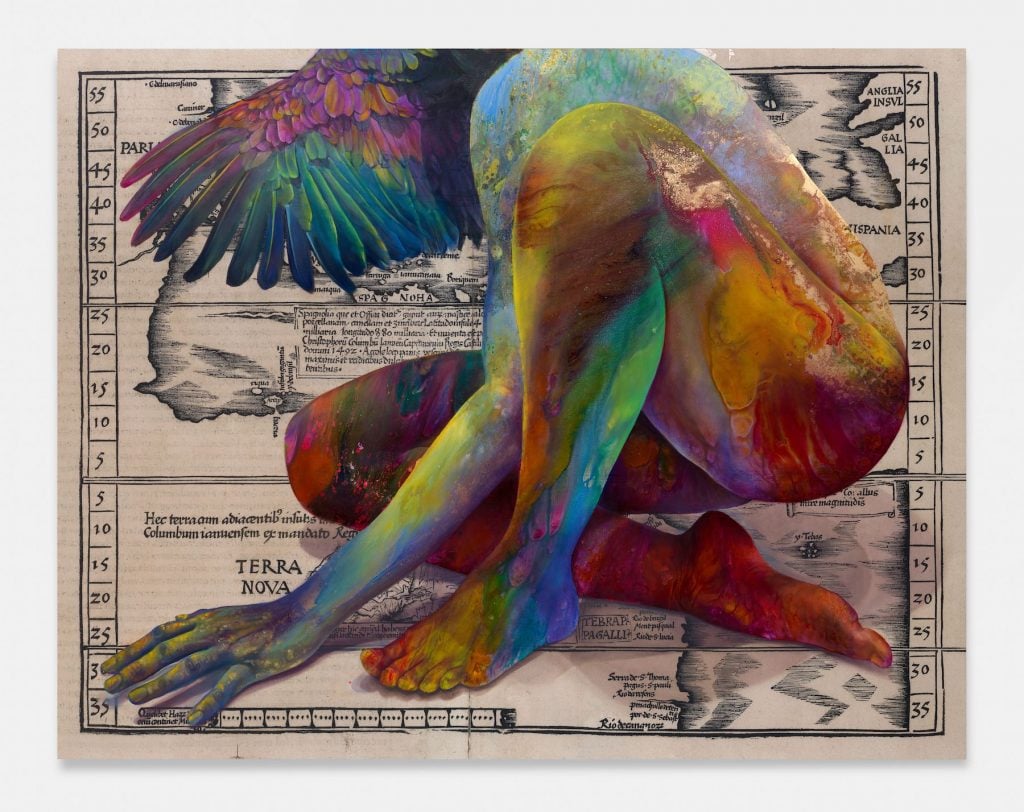

Firelei Báez, A Structure of Feeling (2023). Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo: Mats Nordman © Firelei Báez

There’s something disquieting about the work, too. Báez, who often refers to colonial archives, painted over a reproduction of a map dating from 1858, a decade after the abolition of slavery in France. It included color codes indicating the countries from which emigrants had departed. “This map is meant to be very scientific and factual, but it has one big glaring omission: my whole island of Hispaniola is outright missing from it,” Báez lamented.

Born in 1981 in the city of Santiago de los Caballeros, Báez moved with her family to Miami as a child. She attained an MFA from Hunter College and a BFA from Cooper Union. In the last few years, she has had a solo show at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, exhibited a monumental installation at Boston’s ICA Watershed, been nominated for the 2017 Future Generation Art Prize awarded by Ukraine’s Victor Pinchuk Foundation, and participated in the Berlin Biennale in 2018 and the Venice Biennale in 2022. This fall, she joined the gallery Hauser & Wirth

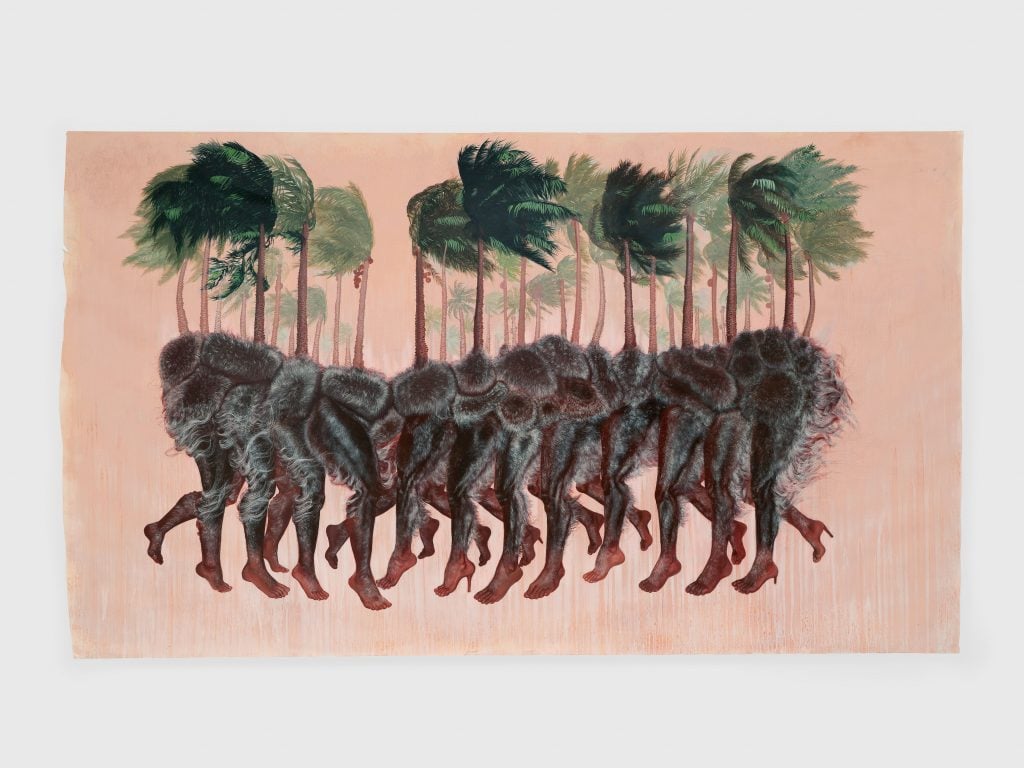

Firelei Báez, Years of holding your tongue (2018). Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Photo: John Lusis © Firelei Báez

It was in Berlin that Báez’s work attracted the attention of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and Germany’s Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. Her wall installation, Those who would douse it (it does not disturb me to accept that there are places where my identity is obscure to me, and the fact that it amazes you does not mean I relinquish it) (2018), consisted of book pages sourced from archival material on which she made intricate miniature paintings. Several colonial maps were adorned with hybrid creatures merging elements of femininity, flora and fauna. The Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg acquired the piece and will host the Louisiana show from June 22, 2024, through September 29, 2024.

“Báez’s artistic realm thrives on opposites and ambiguities, intertwining beauty with violence, personal perspectives with grand historical narratives and Caribbean mythology with science fiction,” said Mathias Ussing Seeberg, who curated the exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. “Rather than replacing truth with fiction or maps with myth, her work advocates for a multi-layered complexity of fictions that collectively shape our world.”

Firelei Báez, How to slip out of your body quietly (2018). Collection of Alyssa and Gregory Shannon, Texas. Photo: John Lusis © Firelei Báez

Another recurring subject in this show is the Ciguapa. Growing up, Báez would listen, enraptured, to her grandmother and mother telling stories about the mythical figure that represents a fusion of human, animal, and plant characteristics. Works such as Years of holding your tongue (2018) and How to slip out of your body quietly (2018) depict bodies sprouting palm trees and covered in twisted buns of straightened black hair.

“One of the things that I loved about that myth was that the Ciguapa’s feet were backwards; if you followed her footsteps, you were going in the wrong direction,” Báez recollected. “I think of the myths as psychic safeguards, little trapdoors or escape routes for how to navigate the world.”

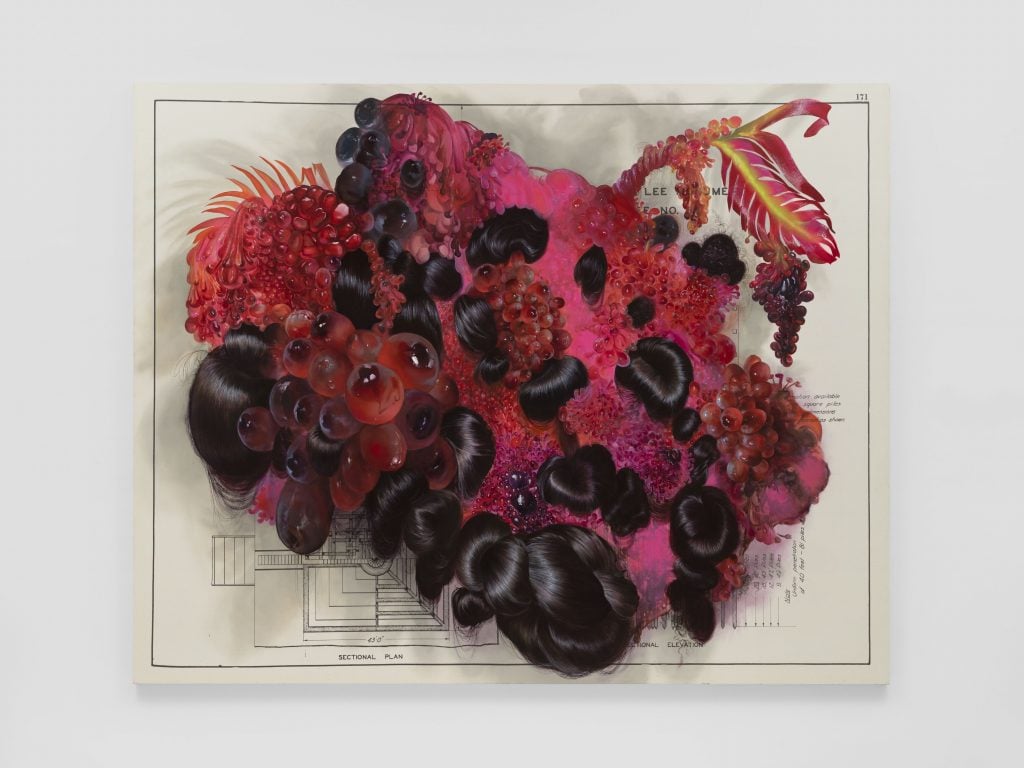

In Fruta Fina, Fruta Estrańa (Lee Monument), (2022), the same buns protrude from an abundance of succulent red grapes and other pink and purple fruits. The painting obscures a reproduced diagram of a Confederate statue honoring general Robert E. Lee, which was erected in New Orleans in 1884 and removed in 2017. The title recalling the “strange fruit” of Billie Holiday’s famed protest song, the work is an allusion to the lynchings of Black Americans. It also references the pressure for women across the Black diaspora to transform their hair “for the sake of respectability”. The shiny locks are a recurring element in Báez’s work: “Out of all the things that I paint, it’s something that’s very immediate and almost meditative to create,” she said.

Firelei Báez, Fruta Fina, Fruta Estrańa (Lee Monument) (2022). Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Donated by the Kotzubei-Beckmann Family Philanthropic Fund. Photo: Jackie Furtado © Firelei Báez

The exhibition offers a generous overview of Báez’s painting. What’s not included is her large-scale sculptures. These will feature in a show at the ICA Boston (April 4–September 2, 2024). Among other works, it will present pieces revisiting the history of Haiti’s Palace of Sans Souci which once served as the residence of Henri Christophe, who proclaimed himself King Henri I after fighting as a general in the Haitian Revolution. One of Báez’s installations reimagined the earthquake-damaged palace as a submerged archaeological ruin bearing West African indigo print motifs and women’s belongings embedded in algae. It referred to how some enslaved Africans were thrown overboard during the Middle Passage.

“Firelei Báez offers a view of history through multiple lenses, shifting perspectives and creating layers of complexity when history has only provided us with a single perspective,” Eva Respini, former Barbara Lee chief curator at the ICA, said.

For Báez, this is a promising time for diasporic artists to be expressing themselves. “A lot of archives, especially for peoples from the Black trans-Atlantic Middle Passage, are non-existent, but you have to build out of the positive and negative space,” she asserted. “Having the gift to be able to do that [means this] is such an exciting time, despite some of the horrific things that we have to go through. In so many fields, we have the very clear signal that there is so much more to see if we are brave enough. We can walk through certain doorways and see the world fully rounded and blessed into something new. And this is a potential that I’m always looking for when I make work.”

More Trending Stories:

Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets Into an Online Skirmish With A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol

Your Go-To Guide to All the Fairs You Can’t Miss During Miami Art Week 2023

The Old Masters of Comedy: See the Hidden Jokes in 5 Dutch Artworks

David Hockney Lights Up London’s Battersea Power Station With Animated Christmas Trees

On Edge Before Miami Basel, the Art World Is Bracing for ‘the Question’

Thieves Stole More Than $1 Million Worth of Parts From an Anselm Kiefer Sculpture