People

‘Most Black Film Isn’t Allowed to Be Ambiguous’: How Garrett Bradley’s Quiet Documentaries Found a Rapt Audience in the Art World

The artist was awarded best director at Sundance and has a solo show on view now at MoMA.

The artist was awarded best director at Sundance and has a solo show on view now at MoMA.

Melissa Smith

The thing is: Sibil and Robert Richardson were guilty. But that didn’t dissuade filmmaker Garrett Bradley from telling their story.

Director Ava DuVernay recently asked Bradley why her celebrated documentary, Time—which tells the story of Sibil’s fight to get her husband Robert out of prison—doesn’t explicitly address America’s criminal justice system.

“What brought me to making this film,” Bradley replied, “wasn’t so much those big issues as it was… leaning into the intimacy and beauty and strength of what I saw in [the subjects] as individuals.”

One of the hardest parts of being an artist is finding the right story to tell. Bradley’s priorities and instincts—which, to a certain extent, have been lived and not learned—led her to focus first on the Richardson family, with the rest of the narrative falling into place from there.

This approach is emblematic of 35-year-old Bradley, who is quickly becoming a force in both the art and cinema worlds.

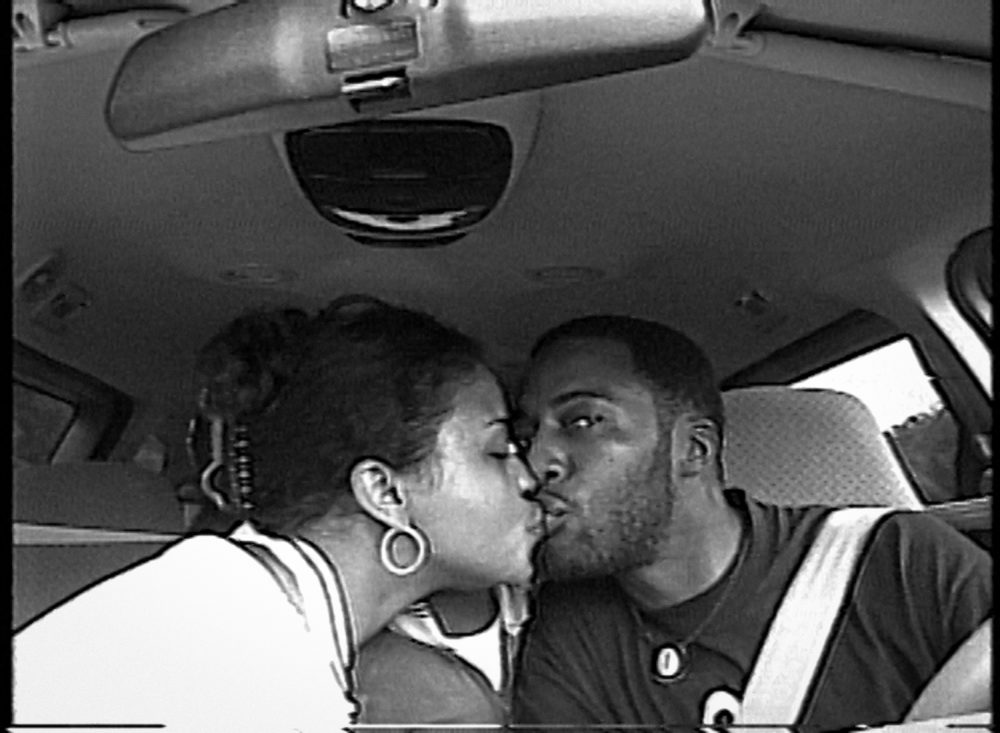

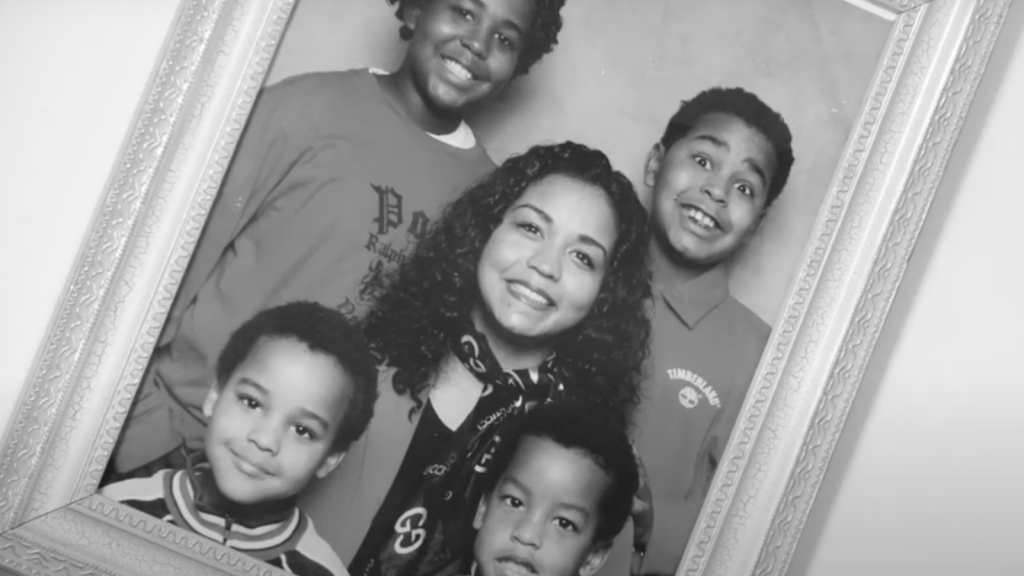

Still from Garrett Bradley’s Time (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Amazon.

Time, now streaming on Amazon, has won nearly every award for which it’s been nominated (including best director for Bradley at Sundance). It captures the life of Sibil, better known as Fox Rich, who, along with Robert, made a botched attempt to rob a bank in the late ‘90s. Sibil, who was 16 at the time, was sentenced to three years in prison; Rob was released in 2018 after serving a 21-year sentence.

When Bradley considered adding details about our prison-industrial complex to Time, she essentially found herself trying to “explain racism in America,” she told DuVernay, “and then that made me ask myself: Well, who is my audience? Do I need to explain racism? Or do I just trust that who I’m speaking with is just going to understand what’s going on?”

Bradley was born in New York in 1986 and raised by two artists. She made her first movie in high school. Her teacher told her it was good—so good that she encouraged Bradley to submit it to a festival at her school, Brooklyn Friends. Academics never came easily to Bradley, who has dyslexia, so when she excelled at something, she thought, “I’m not doing anything else. This is what I’m doing now for, like… forever.”

The film, which Bradley describes as “a little thing made with her school’s camcorder,” was centered on her parents, who divorced when she was two. Through the film, she wanted to get to know her father a little better—both individually and through his relationship with her mother.

Before spending any more time going into detail about the movie, though, Bradley quickly warns me not to assume she had been “affected in any kind of way by their divorce.” It felt as though she sensed where my mind would go; that, when left with no context, people tend to fill in the gaps—just like I was about to—with the easy story, but not necessarily the right one.

Still from Garrett Bradley’s Time (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Amazon.

This is classic Bradley: she seems to have the ability to recognize someone else’s tendency to make quick—and oftentimes false—assumptions, but not succumb to the same. In her work, she allows narratives to naturally progress rather than forcefully shaping them, and that’s rare. This openness was especially evident when, at the tail end of shooting Time, Fox Rich handed her more than 100 hours of archival footage of herself and her family, recorded over the 21-year period of her husband’s incarceration.

With that, the film immediately transformed from a short into a feature—one that is neither strictly documentary nor strictly fiction. “One of the things that’s most interesting about her as an artist,” notes curator Rujeko Hockley, “is that she’s really destabilizing a lot of these categories that we place around types of moving image-making.”

Bradley’s work began to gain widespread notice in 2014, when she debuted her first feature, Below Dreams, about three millennial strivers in New Orleans, at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Around the same time, she was busy filming 12 short vignettes as part of a project to reimagine Black feature films that could have been produced between 1915 and 1926—a period during which, according to the Library of Congress, 70 percent of the films made in America have been lost.

Bradley arrived at the idea after reading about the Museum of Modern Art’s unlikely discovery of footage from what is believed to be the earliest feature film with an all-Black cast, Lime Kiln Club Field Day. Could there have been more of these Black-made movies, Bradley thought?

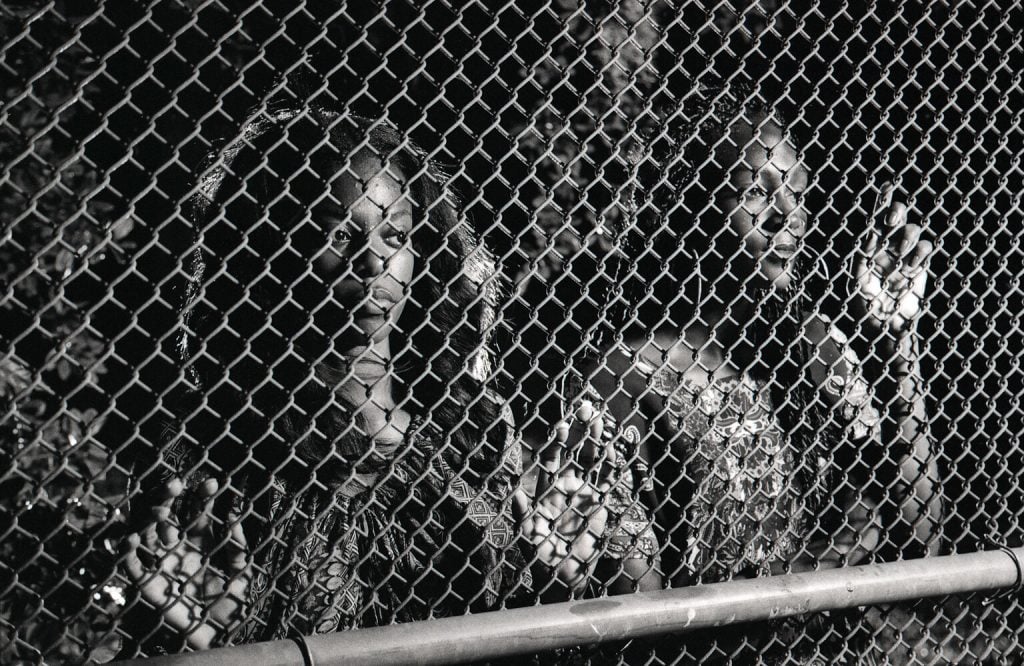

Garrett Bradley, America (2019). Courtesy of the artist and MoMA.

“They found this one film that happens to be in this period that’s super progressive,” Bradley says. “What would it mean to fill that gap with the assumption that all this work was equally as progressive—socially and cinematically—as what we see in Lime Kiln?”

This line of thinking turned into America (2019), a multi-channel video installation on view at MoMA (through March 21). In it, Bradley intersperses scenes from Lime Kiln with the black-and-white films she began shooting and remixing years earlier.

“America was my first time really trying to investigate and work through archives… something that I did not have control over,” she says. Bradley joins a cohort of filmmakers and artists, like Ja’Tovia Gary and Bisa Butler, who are, in different ways, mining the historical archive and looking for ways to responsibly insert Blackness into it.

Garrett Bradley, America (2019). Courtesy of the artist and MoMA.

She, along with these other artists, is addressing something that is “bigger than truth at this point,” says City College of New York film professor Michael Gillespie. “It might sound hackneyed or tired to say it, but there’s a measure of a political consciousness-raising that’s happening.”

After beginning with a few stills from Lime Kiln featuring its black-faced star, Bert Williams (who, mind you, was already Black), America features a scene of a white man sitting beneath a tree with a white sheet draped around his body. A Black woman quietly moves towards him, takes off her hat, violently grabs the sheet and fights him for it. Then she cooly returns her hat to her head and walks away.

This was one of Gillespie’s favorite parts. “I always think of that as a great reading, thinking about the history of the Birth of a Nation,” he says, referencing the horrifically racist 1915 film that glorified the Ku Klux Klan, “and just how quickly he can be disrobed and we can just keep on moving down the road—that that doesn’t necessarily have to be the beginning of the story, it’s just one point along the way.”

Installation view, Garrett Bradley, America (2019) at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Photo: Will Michels.

America moves through a carefully crafted chronology of historical events, with some that represent Blackness and others that do not explicitly—but Bradley feels still can. There’s 1915, when Birth of a Nation was screened at the White House; 1916, when Woodrow Wilson established the Boy Scouts, which Bradley re-envisioned using students she’d taught at the Sojourner Truth Neighborhood Center in New Orleans; August 2, 1974, the day James Baldwin was born and New York City held its first-ever Macy’s Day Parade.

This kind of melding of real events with reconstructed scenes represents an evolution in thinking about film and the role it plays in establishing the Black image. Each of us carries a set of preconceived ideas about the truth in history, the truth in life. With America, Bradley began to understand how incomplete and disjointed that truth can be, not only in our archives but also “in this present moment,” she says.

After making that work, she was able “to take it a step further,” she continues, “in working with a contemporary archive with a living person, with Time.”

Still from Garrett Bradley’s Time (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Amazon.

Bradley accepts her subjects for who and what they are—so much so that she brought in Fox Rich as a co-creator of Time. The film operates “within a community, and incorporates the community,” says Yale media studies professor Thomas Allen Harris, who considers Bradley’s work as part of a lineage that includes Camille Bishops and William Greaves.

Like America, Time thrives on ambiguity, on showing how a story about Blackness doesn’t have to fit into a neat package to be a story worth telling. “Most Black film isn’t allowed to be ambiguous,” Michael Gillespie notes, because “it has to provide immediate answers on how to save Black people.”

On top of that, films about systemic racism often highlight Black pain and trauma first and foremost. Those that bluntly spell out what is wrong with the “system” tend to be judged only on how well they fight the “good” fight—rather than on their creative merits. By contrast, Time isn’t intended to convince an external audience of much of anything.

“It was beautiful that the film wasn’t interested in trying to traumatize,” says Darius Monroe, who is very familiar with how audiences react to films about incarceration, having made one about his own called Evolution of a Crime.

Garrett Bradley, America (2019). Courtesy of the artist and MoMA.

By taking away “things that normally would be included, like the court case, and jail,” Thomas Allen Harris says, Bradley brings us “into this other world and we then get this validation of that world.”

Not the world of prison. Not the world of Fox Rich and prison. Just Fox Rich and the poetry of her family’s world.

In the end, history—and life—will never be a singularly understood set of facts. The truth will always be how we are willing to see it.

Of the 7,500 films missing from the Library of Congress, “we’re starting with 12,” Bradley says in reference to America. “It’s my dream that one day we would be able to create some kind of fund for other artists and filmmakers to continue to make films in the spirit of these parameters, until we collectively have filled that gap.”

In all of her work, Bradley is providing audiences with an opportunity to let go of their sense of context. Because without letting our expectations get in the way, it all seems so simple to her. “When something touches you, it touches you,” she says. “It’s really not that deep.”