When Florine Stettheimer died in 1944, at the age of 72, the New York artist, poet, and salonnière, was still putting the final touches on The Cathedrals of Art, the last in a series of four monumental paintings devoted to New York’s cultural, social, and economic temples. Identical in scale, each painting measures five feet tall by just over four feet wide.

The series, which includes The Cathedrals of Broadway (1929), The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (1931), and The Cathedrals of Wall Street (1939), was a winkingly aware homage to places of worship in the city she’d called home for all her adult life. For the deeply private artist, The Cathedrals of Art is arguably the most personal of the works.

Though not critically adored in her lifetime, Stettheimer was fully enmeshed in the city’s cultural milieu and counted Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Stieglitz, and Georgia O’Keeffe among her dearest friends and frequent house guests. (Duchamp organized a posthumous 1946 retrospective of Stettheimer’s work at MoMA, the museum’s first dedicated to a woman.)

Peter A. Juley & Son, Florine Stettheimer (circa 1917–20). © Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Painted in Stettheimer’s quintessentially, and intentionally, feminine palette of whites, pinks, and reds, The Cathedrals of Art is a fantastical portrait of three of the city’s major museums—the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art—and abounds with depictions of real-life art critics, dealers, and even the artist herself, on the lower left, seeming to welcome viewers into the spectacular scene. One of the most famous of Stettheimer’s canvases, The Cathedrals of Art’s whimsical, even fey, atmosphere is a veneer for the artist’s incisive social commentary and informed contemporary perspectives.

Here are three facts about The Cathedrals of Art that might make you see the painting in a whole new way.

The Painting Is a Who’s Who of the New York Art World

Stettheimer’s self-portrait in The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In her lifetime, Stettheimer’s work was largely understood as ornamental, insular in subject matter, and, in the best cases, cultivating an American Symbolist tradition. In the past several decades, however, historians have underscored the satirical, even socially inspired, messages coded in her faux-naif style. (Stettheimer was something of a late artistic bloomer and worked in an academic tradition before finding her signature style of painting when she was in her 40s).

The “Cathedrals” paintings are unique for Stettheimer in that the subject matter isn’t overtly personal. Usually, her subject matter centered on the intimate world of her friends and family, including her sisters Ettie and Carrie. “The social character of these works is of a very private kind,” wrote art historian Linda Nochlin. “The sitters are the privileged denizens of a most exclusive world, the world of the Stettheimers’ entertainments, soirées, and picnics.”

The Cathedrals of Art presented a unique opportunity for Stettheimer to place the art-world figures she knew in real life into the fantastical conglomeration of the Met (center), MoMA (left, with references to paintings by Picasso and Henri Rousseau), and the Whitney (right), presented in a seemingly continuous stage-like setting.

Detail of The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum.

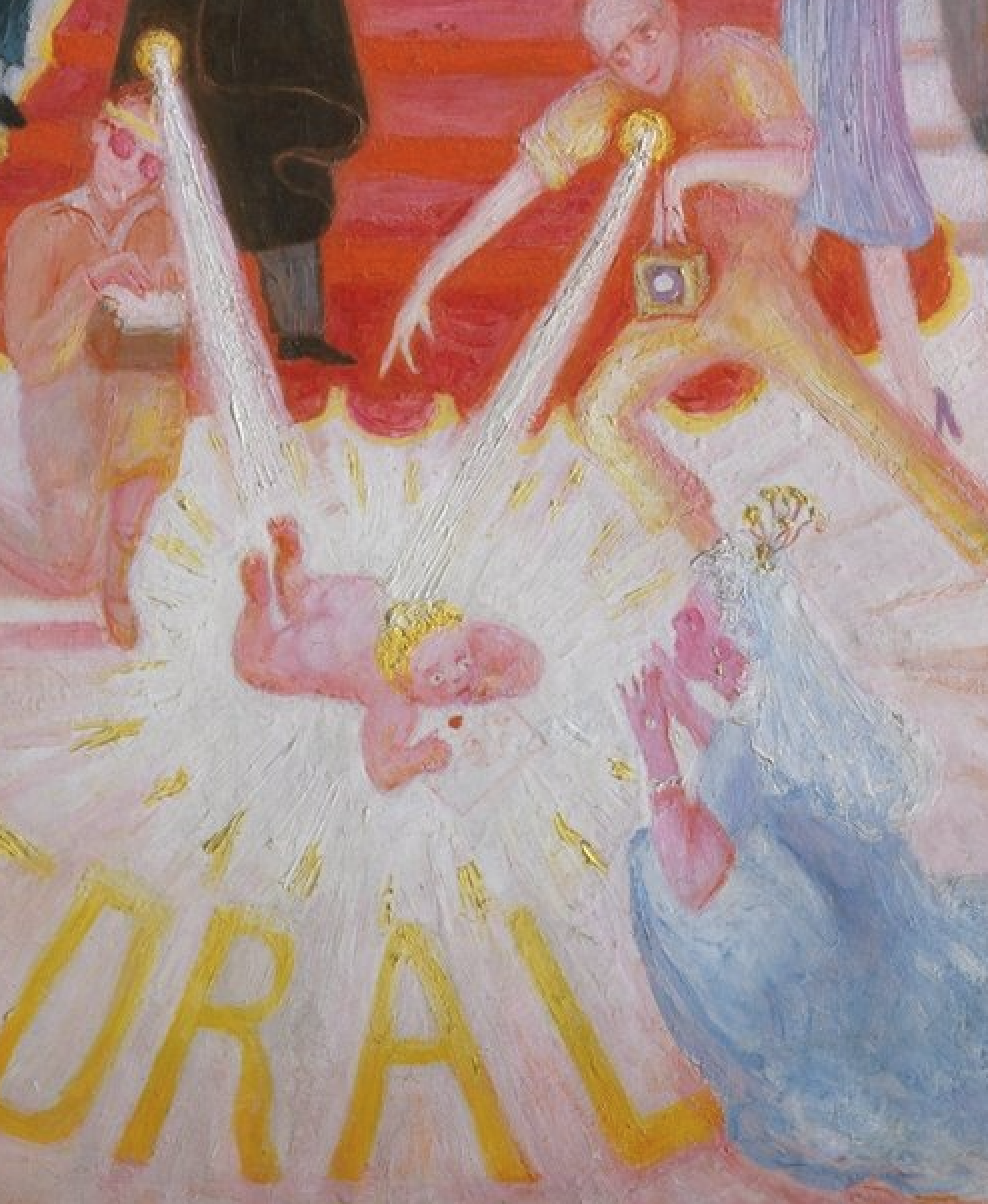

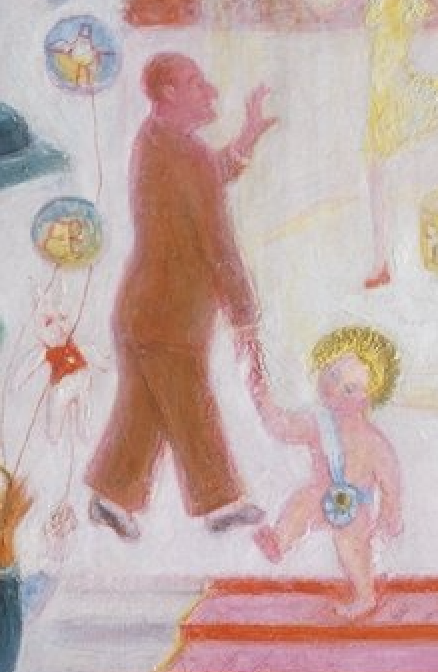

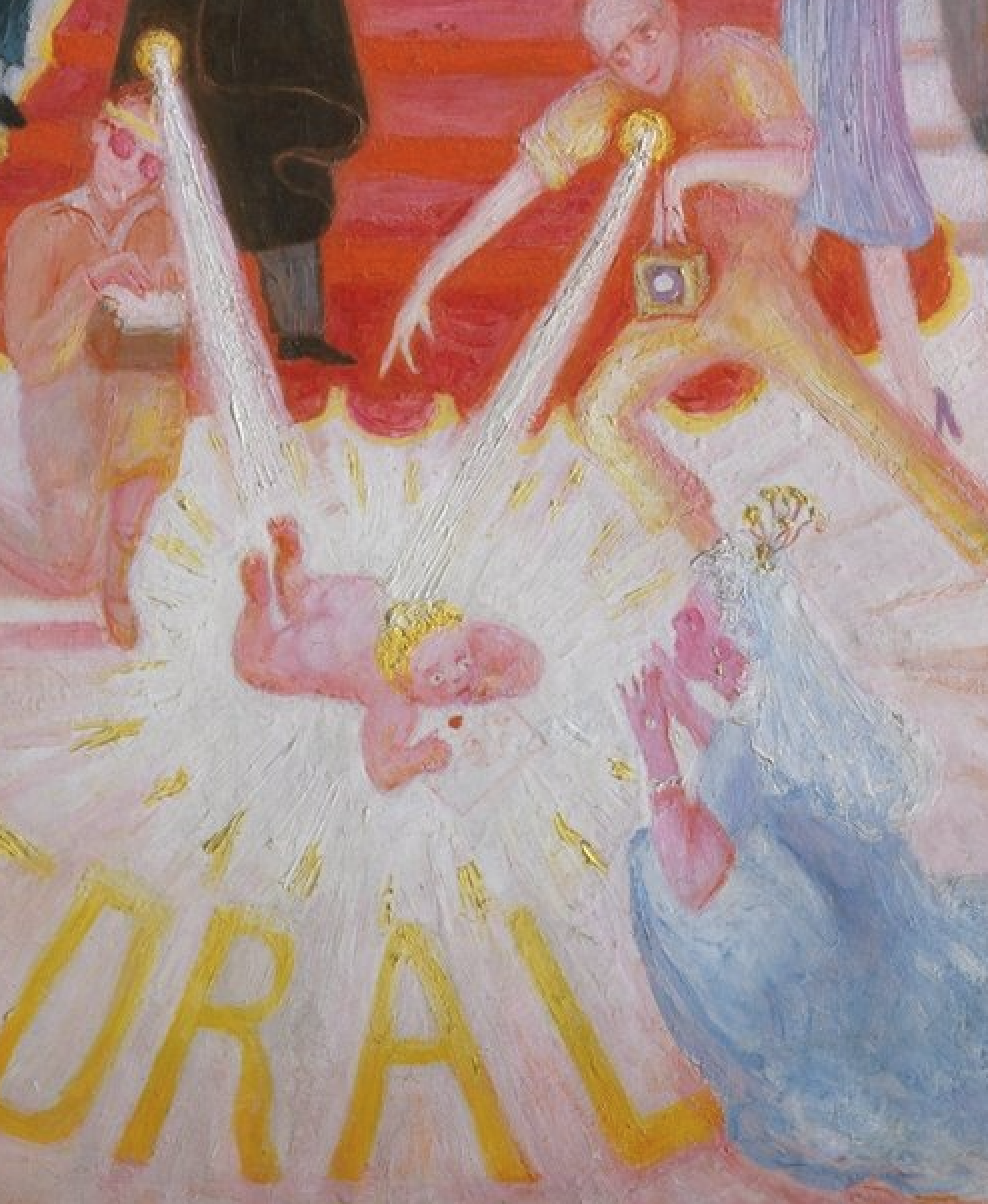

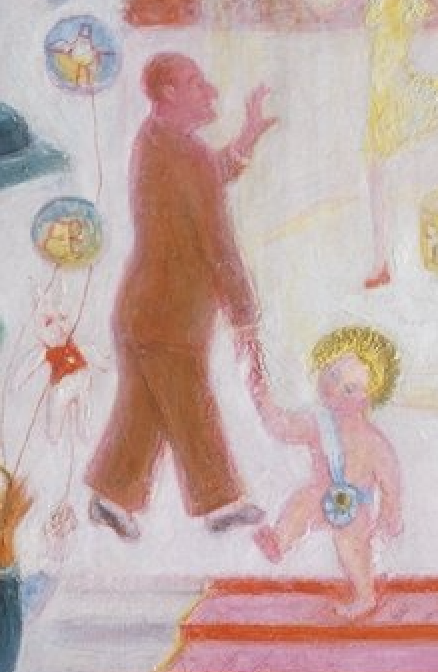

Famous figures abound In the work. Art critic Henry McBride is pictured toward the front of the painting with “stop” and “go” flags in hand—a reference to his critical powers. Alfred Stieglitz stands toward the center of the canvas in a dashing black cape that signals his role as an aesthete. The photographer George Platt Lynes is shown photographing a baby, which Stettheimer referred to as “Baby Art.” Museum directors are dotted throughout: Alfred Barr of MoMA appears seated in a Corbusier-style chair at left and the Met’s then-director Francis Henry Taylor walks hand-in-hand with a baby toward famous objects from the museum collection, as though on a tour.

Detail of The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

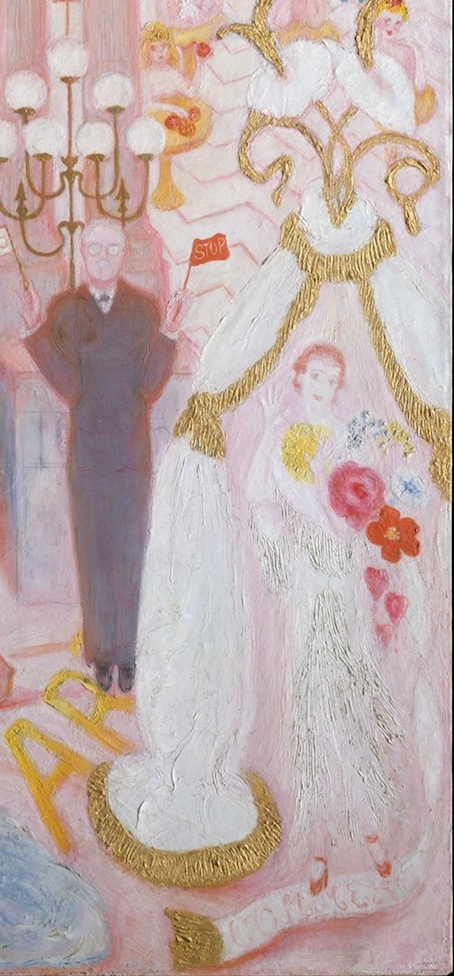

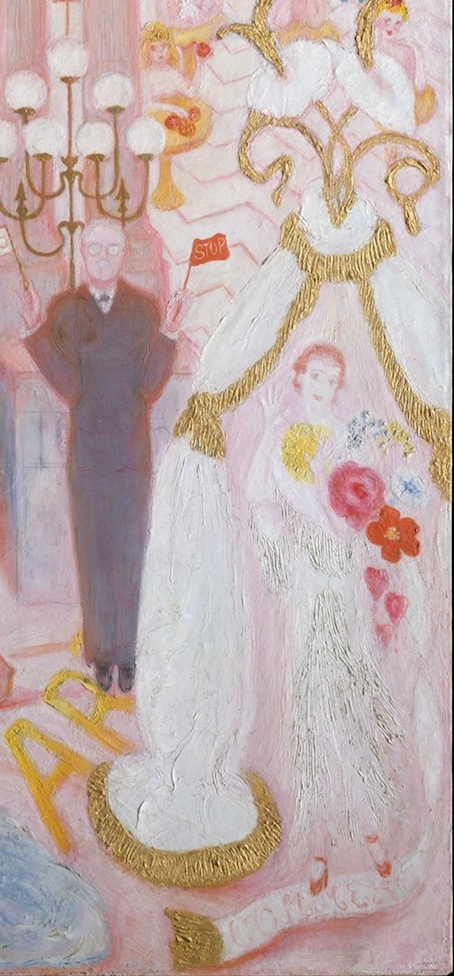

Women, usually central to Stettheimer’s painted worlds, exist mainly on the periphery of this scene. Stettheimer depicts herself, quite youthfully considering she was in her 70s at the time, labeled on the canvas as a commere, or godmother, of the scene. But she appears as an outside observer, residing in a canopied space. Similarly, Whitney director Juliana Force appears isolated, looking somewhat resolute beside a golden statue of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, at the back right of the painting.

Detail of The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As is typical of Stettheimer’s work, a puzzle-like arrangement of clues and codes can be interpreted for possible meanings. Whereas she emblazons Picasso’s name across the museum wall, she adds hers too, but it’s written in reverse, a hint hinting at her own obscurity, and the kind of detail that belies the work’s apparent frivolity.

The Painting Was Intended as a Secular Altarpiece

Gerard David, The Nativity with Donors and Saints Jerome and Leonard (circa 1510–15). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stettheimer’s “Cathedrals” series was meant to depict New York City’s so-called “places of worship”—arts, finance, and society. In creating these works, Stettheimer looked to religious art for compositional inspiration, particularly triptych altarpieces.

“The series is designed to resemble a multi-part altarpiece, not merely in terms of its scale and dimension (each work measures more than 50 inches wide and 60 inches high) but also in its ideal display,” wrote art historian H. Alexander Rich in the essay “Rediscovering Florine Stettheimer (Again).” In this reading, too, we can imagine Stettheimer’s depictions of herself and her friend Robert Locher as compère and commère (godfather and godmother), as the saints welcoming us into the scene, but themselves existing outside of it.

Detail of The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“The two figures [act] as patron saints or intercessors between the world of art and its audience. Cathedrals of Art, then, is not only a tribute to art but to New York’s art institutions and to the people who run them,” wrote Nochlin.

With these religious references in mind, the arching frame of the museum structure can be interpreted as a kind of mandorla, surrounding the sacred goings-on of the museum while “Baby Art” at the center is a stand-in for the Christ-child in a nativity scene, with the flash of cameras, a contemporary reprisal of divine light.

The Theater Profoundly Informed Her Approach to Painting

Florine Stettheimer’s set design and costumes in Four Saints in Three Acts, performance photograph by White Studio, New York (1934). Courtesy of the Florine and Ettie Stettheimer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven.

Critical discussions of Stettheimer’s work often rightfully note the influence of theatrical design, especially in her strong sense of staging and framing. She’d spent much of her youth in Europe with her sisters and mother, and a visit to Sergei Diaghilev’s pioneering Ballet Russes had a lasting impact on her painting. (Stettheimer also designed the set for Gertrude Stein’s 1933 opera Four Saints in Three Acts.)

Stettheimer was also a devoted poet, and her writing is often said to be influenced by the philosophies of French philosopher Henri Bergson. Bergson argued against fixed notions of time and memory in favor of ideas of simultaneity, motion, and change—influences apparent not only in Stettheimer’s poetry but in her painting as well.

Detail of The Cathedrals of Art. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“In duplicating figures within the scene and combining several days into one, Stettheimer drew on her understanding of Bergsonian time,” wrote the art historian David Tatham. “Bergson’s arguments distinguished between duration with its heterogeneous, overlapping events and linear, measurable time. In human experience, duration embraced the remembered past as well as the conscious present, and as a concept, it was alien to the frozen moment in pictorial art.”

In Cathedrals of Art we can see this employment of simultaneity through her whimsical conflation of spaces and events, but also in her depiction of “Baby Art,” which appears both at the foreground of the painting and in the background, being led by Met director Francis Henry Taylor.