Galleries

Conservator Found Rothko Painting in Knoedler Trial to Be a ‘Deliberate Fake’

James Martin said there were many anomalies in the paintings he examined.

James Martin said there were many anomalies in the paintings he examined.

Cait Munro &

Sarah Cascone

“I think she may have brought it over in her car,” said former Knoedler & Company librarian and archivist Edye Weissler, in her testimony Thursday morning at the fraud trial of the gallery at US District Court in Lower Manhattan. Weissler, who was on direct examination by Emily Reisbaum, an attorney for the plaintiffs in the case—Eleanore and Domenico De Sole—was referring to a painting, later revealed to be a fake, that was brought to the gallery by Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales and that the gallery would go on to sell for $8.3 million.

The plaintiffs, who bought the fake Rothko in 2004, are suing the gallery and its former director, Ann Freedman, for $25 million, claiming they knew the paintings were phony. Rosales pleaded guilty to fraud in 2013 and is awaiting sentencing. Several other suits against Freedman and the gallery have been settled out of court.

Weissler seemed aware that tossing a multi-million dollar painting in your vehicle isn’t exactly the customary white-glove treatment.

“She came to parties, events, to see Ann, and of course, to bring over the paintings,” Weissler recalled of Rosales, whose mysterious source for Abstract Expressionist works was referred to around the gallery as Mr. X and occasionally Secret Santa.

In addition to her duties as librarian, Weissler, who was employed by Knoedler between 1998 and 2012, conducted research, at Freedman’s request, into a possible connection between Mr. X, who was said to be a Swiss collector with a home in Mexico, and deceased dealer and collector David Herbert. Despite five days of research at the Washington, DC, and New York offices of the Archives of American Art as well as at Yale’s Beinecke Library, Weissler says she was never able to establish such a connection.

So when she began to see Herbert’s name popping up as an “intermediary” on fact sheets provided to potential clients about the paintings—and later on a description at the Beyeler Foundation, where a painting was on loan—she grew concerned.

“I’m a little worried about the Newman,” she wrote in a 2008 email to scholar David Anfam that was shown in court, referring to a painting by Barnett Newman that Anfam was considering borrowing for an exhibition. “I don’t want you to get into hot water (and we haven’t enough to do on with the Herbert). Am deleting this,” she wrote.

“It looked like the Herbert connection was being disseminated as a fact, when up until then I thought we were just investigating,” Weissler told the jury.

Also unable to establish a connection between Herbert and the Rosales works was provenance researcher Victoria Sears Goldman, who took the stand prior to Weissler as an expert witness called by the attorneys for the plaintiffs. Sears Goldman researched the possible connection at both the Archives of American Art and Harvard University in 2013, and said there was “no tangible link.”

“Provenance research is like detective work,” explained Sears Goldman to Reisbaum on direct examination. “You need to include a question mark or indicate in some way that there is a qualifier if you do include someone in the provenance and it isn’t fully established.”

Former Knoedler Gallery president and director Ann Freedman has always maintained her innocence.

Photo: Patrick McMullen

In the afternoon, art conservator James Martin, who examined the works in question for Knoedler and later for the FBI, took the stand.

Knoedler hired Martin, of Williamstown, Massachusetts firm Orion Analytical, in 2008 to make, in his words, “an objective examination” of two purported Robert Motherwell works, allegedly from 1953 and 1955. After running several tests on the works using tools including black light, stereoscope, and FTIR technology, he came to the conclusion that, based on the presence of acrylic polymer emulsions not used by Motherwell until 1962, the works could not have been created on the dates given to them.

“As you know, some information is inconsistent with the understanding that the paintings were made and purchased in 1953 and 1955,” Martin wrote in a 2008 report to Knoedler that Martin read out.

Several months later, Martin received a fax from E.A. Carmean, an art historian who was working on contract with the gallery, with several revisions he wanted Martin to make so that Knoedler could take the report to a meeting with the Dedalus Foundation, which is dedicated to the study and guardianship of Motherwell’s art. In Carmean’s fax, several paragraphs had slashes through them, including Martin’s conclusion, which rejected the notion that the works were created in the 1950s.

Carmean also requested that Martin add to the report: “At this point in the analysis and research, no conclusions can be drawn.” Martin refused.

“I believe he was asking me to alter my findings,” he told the jury in response to questioning by Isaac Zauer, the plaintiffs’ attorney. “Dr. Carmean asked me to delete my most relevant conclusions. I agreed to conduct an objective investigation, which is not what Knoedler wanted.”

In 2011, the De Soles hired Martin to analyze the supposed Rothko painting. He found that the artist who painted it had employed water-based polyvinyl acetate as a base, which he described as “what you would find if you went to Home Depot for primer.” According to Martin, it is not a material that Rothko used. Nor did he paint on white backgrounds at that time, as with this painting.

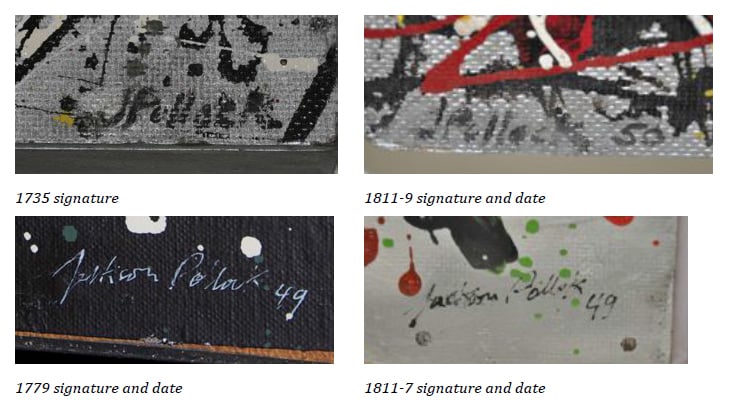

James Martin’s expert report shows the signatures from four Knoedler paintings that were purported Jackson Pollocks. The top two signatures are quite similar. The bottom left signature shows signs that the name was first traced onto the canvas using a sharp tool, and is very similar to the signature on the bottom right, which is misspelled “Pollok.”

Photo: James Martin.

“I concluded that it was a deliberate fake with a common source to the others I examined,” Martin testified.

Martin analyzed sixteen Rosales paintings in total, and found that fourteen used historically inaccurate materials, six had suspicious signatures, five showed signs of deliberate aging, and nine had been created on top of old paintings.

Taken together, he said, the anomalies and inaccuracies in the works are akin to “Jeter in a Red Sox uniform, or JFK holding an iPhone.”