People

A Look Back Through Pictures at the Once-Forgotten Young Women of the Bauhaus

While the school was highly progressive for its time, its female students were at a disadvantage.

While the school was highly progressive for its time, its female students were at a disadvantage.

Kate Brown

Anonymous was a woman—or so the saying goes. But in the case of an anonymously authored article on the Bauhaus titled “Girls Want to Learn Something,” it’s likely a fact. Written in 1929, the three-page spread in a German weekly illustrated the hopes of the young women of the famed German school as they sought new paths in creative and professional life. “The Bauhaus gal knows what she wants and will make it anywhere,” the article’s author wrote.

Who were they? We still know relatively little about the more than 400 female students who staked out their places at Bauhaus’s campuses in Dessau and Weimar, before the schools were closed at the onset of the Second World War. But a new book published by Taschen, Bauhausmädels: A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists (it’s due out in April), commemorates 87 of them by offering intimate insights into their lives.

Arranged almost like a family photo album, the book captures the spirit of the school’s underrated members, who should be described as something other than just “mädels,” which translates to gal or girl. Though it’s a term pejorative by today’s standards, it remains in the book’s title to reflect the attitudes these women struggled against in their time.

Bauhausmädels traces their biographies and careers, their re-locations around the world, and even their eventual places of death. And while several Bauhaus women—such as Anni Albers, Marianne Brandt, and Ise Gropius, wife of the school’s founder, Walter—achieved certain notoriety, many textile designers, photographers, typographers, and painters highlighted here did not.

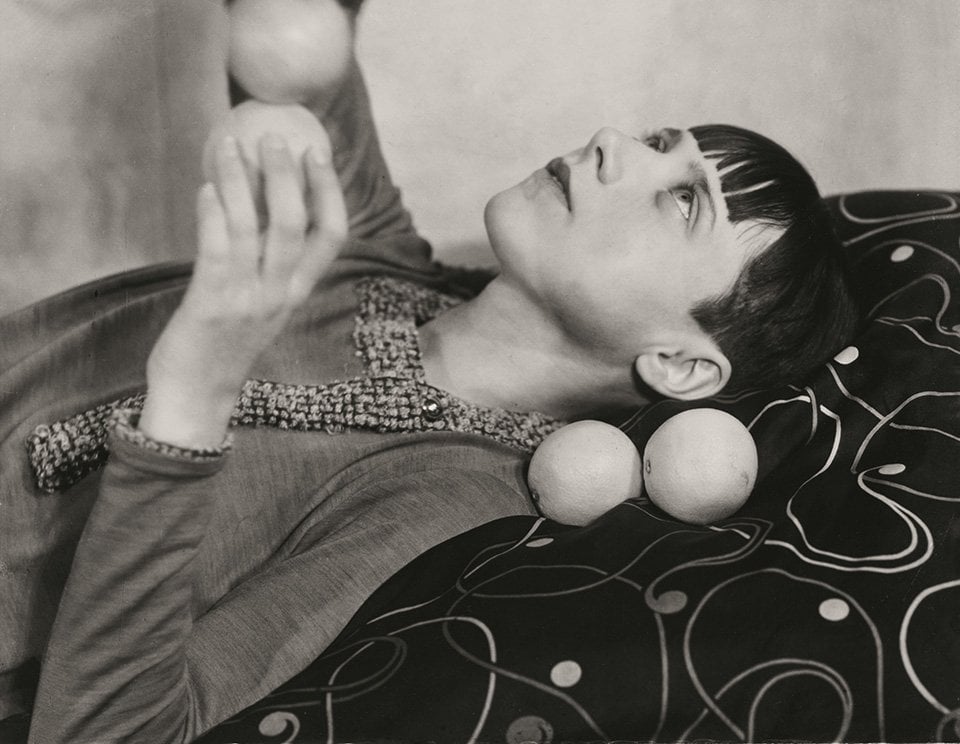

Walter Peterhans, Margaret Leiteritz with oranges (before 1930).© Museum Folkwang Essen/ Photo © ARTOTHEK.

While Germany and the world ring in the centenary of the celebrated design school and its progressive ethos, it’s worth remembering that even the Bauhaus was not immune to gender inequality. Although women were an integral part of the school’s socially liberal philosophy, many of them remained disadvantaged.

There is, for example, Lucia Moholy, who fought a legal battle against Gropius and her ex-husband, Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy, after they repeatedly used her photographs and took credit for the work she left behind after fleeing the Nazi regime. In 1938, Gropius included 50 of her images in a show at the Museum of Modern Art without crediting her a single time.

Although the school welcomed talent regardless of sex or age, faculty also conspired to keep female students away from certain departments. According to art historian Anja Baumhoff, there was a “hidden agenda” on the part of Gropius and the school’s faculty to reduce the number of female students overall, and to prevent them from taking up practices in the school’s more prestigious workshops—namely, architecture and carpentry. Many of the female faculty worked in the textile department, and with other lighter-weight art forms.

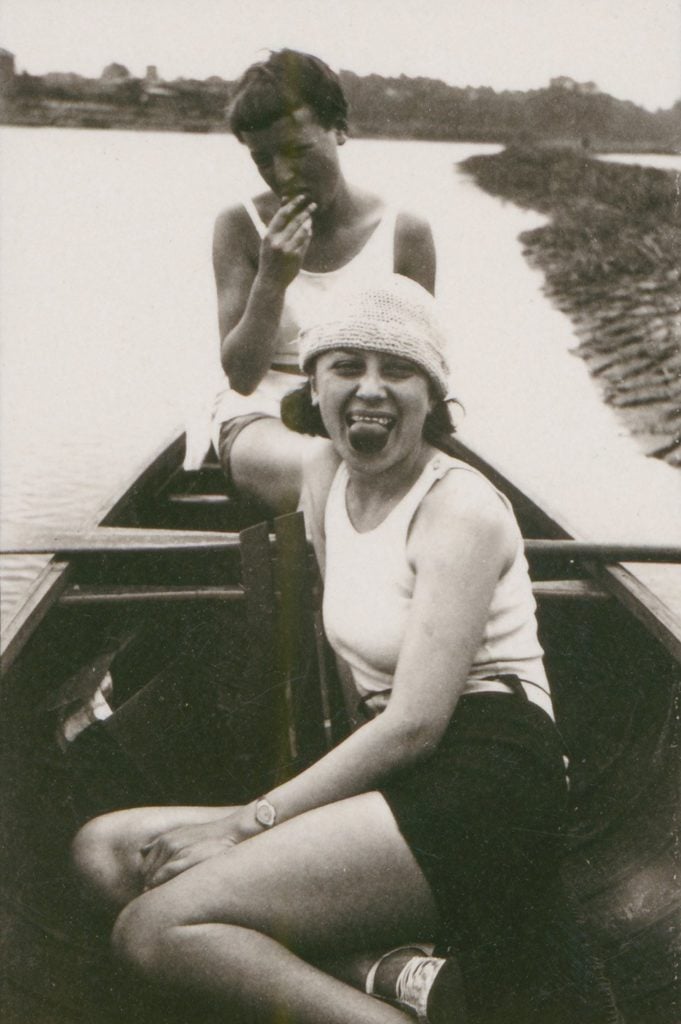

Anonymous, Otti Berger (front) and Lis Beyer in a rowing boat on the Elbe (circa 1927). Photo © Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin.

The book includes tender portraits of the students at work or at play. Among them is Otti Berger, who had a leading role at the school’s weaving workshop and later ran a textile company. In the book, she comes across as carefree in a photograph of her laughing in a boat with another student. But her future was cut short. After successfully emigrating to London, she returned to Yugoslavia to help her sick mother. Tragically, Berger, who was of Jewish origin, was arrested there and murdered in Auschwitz by the Nazis.

But when the “Girls Want to Learn Something” story was first published in 1929, the mood was still optimistic. There is a distance, the anonymous author writes, “between the woman of today and the woman of yesterday, between the girl of then and the girl of now.” And in that distance, a new woman seemed bound to emerge. In pictures published in the book, we see bright, young women beaming at cameras, carrying all the ambitions of an unprecedented and free-spirited generation that seemed open to radically new possibilities.

See more images from the book below.

Erich Consemüller, On the roof of the Atelierhaus, Dessau (Martha Erps with Ruth Hollós, left) (circa 1927). © Stefan Consemüller, Klassik Stiftung Weimar/Bauhaus-Museum.

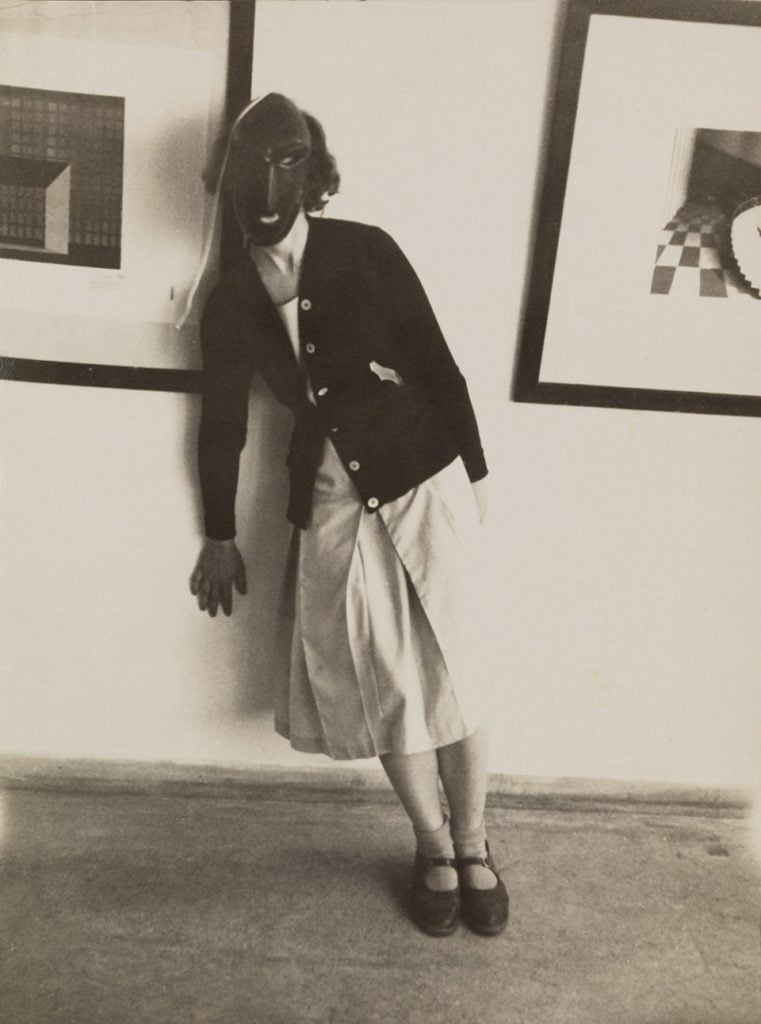

Anonymous, Bauhaus student in a mask from the Triadic Ballet (circa 1927). Photo © Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

T. Lux Feininger, The weavers on the Bauhaus stairs in Dessau (circa 1927). © Estate of T. Lux Feininger / Photo© Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin.

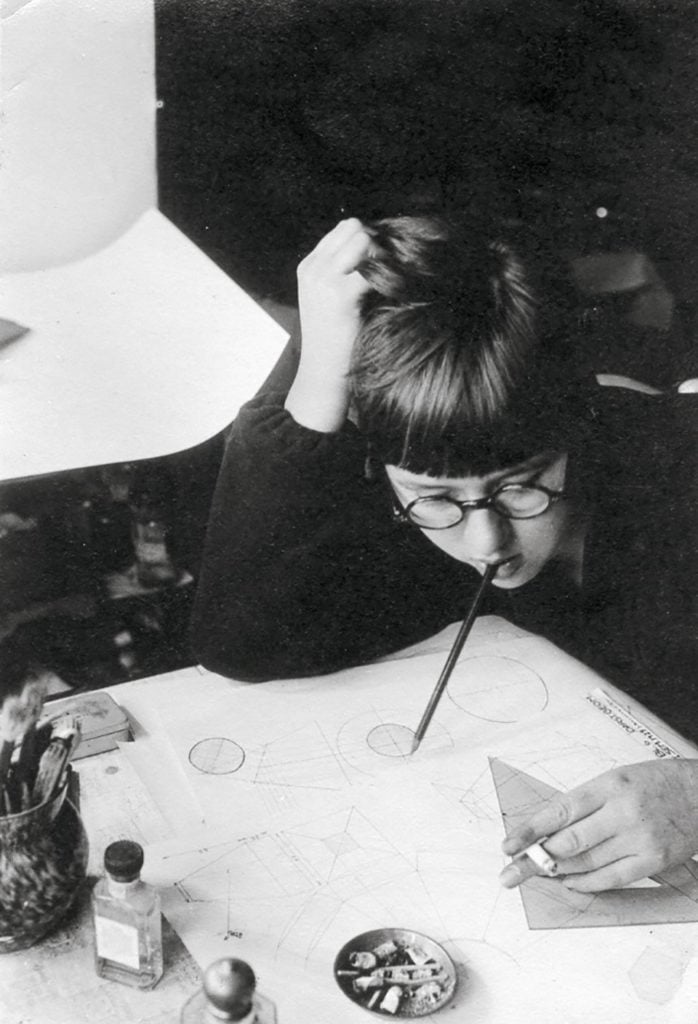

Anonymous, Elsa Franke designing (undated). Photo © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

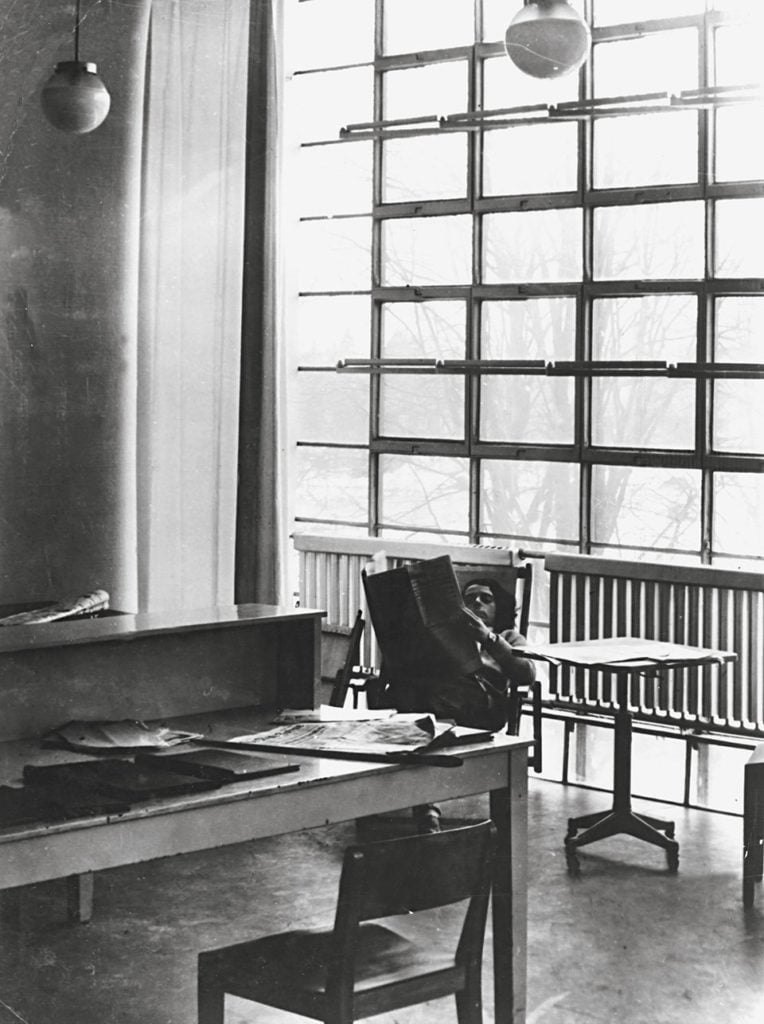

Judit Kárász, Irene Blüh in the reading room (student clubroom) at the Dessau Bauhaus (circa 1932). © Géza Pártay / © Zuzana Blüh, Prague.

Anonymous, Gunta Stölzl in the studio at the Dessau Bauhaus (March 13, 1927). Photo © Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin.

Herbert Bayer, Portrait of Ise Gropius from the “Red Album” (Estate of Walter Gropius) (circa 1931). © Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin 2019.