For the first time in nearly 100 years, Sarah Biffin, a Victorian painter who achieved artistic greatness despite being born without arms or legs, is the subject of a solo show, at London’s Philip Mould and Company.

“Sarah Biffin really was the most extraordinarily inspirational figure,” Mould said in a video promoting the show. “She overcame such challenges—her rural background in Somerset, the fact that she was a woman artist in an age dominated by men, and those extreme physical challenges. That she transcended to become a luminary in her profession, in this respect Sarah Biffin can be seen at the very forefront of female independence of the period.”

Born with a rare congenital anomaly called phocomelia, Biffin overcame her lack of limbs by learning to perform many tasks—including writing, painting, and sewing—with her mouth.

With few other opportunities available to a young woman with disabilities from rural Somerset, Biffin joined the circus, where she became known as “The Limbless Wonder.”

Her artistic talents were so great, however, that George Douglas, the 16th Earl of Morton, became her patron. (First, he sat for a portrait and stored it in between sittings to ensure no one else was responsible for the work.) The Earl arranged for Biffin to take lessons under the Royal Academician William Marshall Craig, at a time when women were not yet permitted to study at the London academy.

“Craig was recognized as an exacting draftsman on a small scale that suited her technique,” Mould said. “The impact of Craig upon Sarah Biffin was clearly profound. I mean, if you compare a self-portrait she did in 1812 with one done five or 10 years later… the distinction is so marked.”

Frances Cooper, Sarah Biffin at Bury Fair (1810). Collection of the South West Heritage Trust and Somerset County Council.

The exhibition includes nearly every known self-portrait of the artist, including one that recently achieved significant success at auction, when it went for the record price of £137,500 ($180,125) at Sotheby’s, London in December 2019. The result was remarkable considering its high estimate was just £1,800 ($2,360) and her previous auction record, unbroken for a decade, was just £2,040 ($3,383), according to the Artnet Price Database.

Philip Mould director Lawrence Hendra is said to have been an underbidder at the sale—no word on whether the gallery has since purchased the work, or if it is once again on the market in the current show.

Sarah Biffin, Young girl, standing, wearing a white dress (ca. 1812). Collection of the South West Heritage Trust and Somerset County Council.

But it was that sale that sparked the gallery’s interest in Biffin’s work, planting the initial seed for the current exhibition. The formal planning for the show began nearly two years ago, and involved securing loans both from private collections—including works that have never been published or publicly exhibited before—and institutions, where most pieces were not on view.

The gallery also enlisted the contemporary painter, Alison Lapper, who was born with the same condition as Biffin, to serve as as advisor on the exhibition.

Sarah Biffin, Self Portrait (ca. 1825). Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

“She seemed to transcend her disability and almost convince people that this wasn’t what it was all about,” Lapper told the Financial Times. “I’m still struggling now to break through the same barriers Biffin faced.”

In the course of research, Philip Mould and Company was able to track down many lost works after realizing that for some 20 years, Biffin painted under the name Mrs. Wright—her husband’s name. (The circumstances of the marriage are still being researched, but the gallery told the Guardian that its initial findings indicate that Wright was a fraudster, and may have absconded with his wife’s life savings.)

Sarah Biffin, Sarah Biffin Self Portrait Before Her Easel (ca. 1821). The watercolor on ivory sold for £137,500 ($180,125) on a high estimate of £1,800 ($2,360). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s, London.

A tireless and ambitious businesswoman, Biffin worked hard to promote herself, placing notices in newspapers, signing her works “without hands” to call attention to her unusual skill, and creating self portraits that advertised her abilities as a painter by surrounding herself with her wares and the tools of her trade.

“She was so canny and so commercially minded in a way that I don’t think women of the period are often really given credit for,” said Ellie Smith, a researcher at the gallery.

Self-portrait Sarah Biffin, Forget-me-not (1847). Courtesy of Philip Mould and Company.

Biffin’s clientele included royal and noble figures: King George III even appointed her as the miniature painter to his second daughter, Princess Augusta Sophia. And she was even immortalized in fiction, receiving several mentions in novels by Charles Dickens.

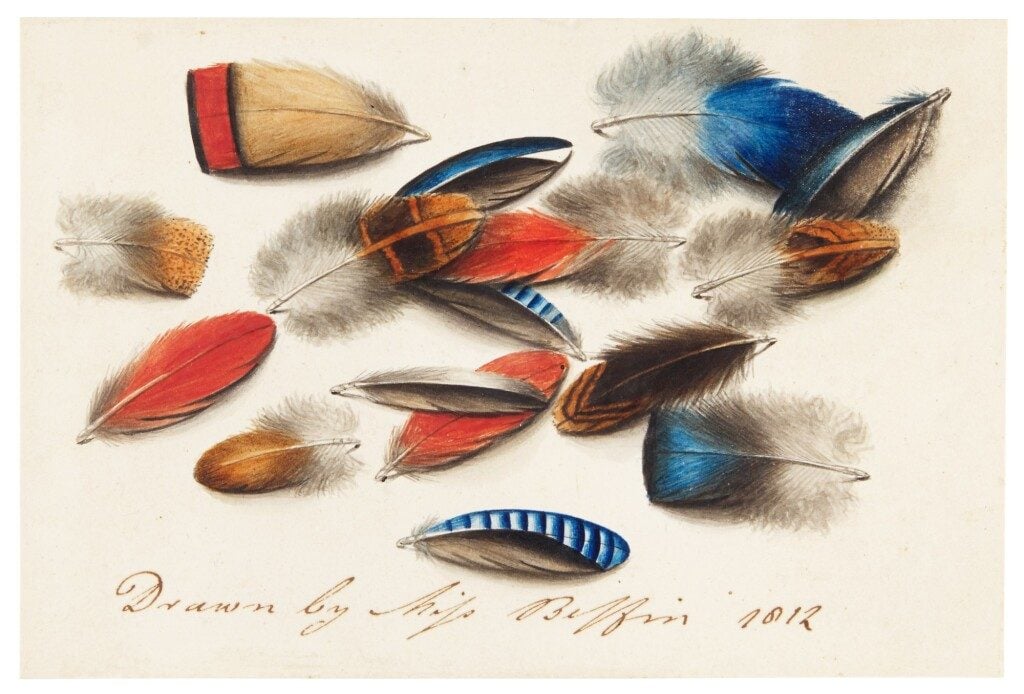

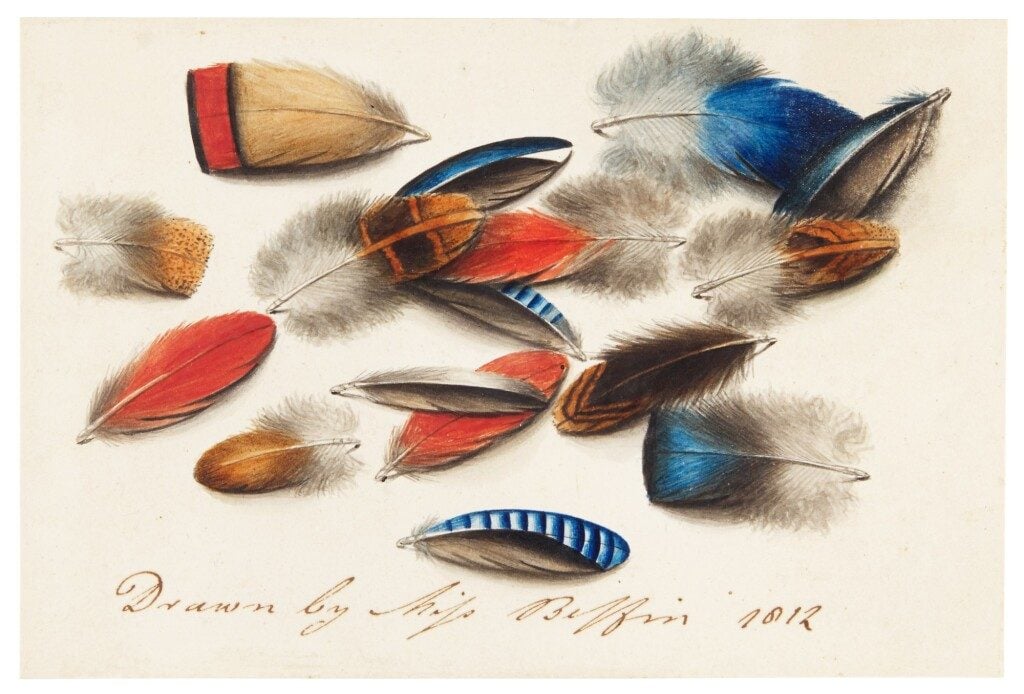

In addition to her prowess in portraiture, Biffin was also known for her hyperrealistic feather still-life paintings. The show includes her second-most expensive work at auction, Study of Feathers (1812). In July 2021, the watercolor sold for £65,520 ($90,335), crushing the £6,000 ($8,272) high estimate. (No word if Mould was the winning bidder that time around.)

Sarah Biffin, Study of Feathers (1812). The watercolor sold for £65,520 ($90,335), on a high estimate of £6,000 ($8,272). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s, London.

But regardless of market interest, the gallery believes that Biffin is artistically worthy of the renewed attention her oeuvre is attracting.

“This work is hugely accomplished. There is a fineness of detail, a quality of characterization,” Mould said. “This is exactly the sort of miniature that could hold its own in a highly competitive and crowded market of distinguished miniature painters.”

“Without Hands: The Art of Sarah Biffin” is on view at Philip Mould and Company, 18-19 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5LU, U.K., November 1–December 21, 2022.

More Trending Stories:

It Took Eight Years, an Army of Engineers, and 1,600 Pounds of Chains to Bring Artist Charles Gaines’s Profound Meditation on America to Life. Now, It’s Here

Mega-Collector Ronald Perelman Is Suing to Recover $410 Million for Art He Says Lost ‘Oomph’ After a Fire at His Hamptons Estate. His Insurance Companies Say It Looks Fine

A 28-Year-Old Who Unexpectedly Won a Dalí Etching at Auction for $4,000 Has Gone Viral With Her Rueful TikTok Video About It

Tom Hovey, the Illustrator Behind the Delectable ‘Great British Bake Off’ Drawings, on How the Show Has Catapulted His Career

The World’s Oldest Map of the Stars, Lost for Thousands of Years, Has Been Found in the Pages of a Medieval Parchment

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now