Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Gift of Irving Blum, 1982. ©2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella Eskimo Curlew (1976)

Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon. Museum purchase:funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Howard Vollum ©2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Despite a career that spans six decades and one of the most prodigious and innovative outputs of any artist in history, it has been nearly 30 years since artist Frank Stella has been graced with a major US show.

That changes on October 30, when the Whitney Museum of American Art officially opens “Frank Stella: A Retrospective,” the first career retrospective devoted to a living artist at the museum’s new downtown digs on Gansevoort Street in New York’s Meatpacking District.

So why has it taken so long?

“First of all, it’s a huge career, just physically. How do you encapsulate it?” Michael Auping, chief curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, and primary curator of the show—in collaboration with Whitney director Adam Weinberg—told artnet News in a phone interview.

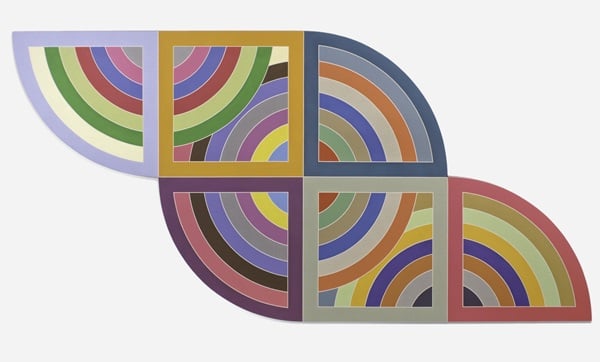

Frank Stella Harran II (1967)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Gift of Irving Blum, 1982.

©2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“It’s astonishing to me that these works were all made by the same artist over six decades,” said Weinberg on Wednesday, to a crowd of reporters at a press conference for the show, which consists of roughly 100 artfully arranged works that consume the Whitney’s 18,000-square-foot fifth floor.”If I told you this work was made by five different artists one could actually believe it,” said Weinberg.

Stella, who is now 79 years old, continues to spend most of his days in his studio. Auping notes the prolific nature of the artist, as well as his ability to take chances, saying, “There may be 40 different series of works, and within the 40 different series, there are many multiples of painting and prints. Over five decades obviously an artist is going to change tremendously and he did.”

Frank Stella, Die Fahne hoch! (1959).

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Stella first came to prominence in the New York art world during the 1950s, with a series of bold paintings that reflect his embrace of Abstract Expressionism; with his acclaimed Black paintings, executed with enamel house paint, he came to embrace minimalism. Ensuing series of aluminum and copper paintings in the 1960s featuring metallic paint and shaped canvases were also well-received by critics.

In later series, such as the “Polish Village” and “Moby Dick”—the latter of which featured a work from each chapter of the famous book—Stella’s experimentation with color, form, and material becomes ever more radical.

Frank Stella Grajau I (1975)

The Glass House, A Site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

© 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“If I were to summarize how most people feel,” says Auping, “they say, ‘I love the early work, the black paintings, copper and aluminum, the late work I don’t really know, I haven’t seen very much of it, I’m not as keen on that.’ And they’ve completely forgotten about the middle. Well, there is a lot of middle here,” he says, concerning the Whitney show.

Auping expects viewers to be pleasantly surprised, both by juxtapositions between series, as well as by individual works themselves they may have forgotten; at Stella’s insistence the organization of the show is “vaguely chronological,”he says. “I think there are going to be some real surprises in this show, such as the ‘Irregular Polyglots’..They’re big, they’re bold, they’re great.”

Similar activity in terms of interest in a wider range of works is also being seen in Stella’s market. While his work has certainly never lacked for demand and robust sales—the artnet price database lists more than 4,700 auction results and more than 40 of his works have fetched at least $1 million each at auction—demand has been intensely concentrated on earlier works, particularly the black paintings and concentric squares. But dealers say that is beginning to change.

The current auction record for Stella is $6.6 million for Abajo (1964), a shaped canvas with metallic powder and polymer emulsion that sold at Christie’s New York in May 2014, on an estimate of $6 million to $8 million. Sotheby’s is poised to break that record next week when it offers a Stella red concentric square painting Delaware Crossing (1961) from the collection of Alfred Taubman, that carries an estimate of $8 million to $12 million.

On the private side, extremely rare black paintings can fetch in the range of $35 million to $45 million, said New York dealer Marianne Boesky, who last year, in conjunction with Dominique Levy, largely took over representation of Stella. This was a key move for the artist, after years of showing with different galleries. (After showing with Leo Castelli for many years, Knoedler had been the longtime representative of Stella’s work until it abruptly shuttered in 2011 amid a forgery scandal).

Auction volume of works by Frank Stella, 1986 to 2015.

Source:artnet Analytics.

“There was no gatekeeper, and I think that’s something that’s super-important,” Boesky told artnet News in a phone interview. “You need scholarship around his work. There needs to be critical writing, and thought and attention and it also needs to be presented with clarity. To do shows with different galleries here and there…he was making fine sales, but there was nobody that was really kind of moving things forward.”

Boesky said she has already seen a spike in demand and prices for works from his “Polish Village” series. “We took a serious commitment to and interest in these works and people looked at me like ‘Yeah, I might give you $250,000 for one.’ Now, a year later, they sell for $1 million, and you can’t get them.” She continues, “If you put the right kind of clarity and import around them and you have the right group of people saying ‘hey wait a minute ‘look at this differently, it becomes a different conversation.”

Frank Stella, annual auction totals from 1986 to 2015.

Source:artnet Analytics

“The Whitney retrospective shows how clearly you get excited by works other than the usual suspects,” said New York dealer Paul Kasmin in a phone interview with artnet News.

Kasmin has known Stella for most of his life, since his father organized many of the artist’s early shows at his gallery, Kasmin Ltd, and has mounted several of his own shows, along with avidly following Stella’s output over the years. His most recent Stella show, “Frank Stella: Shape as Form” (September 10—October 10), featured groundbreaking works that fused sculpture and painting, from each of the artist’s key series.

Installation of “Frank Stella: Shape as Form” at Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Image: Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York.

“If you were to go out and buy a Frank Stella and you got excited by, lets say a 1980s Circuit painting, or Moby Dick sculpture, I think there’s true value to be had,” Kasmin says. “You can get a really nice Stella for between $500,000 and $900,0000,” which is relatively reasonable given his status as “a truly important Postwar American artist.”

Boesky thinks it behooves Stella to be presented in context with younger artists, particularly because of the enormous impact his work has had on younger artists. “He is the living source and influence of just about every artist in my program and maybe in any program,” says Boesky. “To be able to put him in a context where you can see his influence is different than being in a Knoedler context where he is, you know, the young one,” she says.

Last fall Boesky held a show of Stella sculptures at her New York gallery while Dominique Levy included important early Stella works in the transatlantic exhibitions “Local History: Castellani, Judd, Stella,” in New York and London.

“There are so many series that everybody is so familiar with,” says Boesky. “But the last 20 years or so and even a lot of the 1980s works, that are misunderstood or perceived as garish or overscaled, are so influential. I think they need to be spoken about in a fresh way in a context of the generations of young artists who are making work today.”

However, she doesn’t think its a negative that there is such a vast range of prices: “I actually appreciate that the market is particular. It shouldn’t be across the board that anyone just wants ‘a Frank Stella.'”

Belgian dealer Gregoire Vogelsang noted enthusiastic interest for Stella’s work a few months ahead of the Whitney retrospective, when he brought large-scale 1980s collages to Art Southampton priced in the range of $75,000. Vogelsang is bringing Stella’s works to the Contemporary Istanbul art fair this coming month, as well as inaugurating his second Brussels space this January with a Stella show.

And Spreuth Magers has just confirmed it will be representing Stella in Germany and Los Angeles going forward.

Stella’s strength is his continued passion for the work. As Boesky says, “Frank has always been three steps ahead, that’s what he’s interested in and he’s never cared about being popular.”