Art & Exhibitions

Berlin’s Contradictions Start Making Sense at Gallery Weekend 2015

In Berlin, grit and glitz go hand in hand.

Photo: Courtesy Duve Berlin

In Berlin, grit and glitz go hand in hand.

Hili Perlson

The 11th edition of Gallery Weekend Berlin saw hundreds of international curators, collectors, and art advisors making a weekend in the city the first leg on a long European haul that continues to Venice. But thousands of Berliners also flocked to the city’s art venues, which raised the question of how “democratic” should the Gallery Weekend be?

With some 47 participating galleries and numerous parallel events, the art crowds could practically design their own experience: discover new emerging artists or view museum-quality exhibitions; feel adventurous at provisional off-the-radar locations, or marvel at the sleek architecture of top-tier galleries. But as always in Berlin, partying all night was the unifying factor.

Even Berlin’s burgeoning foodie scene was making its mark: the army of art lovers that paraded down Potsdamer Strasse could enjoy oysters and wine at a pop-up stand located in the courtyard of the compound owned by Douglas Gordon, which houses galleries Sommer + Kohl and Supportico Lopez, as well as Tanya Leighton‘s showroom, Kaspar König’s office, and Gordon’s studio. Indeed, the weekend was all if not an image of a city in transition.

Berlin’s multiple identities as a place that’s constantly navigating polarities like past and future, gentrification and self-organization, or high-end and DIY, were mirrored in many of the exhibitions on view.

An excellent installation by Renata Lucas at neugerriemschneider looked at architectural periods visible in public spaces across Berlin. In the gallery’s backyard, Lucas erected a fountain that combines segments of several such structures: from Berlin’s oldest—the Triton (1888) in Tiergarten— to the GDR modernist aesthetics of Tanz der Jugend (1984) in the eastern district of Marzahn. Lucas’s multifaceted piece—divided along the middle through a metal partition—will remain in the yard until August.

Renata Lucas, fontes e sequestros (2015)

Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin Courtesy the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Generally, a host of solo shows by women artists offered some of the strongest art on view this year, though it doesn’t make up for the lacking representation of women in the city’s museums. In addition to our top recommendations, (See the Top 10 Exhibitions by Women Artists During Gallery Weekend Berlin) are also a slew of first solo shows in Berlin for ones-to-watch: Maria Taniguchi filled the main space at Carlier Gebauer with pieces from her ongoing series of brickwork painting; N. Dash presented her first solo show outside of the U.S. at Mehdi Chouakri; Haleh Redjaian showed arresting drawings and delicate wall installations at Arratia Beer; and Marguerite Humeau transformed gallery Duve using a toxic neon yellow paint—quite literally toxic, as it is mixed with poisonous venom.

“What’s it gonna be ‘cuz I can’t pretend; Don’t you want to be more than friends,” a gifted young performer approached a bemused Marc Spiegler with En Vogue’s hit Don’t Let Go (Love) just as he, and a group of people, entered the blooming garden at Johnen Gallery.

Both the plants and the performer were there as part of Tino Sehgal’s situation piece, which runs through June 6, and is not to be missed. The next evening, at the gala dinner in the Kronprinzpalais, rumors of Johnen Gallery and Esther Schipper negotiating a merge were spreading fast, and confirmed in a press release today.

Elsewhere in Mitte, a huge banner was stretched across the top of the Volksbühne theater, emblazoned with the word Verkauft (sold) in the house’s signature font. And though Chris Dercon’s new appointment as the theater’s director was the topic of conversation at several other dinner parties, Dercon himself wasn’t spotted at official events (see Chris Dercon Leaves Tate Modern To Direct Berlin’s Volksbühne Theater).

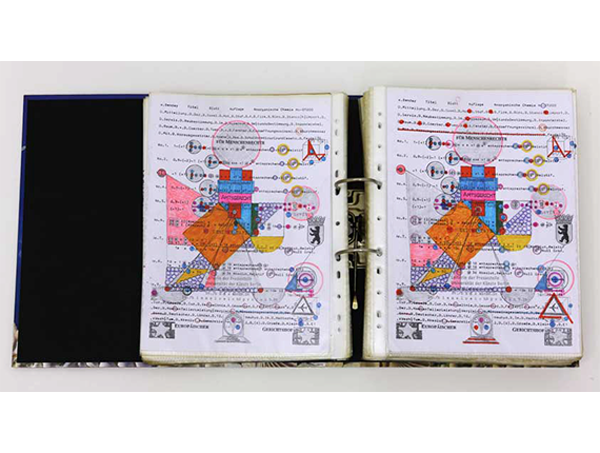

Adelhyd van Bender Ordner #33 (HB/Fol 0033) (1999–2014)

Photo: Courtesy Delmes & Zander

The cluster of galleries around the theater—an area that is somewhat of an unchanged stronghold—offered great shows. Among others, BQ had a silicon-filled show of new works by Bojan Sarcevic, and Galerie Nagel Draxler showed Kader Attia’s observations and variations on body modification, scarring, and injury.

Across the street, Delmes & Zander, who specialize in outsider art, showed works from the estate of self-named Adelhyd van Bender, a recluse who died of a cancerous tumour last year, which he considered to be a physical evidence of his feminine side. Adelhyd, who was kicked-out of Berlin’s art academy in the 70s, lived in his Schöneberg apartment among thousands of folders filled with thousands of pages filled with pseudo-bureaucratic insignia, scribbles, geometric color fields, and stamps. Can you help feeling nostalgic for a time where Berlin was full of strange birds rather than boys in Scandinavian brands?

Bojan Sarcevic Untitled (2014)

Photo: Courtesy the artist and BQ, Berlin

The weekend’s most striking ready-mades took central stage at two different shows, both tracing a Berlin story in their own way. Marianne Vitale installed a wooden American pioneer-era bar in the David Chipperfield designed space of CFA gallery. The work, which was her commissioned piece for Performa 2013, was the centerpiece of a show titled “Oh, Don’t ask why.” The line is taken from Kurt Weil’s Alabama Song, originally published as a poem in Bertolt Brecht’s Hauspostille (1927), who in turn, established the Berliner Ensemble theater, located just around the corner from the gallery. The song was famously covered by The Doors, but also by Berlin’s dearest former expat, David Bowie. For a city that’s constantly redefining itself, that’s the closest it gets to coming full circle.

Installation view of Marianne Vitale’s “Oh, Don’t ask why”

Photo: Courtesy CFA Berlin

Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler showed Daniel Keller’s multilayered musings on alternative yet formally binding models of relationships, namely as a registered LLC rather than ordained marriage. Green spirulina algae was self-efficiently multiplying in aquariums arranged around a large free-standing glasswork. The ready-made was originally a windowpane of a swanky new condo in Kreuzberg, located across the street from a trailer park inhabited by punks. Talk about non-conformist ways of life.

The windowpanes got smashed by anti-gentrification activists and repaired time and again, until Keller purchased them in exchange for their replacement. The press release describes the artist’s act as simultaneously “accelerationist, Kintsugi, and Duchampian.”

The one event on everyone’s lips, however, was Ngoro Ngoro, a so-called “Artist Weekend” initiated by artists Jonas Burgert, Christian Achenbach, Zhivago Duncan, Andreas Golder, John Isaacs, and David Nicholson, at their 5,000 square meter studio space in a disused GDR-era factory in Weissensee. The weekend-long exhibition included works by more than 130 artists, and was always full. Klaus Biesenbach was a fan of the chilled-out atmosphere and kept Insagramming from the site—which also included a sausage stand, a bar, and a swimming pool—almost every day.

Klaus Biesenbach kept Instagramming from the Artist Weekend event, Ngoro Ngoro

Photo: via instagram.com/klausbiesenbach

Should Berlin be more like this? Less regulated? Not so stiff? Well, yes and no. It wasn’t so long ago that DIY events in derelict factories were the rule, and “professionalization” the exception. That Berlin needs both became most clear after a visit to the Michel Majerus Estate in Prenzlauerberg.

Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen organized a show at the late artist’s estate, titled “best students, best teachers, best school,” with works by Michel Majerus, Albert Oehlen, and Laura Owens (who was also showing new paintings at Capitain Petzel).

Two works by Oehlen featured a black silhouette of a tree against a red and white background, an unusually figurative offering from the German painter. But it wasn’t until you saw a small installation by the artist in a small Mitte apartment, that the paintings truly began to unfold. In a tiny room in the office-apartment of art-and-music label Bureau Müller, Oehlen stuck an upside-down branch in a pile of sand, and shone an haphazard spotlight on it, that was partially covered with a red transparent sheet. The whole construction is operated by pressing a button, which also turns on the track, composed by the artist. The shadow on the wall resembles a resourceful, makeshift version of the large-scale paintings. Indeed, the one wouldn’t be the same without the other.