Art & Exhibitions

Germany Is Planning a Blowout 100th Birthday Celebration for the Bauhaus. Here Are the Events Not to Miss

Dozens of exhibitions, projects, and initiatives across Germany aim to rewrite the history of the era-defining movement.

Dozens of exhibitions, projects, and initiatives across Germany aim to rewrite the history of the era-defining movement.

Hili Perlson

In 1919, architect Walter Gropius opened a small school in Weimar, Germany that soon became a breeding ground for a new aesthetic movement. Whether you’re aware of it or not, the Bauhaus—the first school of modern architecture and design—informs the look and feel of much in your life today, from your subway station to your pencil holder.

This year, Germany is marking 100 years since the founding of the Bauhaus with a country-wide centenary celebration that promises to be “in true Bauhaus fashion: experimental, multifarious, transnational and radically contemporary,” according to the umbrella organization Bauhaus 100.

In fact, the host of special programs planned throughout the year has landed Germany second on Lonely Planet’s ranking of best countries to visit in 2019 (after Sri Lanka, where improved train lines nearly a decade after the end of civil war allow easier access to breathtaking landscapes and beaches). But the short-lived yet influential movement is worth revisiting for more than just its centennial milestone. Its history and global spread reflect 20th-century narratives of immigration, exile, and political instability, which are as relevant today as they were during its founding.

Bauhaus-Archive, Museum für Gestaltung Berlin

(1976–79), Walter Gropius, Alex Cvijanovic, Hans Bandel. Photo: ©Tillmann Franzen © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018.

Bauhaus was synonymous with modernity and spread across the globe through the work of architects and designers as well as artists including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef and Anni Albers. Bauhaus students studied new ways to work with materials and specialized in incorporating artistic concepts into a range of industrial media, crafts, and manufacturing. They believed in the synthesis of the arts and regarded the school as an experimental laboratory for the building of the future. Here, the Bauhaus credo was cemented: rather than a specific style, it represents an approach.

As a result of financial and political pressures, the Bauhaus relocated twice. First, it moved to the up-and-coming industrial city of Dessau, where Hannes Meyer led the newly-opened architecture department and Walter Gropius realized his now world-famous university building. It relocated again, to Berlin, in 1933, under its third director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. After only one semester, however, the school was forced to close under political pressure from the Nazis, who saw it as a center of communist intellectualism. As a result, many of its teachers and students fled Germany.

In addition to the dozens of shows, performances, and events planned to mark the centenary, all three Bauhaus cities are revamping their museums to mark the anniversary, with Weimar and Dessau celebrating new openings this year, followed by Berlin in 2022. Other rich programming across the country will explore not only the multifarious histories of the Bauhaus, but also the way the movement has informed how we live today, leaving its mark on everything from architecture to typography.

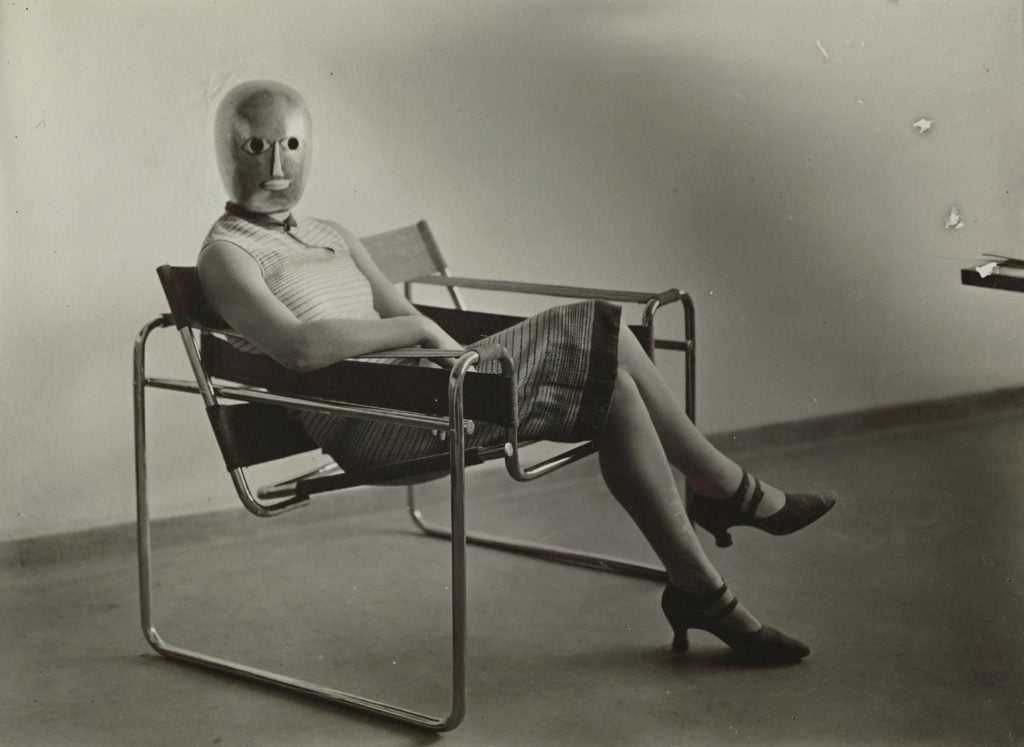

Woman on club chair B3 from Marcel Breuer, mask from Oskar Schlemmer, dress from Lis Beyer. Foto: Erich Consemüller, about 1927/ © Klassik Stiftung Weimar/ © Stephan Consemüller.

Finally, a slew of offerings explore a major aspect of Bauhaus that is often left unmentioned, namely its ideas regarding set design, theater, dance, and the performing arts as a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. Oskar Schlemmer’s groundbreaking Triadic Ballet—which conceived of the human body as artifice, assigning a geometric form to each body part—is exemplary of the Bauhaus stage’s dramatic representations of the mechanization and pace of modern life.

These events, gathered under the umbrella of Bauhaus 100, are the result of extensive scholarly research and institutional collaboration. To help you navigate, we’ve selected five highlights that capture the diversity of the program—and, of course, the movement itself.

Wilfried Hoesl, “Triadisches Ballet, Bayer Junior Ballet.”

Taking its cue from the Bauhauswoche (Bauhaus Week), an exhibition of works by students that was staged in 1923 in Weimar, and the legendary, themed Bauhaus parties held at the different schools, the opening festival at Berlin’s Art Academy will kick-start the centennial with a focus on experimentation in the stage arts. The nine-day festival features 25 productions, ranging from a restaging of Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, to the VR installation Das Totale Tanz Theater, a collaboration between the Interactive Media Foundation and the internationally acclaimed choreographer Richard Siegal and Artificial Rome that examines a dance between man and machine.

On opening night, composer Michael Wollny will present “Bau.Haus.Klang.” dedicated to the musical experiments of the Bauhaus. And since nothing happens in Berlin without good parties, the program also includes club nights with musicians and DJs such as Mykki Blanco, Aisha Devi feat. The Asian Dope Boys, and DJ Haram, to name a few.

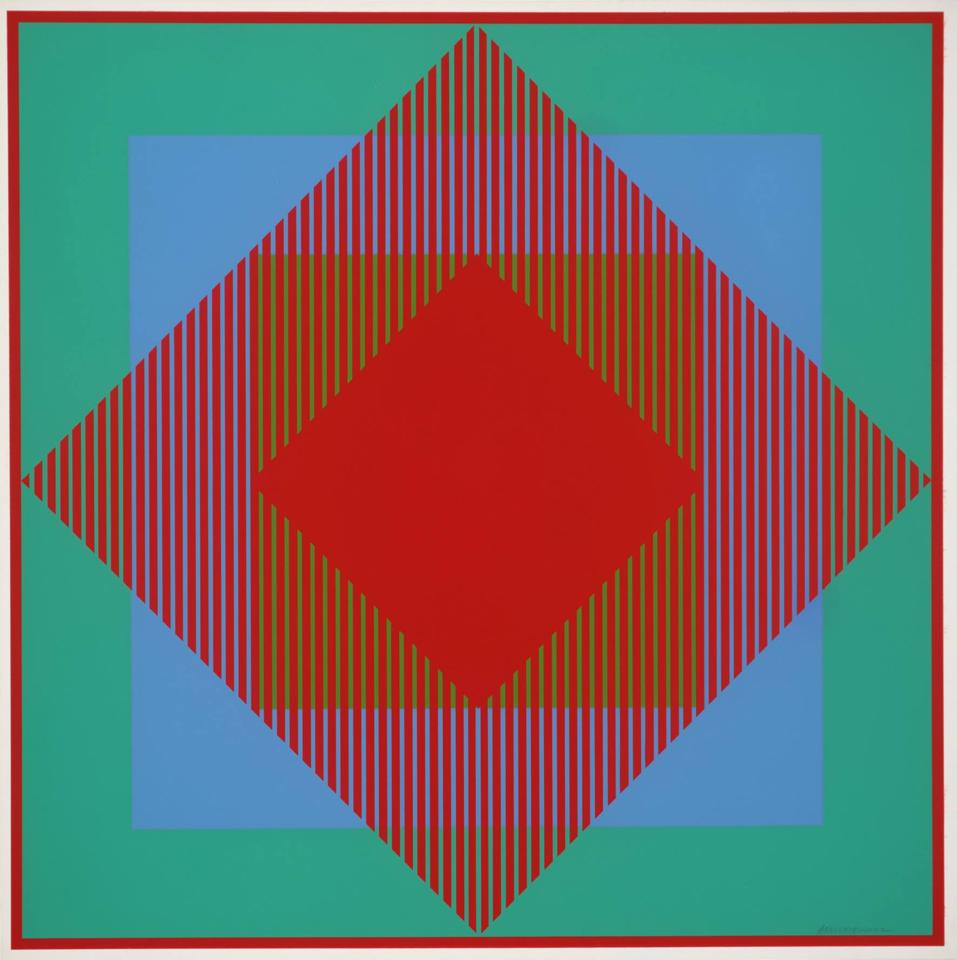

Richard Anuszkiewicz, Ohne Titel (1965). Tate London, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Photo: Tate, London.

Focusing on artists who emigrated to America after 1933 as a starting point, this multidisciplinary exhibition includes loans from such august institutions as the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Tate in London. The show demonstrates how, as early as the 1950s, the Bauhaus ideas that traveled stateside went on to inform practitioners in Europe. Robert Rauschenberg’s years at Black Mountain College studying under Josef Albers, for example, were formative for his stage collaborations with Merce Cunningham, who, in turn, influenced modern dance internationally.

Marcel Dzama, Merry go round #2 (2011). Sammlung Monika Scnetkamp, Dusseldorf. ©Marcel Dzama, 2018. Photo: Hendrik Reinert.

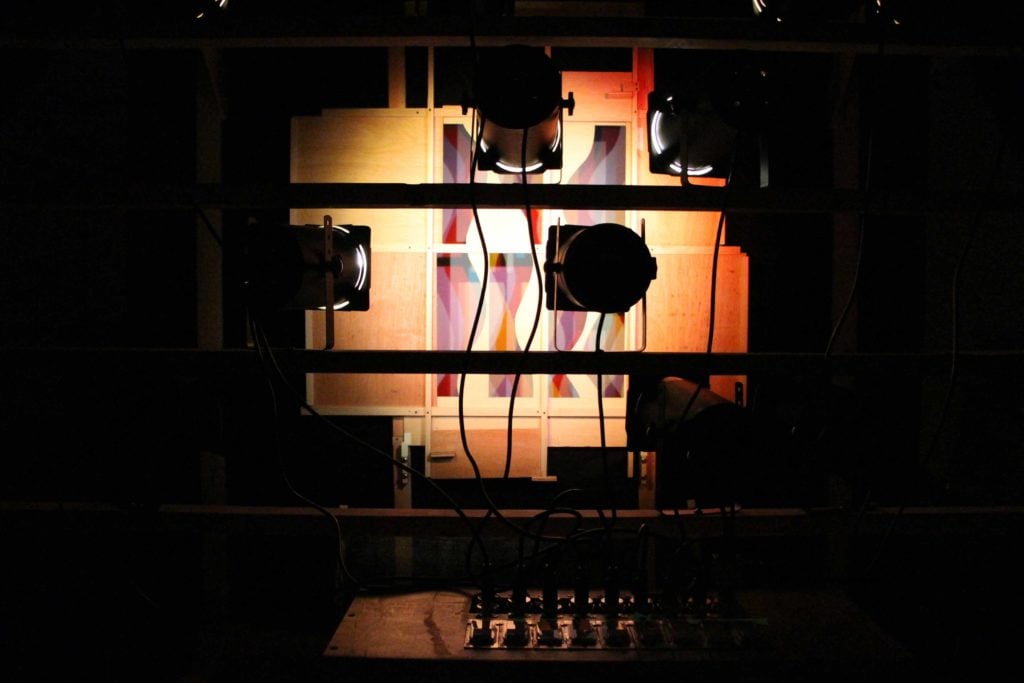

Rather than a purely historical perspective, the exhibition traces how ideas surrounding light, movement, and the stage are also reflected in the work of contemporary artists such as James Turrell, Marcel Dzama, Barbara Kasten, and Daria Martin. A definite highlight of the exhibition, and perhaps the centenary fêtes, is the display of Moholy-Nagy’s seminal Licht-Raum-Modulator device and Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s Farbenlichtspiele apparatus, which, for the first time in many years, can be seen together in Germany again. Both are regarded as early forms of modern multimedia devices, joining projected light, sound, and moving forms, developed either to accompany stage productions or as an entertainment unit for the home.

Hufeisensiedlung (1925–30), architects: Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner. Photo: © Tillmann Franzen.

The Grand Tour is an interactive website that maps out outstanding landmarks of Bauhaus and Modernist architecture all across Germany, as selected by a jury of experts. In addition to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Bauhaus, the tour includes buildings that guide visitors through the past 100 years of the history of modern architecture. The Völklingen Ironworks in Saarland, for example, is the only fully preserved blast-furnace complex from the golden age of industrialization. (In 1994, became Germany’s first modernist UNESCO World Heritage site.)

UNESCO WorldHeritage Fagus Factory (1911), Walter Gropius. Photo: © Tillmann Franzen, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018.

To be explored individually or with guided tours, there are dozens of locations to discover on the map, from the Le Corbusier House on the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, to Walter Gropius’s innovative Fagus Factory (1911) in Lower Saxony.

Not only for die-hard architecture fans, the sites offer insights on the way we live, build, and develop cities today: take, for example, the modern kitchen, which originated from Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s 1926 Frankfurt kitchen, designed as a space-saving, hygienic, and efficient room for the housing estates of the “New Frankfurt” public housing program. Happy wandering.

Light performance at Microscope Gallery, 2016. Photo: Courtesy of Microscope Gallery and Kurt Schwerdtfeger Estate.

The international research project bauhaus imaginista, launched in March 2018, explores the global history of the Bauhaus, tracing contacts and exchanges that the German movement has had with institutions in other countries, where non-European strands of Modernism sparked independent movements with similar aims. The project has been developed by the Bauhaus Cooperation, the Goethe-Institut, and Haus der Kulturen der Welt together with the curators Marion von Osten and Grant Watson. A testament to the far-reaching influence of Bauhaus principles, the organizers have initiated collaborations with partners in China, Japan, Russia, and Brazil, among other countries.

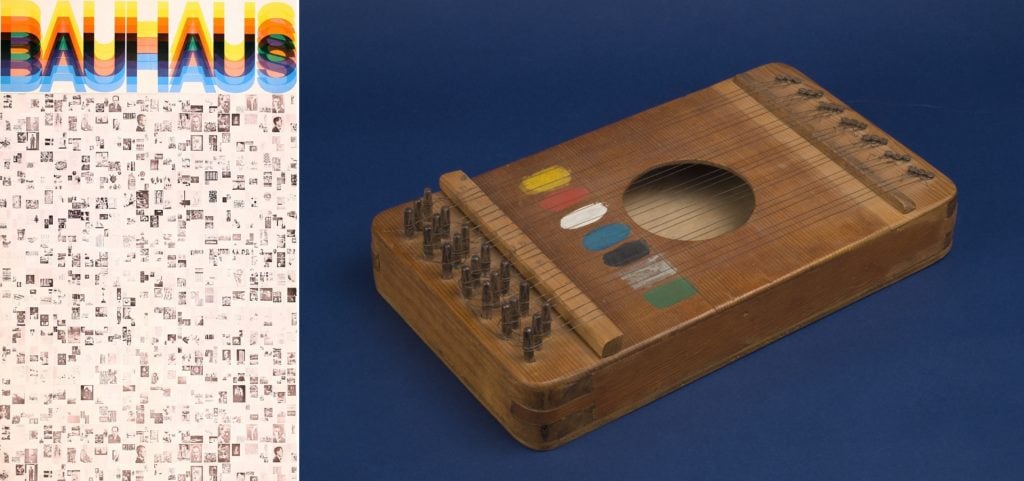

Left: Promotional poster for “Bauhaus: Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Chicago” courtesy Archive Mass. College of Art and Design. R: Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, Color chord 21-string flat sound box. Courtesy Grainger Museum Collection, University of Melbourne.

The collaboration shines a light on numerous unexpected ties. A symposium held in Lagos, Nigeria, in November 2018 as part of the project, for example, explored how Bauhaus alighted in West Africa by way of Israeli architect Arieh Sharon, a Bauhaus graduate, who was appointed head of the State Planning Authority after Israeli Independence. As part of Israel’s development aid programs in Sub-Saharan Africa, Sharon and his team designed the University of Ife campus, the first post-independence university in Nigeria to possess an architecture faculty.

In March 2019, the Berlin chapter of the exhibition, titled bauhaus imaginista: Still Undead, will open at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. This chapter explores how the spirit of Bauhaus, interpreted as transgressive and iconoclastic by future generations, would be adopted by youth and subcultures to create new genres of music, experimental film, and visual communication.

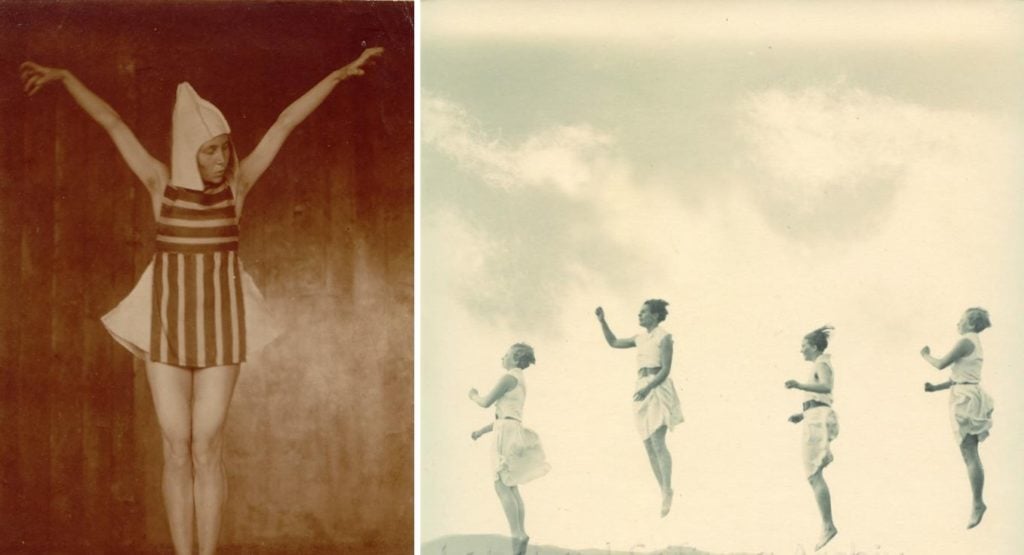

© Loheland-Stiftung Archive.

Also marking 100 years since its inception, the Utopian education project of Loheland shared many pedagogical ideas with Bauhaus, such as the holistic approach to the body, art, craft, and nature. But there is one major difference: Loheland was aimed at women only.

Founded in 1919 on 54 acres of forest and arable land, the school was way ahead of its time in offering women professional qualifications while also espousing Bauhaus tenets of movement training, arts and crafts, and performance. The specific artistic style that the women developed in their gymnastic-aesthetic education is mirrored in the iconic pictures of the Loheland photography studio “Lichtbildwerkstatt Loheland” and in the urban development of the self-managed settlement, which can all be visited on this occasion.

Together with the Vonderau Museum Fulda, the foundation organized an exhibition of objects and documents from the period 1919 to 1934, some shown publicly for the first time, divided into revelatory themes such as “architectural positions and place of bio-dynamic farming” or “fine arts as an initial starting point for creative life and work.” Many of these ideas continue to sprout up in culture—though admittedly, today’s farm-to-table fad and guides to design office spaces that “foster creativity” seem a lot less revolutionary than a women-only utopian farm.