Art History

Francis Bacon’s ‘Screaming Pope’ Embodied Postwar Anguish—Here Are 3 Surprising Facts About the Influential Painting

The picture, Bacon's first of a Pope, is currently on view at the Royal Academy.

The picture, Bacon's first of a Pope, is currently on view at the Royal Academy.

Katie White

The facts of Francis Bacon’s life are the ones that tend to envelop interpretations of his work: he was an alcoholic, atheist, gambler, and homosexual in an intolerant age.

This fraught personalization is not so surprising given his subject matter. Bacon’s paintings are full of personal torment, depicting solitary figures with their faces and bodies writhing or contorted beyond familiarity, seemingly trapped in the empty, airless spaces that define his work.

The Royal Academy of Art’s just-opened exhibition, “Francis Bacon: Man and Beast,” aims to present the 20th-century artist’s work through a different prism: his fascination with the animal world.

While Bacon was very much a metropolitan louche in his adulthood, his childhood was immersed in nature. Born in Ireland to English parents, Bacon was raised on a horse farm (his father, a retired army officer, trained racehorses). The impressive exhibition brings together all of Bacon’s bullfighting paintings for the first time, as well as images of owls, a chimpanzee, and horse-like creatures.

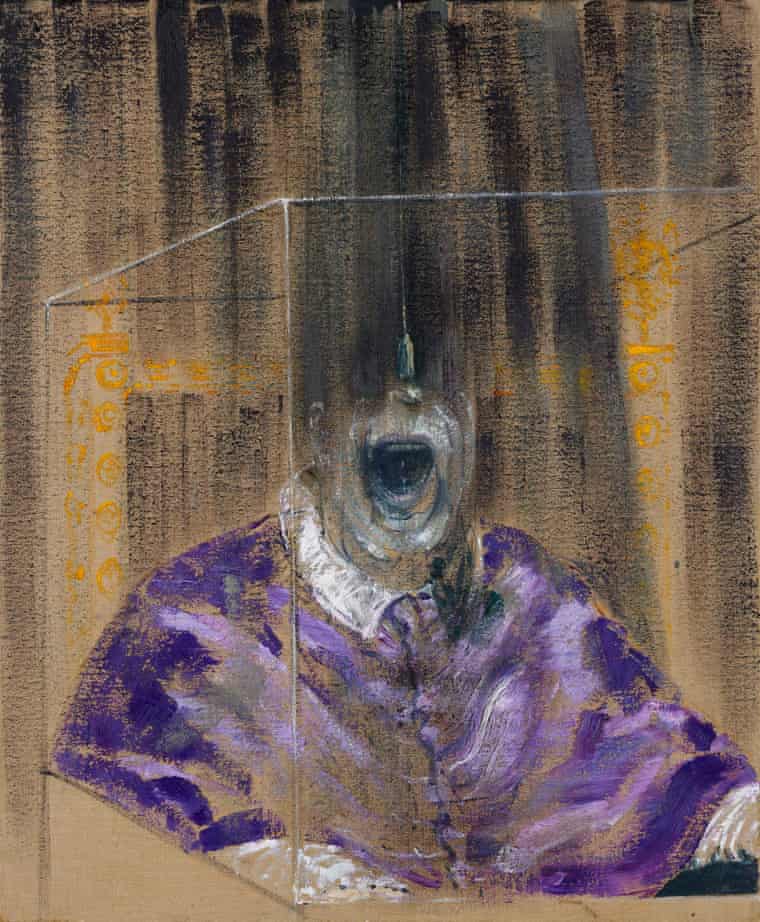

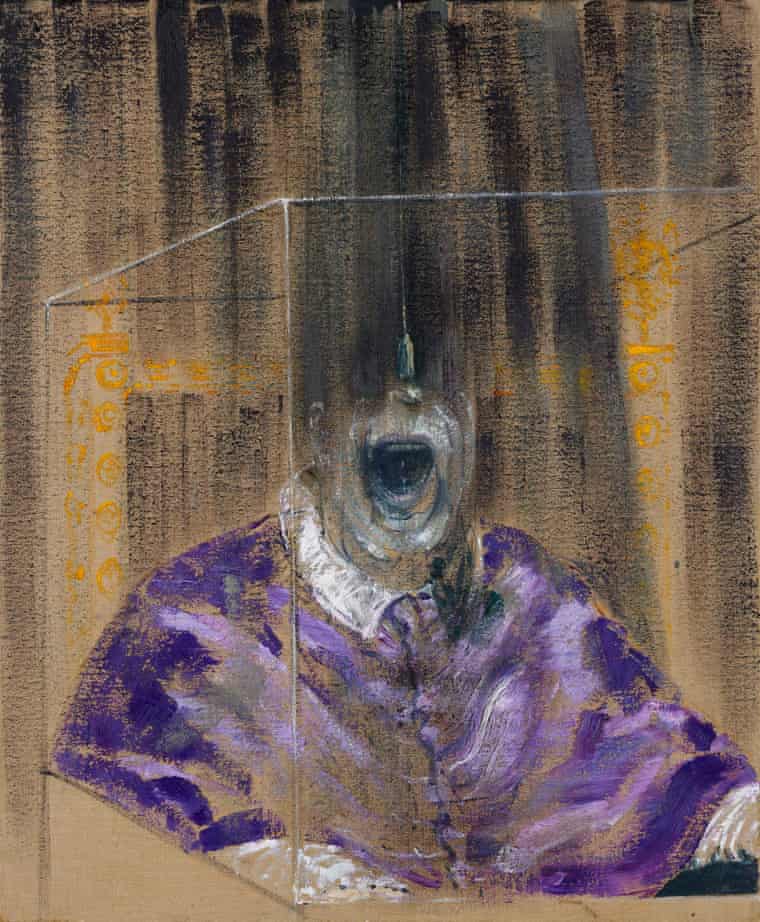

Several works in the show, rather than depicting animals directly, hint at humankind’s most primal nature. Among these is the seminal Head VI (1949), the first of Bacon’s paintings to reference Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X. (He would make close to 50 “screaming pope” paintings in his career.) The oil-on-canvas painting was the last of his 1949 “Head” series, and marked an important new chapter in the artist’s career.

On the occasion of the exhibition, we’ve unearthed three fascinating facts that might make you see the artist’s work in a new way.

Diego Velazquez, Portrait du pape Innocent X (1650).

While Francis Bacon was a devout atheist and an outspoken critic of the Catholic Church, his oeuvre is predicated on the iconography of Catholicism. This was the case from the very start of his career: the painting that defined Bacon as an enfant terrible of the art world was Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1945). (A secondary version of this triptych, made in the 1980s, is on view in the RA exhibition.)

Why did he return to the image of the Pope, and Pope Innocent X, so frequently? The word Pope shares its etymological root with the word “papa,” and many have interpreted Bacon’s fixation with the Pope through the Oedipal lens of Bacon’s tumultuous relationship with his father, who scorned both his son’s homosexuality and his desire to be an artist. In this vein, some have said that the “Screaming Popes” were a response to the Church’s teachings against homosexuality.

Others believe that Bacon’s fixation is rooted in his childhood, and his experiences living as a prosperous member of the English Protestant minority in Ireland.

“Bacon was brought up during the Sinn Féin movement and once the Irish Republican Army was formed in 1919 guerrilla warfare broke out. During his boyhood, Bacon’s understanding of religion was marked by social and religious tension and isolation,” writes art historian Rina Arya.

“These formative experiences led to a conflation between violence and religion, and by extension, the Pope, as the incarnation of the Catholic Church, would have been viewed within this context of opposition and conflict.”

Pope Innocent X, in particular, played a role in these historical tensions. During the English Civil War (1642–49), the pontiff acted is an important political player, offering significant arms and finances to support the Irish fight for independence in the hopes that it might establish itself as a Catholic-ruling nation. In such a way, the image so powerfully depicted by Velasquez embeds Bacon’s own experiences within a greater historical narrative.

Painter Francis Bacon in front of his paintings in Paris on September 29, 1987. (Photo by Raphael GAILLARDE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

One might wonder why a depiction of the Pope is featured in an exhibition focused on Bacon’s fascination with animals. A close examination of Head VI offers clues.

A clear box appears to surround the pope; such pictorial enclosures were a device Bacon adopted in 1949, and would reappear in his works for decades to follow. Many art historians have interpreted such enclosures as pens or cage-like structures, perhaps symbolic of society’s norms.

“His apes are usually caged, his dogs slink helpless and cringing from their broken leashes, and his humans are often segregated within small chambers or otherwise shielded from the ignored enemies of contemporary civilization,” writes art historian James Thrall Soby.

“Whatever its psychological implications Head VI announces with full vigor an abiding obsession of the artist: the enclosures within which animals and humans alike live out their lives,” he added.

The Royal Academy alludes to this synthesizing of man and animal in an exhibition text, saying: “Whether chimpanzees, bulls, dogs, or birds of prey, Bacon felt he could get closer to understanding the true nature of humankind by watching the uninhibited behavior of animals.”

Moreover, Bacon believed the mouth to be the most primal part of the human body. “You know how the mouth changes shape. I’ve always been very moved by the movements of the mouth and the shape of the mouth and the teeth. People say that these have all sorts of sexual implications, and I was always very obsessed by the actual appearance of the mouth and teeth,” the artist wrote.

If the Pope is traditionally believed to be called by the divine, here Bacon pictures him as though called by the wild.

Still from Sergei M. Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin.

“‘God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him,’ cried out the madman.”

While Frederic Nietzsche wrote those words about the death of Christian civilization in the 1880s, the experience of World War II had heightened belief in the proverbial death of God. It is here, in the immediate aftermath of war, into which Head VI’s scream is best understood. “Bacon’s interpretation is diametrically opposed to… sanctifications: it is, rather, located within the context of death,” Arya said of Head VI.

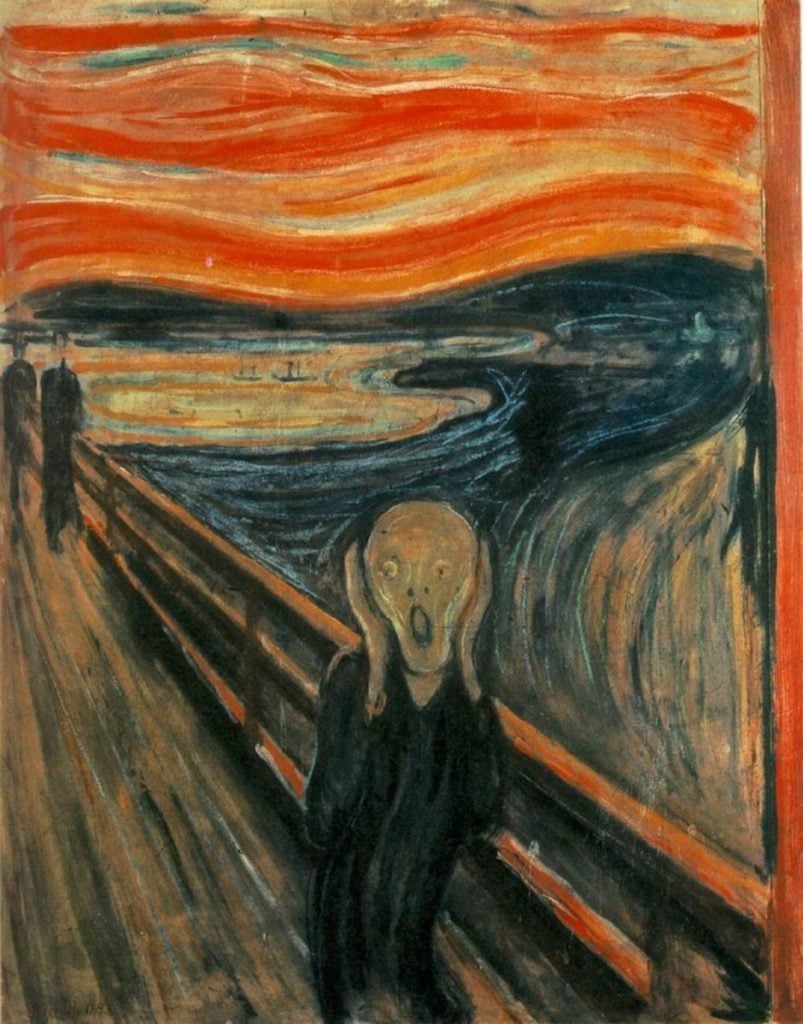

Bacon was a self-taught art historian and an avid cinephile, and his “scream” is one that exists on a continuum of cultural history. Bacon himself acknowledged that his image alluded to a scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925), in which a nurse silently screams after being shot through her glasses. (Bacon’s Pope similarly cannot be heard). While Bacon often tried to rebuff affinities between his work and that of Edvard Munch, The Scream is a self-evident influence.

“Bacon takes Munch’s kitsch Nordic universal scream, critiques it, and refines it. He gives it teeth… They express pain, the agony of orgasm, pity and terror, rage, appetite, fear, pleasure,” Craig Raine wrote in a 2016 article. (In the context of war, one also thinks also of Picasso’s Guernica of 1937, which was deeply influential to a young Bacon.)

Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893). Courtesy of the National Gallery of Norway.

It’s important to note that Bacon’s interest in the Pope came soon after he completed his 1946 Painting, a work laden with allusions to Nazism. A tassel (as though from a curtain) that appears in Painting returns in Head VI, creating a strange conversation between the two.

“The Pope’s head is bisected by the Hitlerian tassel… his mouth is agape in a scream… like in one of Goebbels’s more frenzied exultation,” notes Thrall Soby.

As the “Screaming Popes” continued, Bacon would insert increasingly direct references to contemporaneous pontiff Pope Pius XII, who some believe appeased the Nazis and who did not openly speak out against the Holocaust.

Considering Bacon’s Head VI in this context, Thrall Soby wrote: “In his paintings, an inexplicable sense of opulence prevails, and [curator] David Sylvester is right in saying that Bacon ‘prefers settings which are luxurious and simple lush velvet curtains and a gilded armchair like prison cells for high-born traitors.’”