Art World

How the Ford Foundation Is Using the Turbo-Charged Art Market to Propel Criminal Justice Reform

The organization has teamed up with arts patron Agnes Gund, who just made a $100 million grant with monies from the sale of a Roy Lichtenstein.

The organization has teamed up with arts patron Agnes Gund, who just made a $100 million grant with monies from the sale of a Roy Lichtenstein.

Brian Boucher

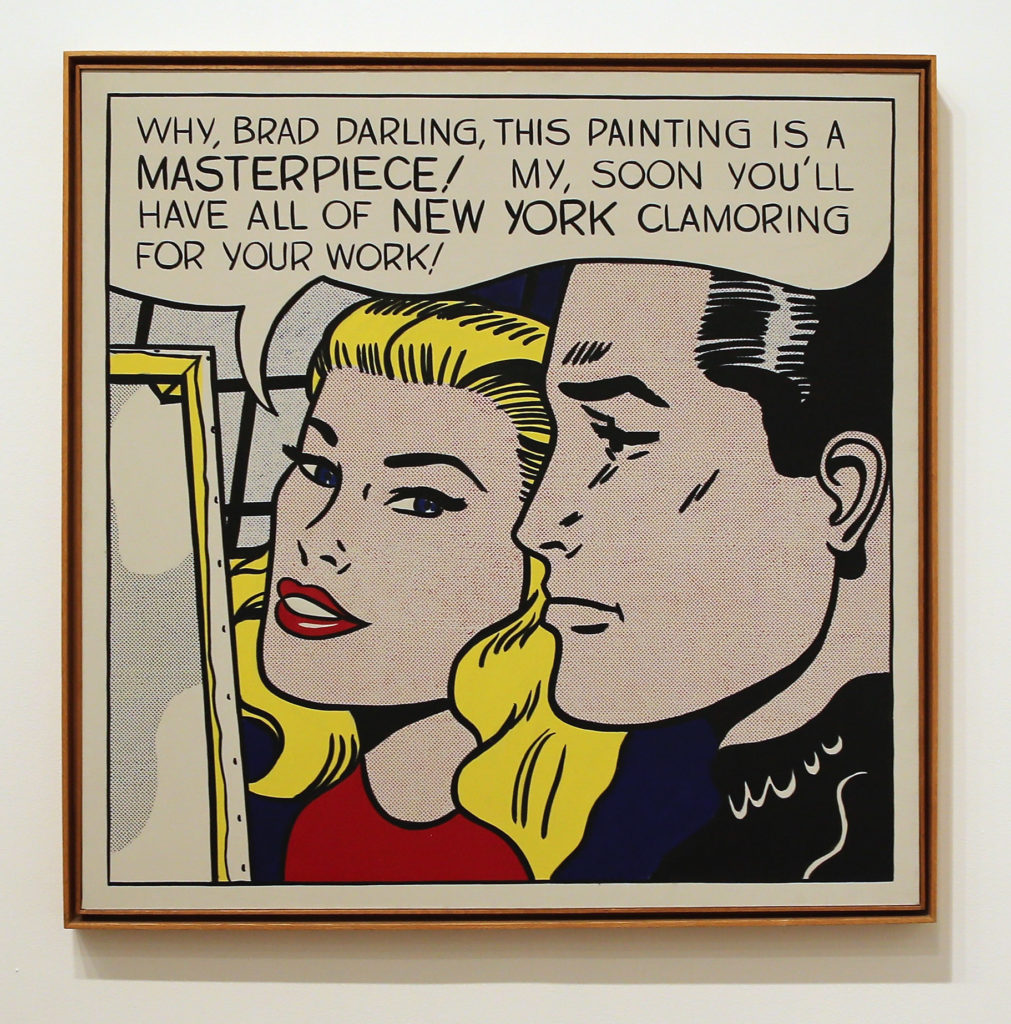

New York art patron Agnes Gund has sold a record-smashing $165 million Roy Lichtenstein painting to create a fund to help address mass incarceration in the United States. Some $100 million from that sale will establish the Art for Justice Fund, to be managed by the Ford Foundation, which aims to raise another $100 million over the next five years, partly from art sales. Gund has thus thrown down the gauntlet to other art collectors to unload their assets to address critical issues of social justice. The funds will go to organizations and individuals who are “doing impactful and cutting-edge work to reform the criminal justice system,” according to the Ford Foundation’s announcement. The first round of grantees will be named at the end of 2017.

The sale price for the Lichtenstein puts the painting among the top 15 artworks ever sold, according to the New York Times, which first reported the story. It smashes Lichtenstein’s auction record of $95.4 million, fetched by Nurse (1964), which was sold at Christie’s in November 2015 in its “The Artist’s Muse” auction. Gund’s Lichtenstein went to collector Steven A. Cohen via New York’s Acquavella Galleries, says the Times.

Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece, (1962) on view at the Tate Modern in 2013. Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

“The criminal justice system in its current state—particularly in its treatment of people of color—is unfair and unjust,” said Gund in the Ford Foundation’s announcement of the new initiative. “It is my hope that by supporting organizations working on criminal justice reform with proven track records, the Art for Justice Fund can inspire change and help pave the way for a better, safer future for our communities and the millions of people whose lives are devastated by mass incarceration.”

At a time when artworks represent some of the most expensive items ever sold at auction, the donation marks an effort to turn the blazing market for art to noble purposes. Among other committed donors are numerous art collectors, including Phil and Shelley Fox Aarons, Pamela Joyner and Alfred Giuffrida, and Brooke and Dan Neidich. Artists like Mark Bradford have also leapt into similar efforts. Bradford personally funds a program for kids in the Los Angeles foster care system, and as part of his inclusion in the current Venice Biennale, he is donating money to help female prison inmates in their transition back into society.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, while the United States represents just five percent of the world’s population, we accounted for as much as 25 percent of the world’s prison population. And currently, some 2.3 million people are incarcerated in the American criminal justice system, according to a recent report by Prison Policy Initiative. The ACLU also points out that the US spends more than $80 billion per year on incarceration, and that African Americans are locked up at a rate 10 times higher than that for whites. A raft of writers have recently tackled the phenomenon, including Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness and James Forman Jr. in Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. Ava DuVernay’s film 13th traces mass incarceration back to the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which allowed slavery as punishment for a crime.

The art patron Agnes Gund. Photo by Annie Leibovitz.

Gund, a major philanthropist, also founded the nonprofit Studio in a School. The organization brings art lessons to New York City public schools, and has instituted a push to diversify the staff at the Museum of Modern Art, where Gund has long served on the board.

Ford Foundation president Darren Walker spoke to artnet News about exploiting the art market for urgent needs and the importance of art to redress injustice.

Many people name education as the civil rights issue of our time, but I would think that mass incarceration is right up there. How are the two connected?

There is no doubt that we have in this country a schoolhouse-to-jailhouse pipeline. There is a correlation between the poor quality of the education that too many low-income black and brown children receive and the fact that most of the prison population is low-income black and brown Americans.

It’s brilliant to take advantage of the blazing art market to address urgent issues, especially since many people lament its meteoric rise and feel indignant about the world’s wealthiest people spending money on art that could fund charitable initiatives. Where did the push come from to use art to address mass incarceration? Was that Gund’s idea or the Foundation’s, or did it come from both sides?

Aggie and I have been friends for two decades, and during that time she’s always been interested in issues of inequality and poverty, particularly among children—that’s why she founded Studio in a School. In the last couple of years, as she’s read more and consulted with people like Michelle Alexander and Ava DuVernay, she realized this is one of the most pressing issues in our country. Remember that she has six African-American grandchildren, so she has a lived experience that most privileged, wealthy white people do not. She sees the lower expectations that people hold with respect to young black children. This issue, the fact that the criminal justice system is racially biased and produces bad outcomes for our country, is Aggie’s great passion.

This initiative comes at perhaps an opportune moment, when Attorney General Jeff Sessions has announced that the Justice Department will reverse some of Obama’s initiatives and urge prosecutors to press for maximum sentences for low-level drug offenses. Did the election of Donald Trump play any part in inspiring this initiative?

We have worked on this issue for a very long time, and every administration—both democrats and republicans—has contributed to this crisis, so it’s not about any one in particular. The reality is that most prisoners are in state penitentiaries and county jails, and presidents have little to do with criminal justice at those levels. The state systems are the adjudicators of justice, so we’re focused on supporting reform of state criminal justice systems.

How has Ford previously been involved with mass incarceration?

It’s not a new tack for us at all. We’ve been supporting work on reforming our criminal justice system since the 1990s, as it became more clear that the war on drugs had failed. For Aggie, it’s the confluence of her passion for criminal justice reform with the need to raise a significant amount to have an impact and the fact that the art market is so turbo-charged right now, especially for modern and contemporary art. So she made a shrewd decision to sell and achieve a record price for Lichtenstein.

Ford recently decided, as Larissa MacFarquhar wrote in the New Yorker, to devote itself to inequality. In addition to turning the funds from art sales to the support of such an urgent need as mass incarceration, how does the Foundation also work for equal access to the arts?

The arts are a vital part of our programs here, and we fund arts programs and education programs for incarcerated men and women. For example, we fund the Actors Gang, which is Tim Robbins’ theater group. We fund Bard College’s Prison Initiative, which has a program that includes the arts in some New York penitentiaries. Last year, in a program called the Art of Change, we chose about a dozen artists as Ford Foundation fellows, including people like Carrie Mae Weems and Teresita Fernandez. We do believe that if we had more arts in this country, we would be a more empathetic nation. We take very seriously art’s potential to demonstrate solutions and ways out of these social problems.