The Founders Museum, a local collection of antiquities established by the residents of the town of Barre, in central Massachusetts, in 1885—and left largely unchanged since then—has returned a cache of 150 Native American objects to their rightful owners, the Lakota and Sioux tribes.

Tribal members were at the repatriation ceremony held at the museum this weekend, to receive the clothing, pipes, and weapons. Some of the items were connected to the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, when more than 250 Lakota men, women and children were killed by U.S. Calvary troops in South Dakota.

“I have been working on repatriating these artifacts for almost 30 years to the Lakota tribe,” Ann Meilus, president of the Founders Museum, told Artnet News. “It has been a very difficult process due to third party interference and changing the minds of the membership.”

The Founders Museum, operated by the Barre Museum Association and the Barre Library Association, was created from local private collections and “In some ways, it can be compared to a time capsule,” according to a museum statement. “The exhibits were set up and arranged in the late 1800s, in a manner that was considered pleasant and informative. Though cluttered and confusing by today’s standards, these exhibits made complete sense to the visitor of the 1890s and later.”

As Meilus understands, the Native American materials arrived at the museum through Frank Root, who the Associated Press described as “a traveling shoe salesman who collected the items on his journeys during the 19th century, and once had a road show that rivaled P.T. Barnum’s extravaganzas.”

Meilus renewed her efforts to repatriate the materials starting this January, based on the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which does not technically apply to the private museum. In August of this year, the museum released an update on the process. “In the past 135 years, the public’s use and perception of museums have changed significantly,” the statement reads. “Museum practices are very different than they were a century ago.”

Mia Feroleto, editor and publisher of New Horizons magazine made visits to Founders Museum as a representative of Oglala Sioux tribe. Fereleto then arranged a visit for several residents from the Pine Ridge and Cheyenne River reservations in South Dakota. They met with the museum’s staff and supporters on April 6, alongside John “Jim” Peters, Jr, executive director of the Massachusetts Commission of Indian Affairs.

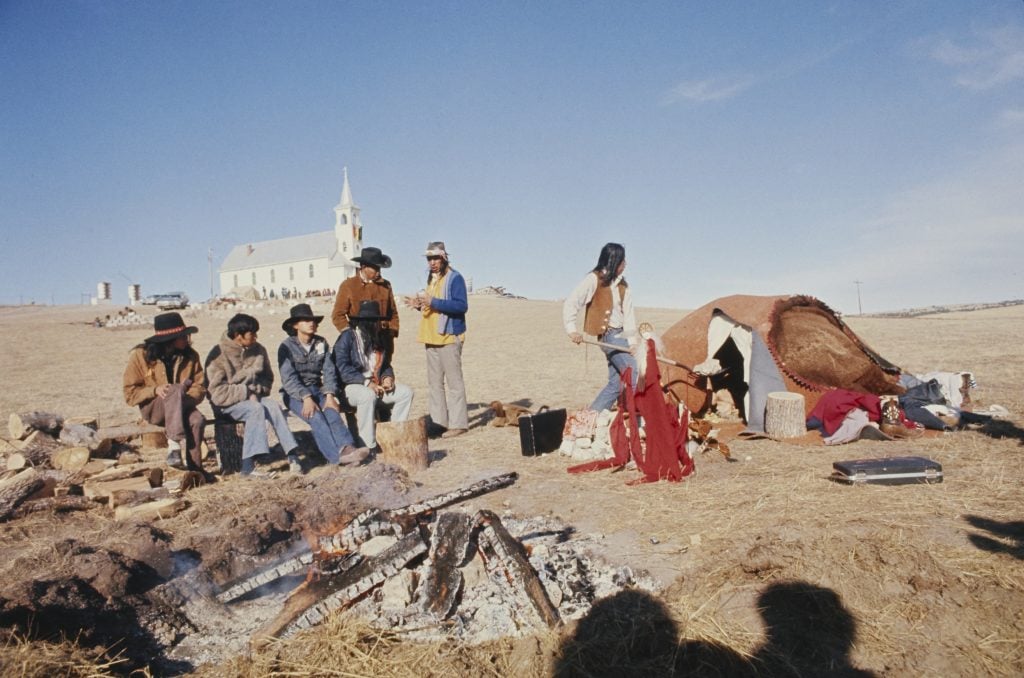

Carnage following the Massacre at Wounded Knee, 1890. Indian Wars, United States of America, 19th century. Photo: DeAgostini/Getty Images.

Soon after, on April 13, members of the Barre Museum Association voted during their annual meeting to continue with the repatriation efforts, under the guidance of a NAGPRA specialist, Dr. Aaron Miller.

In June, the museum had the artifacts tested for arsenic and mercury—dangerous compounds that were often used to preserve animal hides and feathers. Both were detected on the preserved relics, but not enough to impede their safe return. As part of following NAGPRA procedure, the museum also had all the artifacts photographed by the end of July.

This weekend, the museum finally welcomed representatives of the Oglala Sioux back to Barre for a public ceremony to return the items. The objects themselves were formally turned over in a private ceremony.

“We just wanted to do the right thing and help the Lakota people heal from the tragedy they suffered,” Meilus told Artnet News.

“Ever since that Wounded Knee massacre happened, genocides have been instilled in our blood,” Surrounded Bear, a 20-year-old Pine Ridge resident, told The Boston Globe. “And for us to bring back these artifacts, that’s a step towards healing. That’s a step in the right direction.”

Meilus estimated, however, that these 150 pieces are only a quarter of their Native American holdings, drawn from more than 60 tribes.

“Our collection is one of the most pristine collections of Native American artifacts in the country,” she said. “We have been told on numerous occasions that our collection beats the Smithsonian’s.”

More Trending Stories:

In a ‘Once-in-a-Lifetime’ Discovery, Swedish Archaeologists Have Unearthed a Cache of Viking Silver That Still Looks Brand New

Sarah Biffin, the Celebrated Victorian Miniaturist Born Without Hands, Is Now Receiving Her First Major Show in 100 Years

Disgraced Antiques Dealer Subhash Kapoor Handed a 10-Year Jail Sentence by an Indian Court

It Took Eight Years, an Army of Engineers, and 1,600 Pounds of Chains to Bring Artist Charles Gaines’s Profound Meditation on America to Life. Now, It’s Here

‘I’ll Have Terrific Shows Posthumously,’ Hedda Sterne Said. She Was Right—and Now the Late Artist Is Getting the Recognition She Deserved

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now