Reviews

With ‘Radical Love,’ the Ford Foundation’s Art Gallery Makes the Case for Loving as a Social-Justice Strategy

"Radical Love” looks at how artists explore empathy and self-care in transformative ways.

"Radical Love” looks at how artists explore empathy and self-care in transformative ways.

Nico Wheadon

In its inaugural year—one marked by a heightened culture of global fear—the Ford Foundation Gallery is surveying the theme “utopian imagination” through three daring exhibitions curated by Jaishri Abichandani and Natasha Becker. Whereas the first exhibition, “Perilous Bodies,” explored the seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieving justice on earth—such as xenophobia, racism, class, and gender inequality—its second, “Radical Love,” looks inwards for hope, bringing together art that spotlights the often-invisible labor of self-care, unconditional love, and collective empathy.

In their statements, curators Abichandani and Becker nod to activist and author bell hooks as a source of inspiration for the exhibition’s conceptual framework, which looks at love as a human right and shared responsibility. Here, love is presented as far more than a feeling, and is explored by the exhibition’s 23 artists as practice, gesture, mode of resistance, tool of survival, reflection of self, and acceptance of other. hooks’s claim that “[a]s a nation, we need to gather our collective courage and face that our society’s lovelessness is a wound” is foregrounded brilliantly in works such as Bradley McCallum and Jacqueline Tarry’s expansive portrait installation, Evidence of Things Not Seen (2008).

Spanning an entire gallery wall at the exhibition’s entrance, the work is comprised of over a hundred portraits of Civil Rights protesters arrested during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. McCallum and Tarry celebrate the courage of the individual in the collective struggle for freedom from systemic oppression, yet subvert history’s tendency to idolize only the select few. Here, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. are situated off-center, among the broader mosaic of mugshots-turned-portraits, which also depict the 102 other protesters arrested that year.

Bradley McCallum and Jacqueline Tarry, Evidence of Things Not Seen (2008). Image courtesy of the artists.

As evidenced in this work’s panoramic focus on the people behind the progress, “Radical Love” as a whole places concrete emphasis on human agency, exposing moments large and small where someone forged conditions for love to manifest.

Jah Grey, Dancing in the Light (2018). Image courtesy of the artist.

Jah Grey’s video Dancing in the Light (2018) explores Black, male intimacy through a series of moving images, stripped of society’s dangerous projections of hyper-sexuality and hyper-masculinity. Within a tight filmic frame, three shirtless men dance in response to each other’s bodies, without fear or shame. Joy and play abound in this spirited work, for which the artist simply prompted the men to “feel their individual feelings around each other.” Here, love is captured as simple gestures, both offered and received.

Nearby, another striking video captures viewers’ attention, first through its meditative soundscape, and later through seductive imagery that transports viewers deep into the underwater world of Sue Austin. In Creating the Spectacle! – Part 1 – Finding Freedom (2012), Austin casts herself as protagonist, and, as curator Abichandani asserts, “there is no mistaking that it is an act of ‘radical love’ to cast oneself as the subject of art in a world that deems your very existence unworthy.”

Sue Austin, Creating the Spectacle Part 1: Finding Freedom (2012). Image courtesy of the artist.

In this ethereal underwater scene, Austin swims past schools of fish and between coral reefs, in a subaquatic wheelchair. Through a feat of equal parts imagination, engineering, and courage, Austin—an advocate in the Disability-Arts Movement and artist concerned with “opening up a thinking space to consider one’s own preconceptions about disability”—offers a glimpse of a personal utopia, and positions self-portraiture as a tool of self-care.

La Vaughn Belle and Jeannette Ehlers, I Am Queen Mary (A Hybrid of Bodies, Nations, and Narratives) (2019). Image courtesy of the Ford Foundation Gallery.

La Vaughn Belle and Jeannette Ehlers also resist narrow readings of subjecthood in their sculpture, I Am Queen Mary (A Hybrid of Bodies, Nations, and Narratives) (2019). Their memorial to Mary Thomas (ca. 1848–1905), one of three women leaders in the 1878 St. Croix labor revolt known as the Fireburn, is a 3D composite of the artists’ own facial and bodily features. The work—which boasts a slick, black patina and rests atop a plinth comprised of white coral stone—is monumental and demands to be revered. Their “Mary” returns the viewer’s gaze, poised for action with a blade in one hand and a torch in the other.

Rashaad Newsome, Look Back At It (2016). Image courtesy of the artist and David DeBuck Gallery

Belle and Ehlers elevate Woman to idol, worthy of praise, adoration and remembrance. Elsewhere, in their works in “Radical Love,” artists Rashaad Newsome, Raúl de Nieves, and Nep Sidhu all explore motherhood as a form of radical love that has both informed and nurtured their artistic practices.

Installation View of “Radical Love” at the Ford Foundation Gallery, with Raúl de Nieves, Fina Beauty (2019) and Fina Nuture (2019) at center. Photo: Sebastian Bach.

Newsome’s collages are inspired by his relationship with his own mother, and explore the many layers of beauty, outside of those commonly revered and circulated by art history and the popular media. De Nieves’s two kneeling floor sculptures come from a series of highly adorned figures which pay homage to the multifaceted strength of his mother, who took on plural roles following the death of his father.

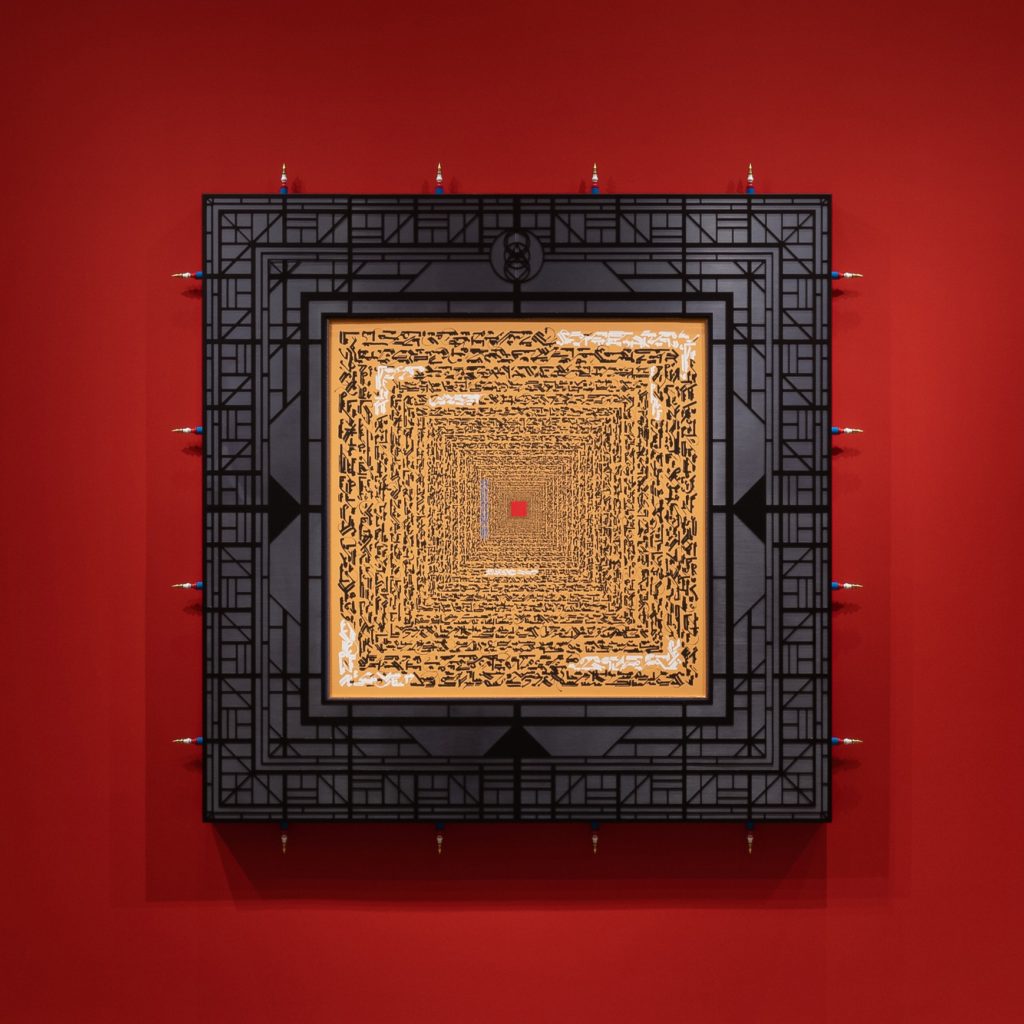

Installation View of Nep Sidhu, Confirmation B (2014) in “Radical Love” at the Ford Foundation Gallery. Photo: Sebastian Bach.

In Confirmation B (2014), Sidhu uses his art practice as a vessel of spiritual communion with his mother following her death, transforming her final words to him into an experimentation with Kufic script. The resulting graphic work produces a palpable emotional space that draws the viewer in.

“In our relationship to artists, we learn so much about ourselves as curators, understanding that, like art, the curatorial is engaged in knowledge production and an intervention in culture,” co-curator Becker explains, giving a sense of the highly collaborative nature of this exhibition. There’s a unified aesthetic to “Radical Love” achieved through a curatorial approach that privileges visual abundance over scarcity, representational nimbleness over rigidity, and color over whiteness. This subversion of roles and norms, at all levels of the exhibition, invites rich dialogue both between and around the artworks.

Installation View of “Radical Love” at the Ford Foundation Gallery. Photo: Sebastian Bach.

While it is easy to surrender to the enlightenment that each individual artwork produces, the true strength of the exhibition lies in its cumulative effect, one accentuated by the larger context in which the show is so brilliantly nested: the Ford Foundation, with its decades-long commitment to celebrating cultural difference and fighting for social injustice. The newly established Ford Foundation Gallery, in its own words, aims to “shine a light on artwork that wrestles with difficult questions, calls out injustice, and points the way toward a fair and just future.” As a showcase for that mission, “Radical Love” celebrates individual transformation, while reminding us of the systemic impact made possible only by collective work.

“Radical Love” is on view at the Ford Foundation Gallery, New York, through August 17, 2019.