How do you deal with a problem like Gauguin? Curators are grappling with the issue more openly than ever in a major exhibition that acknowledges the French artist’s sexually predatory behavior in the South Pacific.

The poster child of the show “Paul Gauguin Portraits,” which has just opened at London’s National Gallery, is the artist’s portrait of his Tahitian mistress, Teha’amana a Tahura. It may shock some visitors to learn that she was probably 13 years old when she became the much older artist’s “wife.”

The exhibition, which the National Gallery co-organized with the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, where it first opened, coincides with the second anniversary of the #MeToo movement. Gauguin exhibitions until very recently have focused on his greatness as a Post-Impressionist. This is the first time that such high-profile institutions have broken a curatorial taboo to also discuss his flaws as a man.

“Gauguin undoubtedly exploited his position as a privileged Westerner to make the most of sexual freedoms available to him,” a wall text states midway through the show. The publication accompanying the exhibition places his behavior in the South Pacific in its historical context. In the 1890s, “a young Tahitian woman would not have knowingly lived with a married man,” suggesting that Gauguin kept his Danish wife and family back home a secret.

Gauguin’s infidelity to his wife, Mette Gad, who he left back home in Europe to help sell his paintings, has long been known by art historians and curators, as well as his predatory behavior in the South Pacific and in Asia. Upon his return to Paris, his dealer Ambroise Vollard described the artist as an “Oriental prince,” with a Javanese girl in attendance.

“Even five years ago when we started working on the exhibition we realized that things had moved on, and that we would need to address these issues,” says Christopher Riopelle, the National Gallery’s curator of post-1800 paintings, who has co-organized the show with guest curator Cornelia Homburg of the National Gallery of Canada. “Formal analysis [of paintings] cannot occlude the real issues,” he says.

The National Gallery is also opening itself up to a debate about how it should show Gauguin’s art in the light of the #MeToo movement. Questions such as: “Can we still love the work of artists whose behavior we loathe?” and “Do Gauguin’s artistic achievements justify what he did to underage women?” will be debated this Friday, October 11, at a discussion organized by the National Gallery. Speakers include scholars and writers, including Janet Marstine, an honorary associate professor at the University of Leicester’s school of museum studies and the co-editor of forthcoming publication Curating Under Pressure.

Marstine calls the Gauguin exhibition “an important first step” for a national gallery. “They want to be responsive to the contemporary context,” she says, adding, “if they are not, they may well be held accountable.” Marstine adds that, increasingly, the ethics of a museum are being judged in part by the way “they navigate the ethics of the artists they are exhibiting.”

Jackie Wullschläger, art critic for the Financial Times, did not pull any punches in her review of the show. In reference to one of the show’s highlights, Gauguin’s Self-Portrait with Manao Tupapau (1893-94), which is on loan from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the critic refers to Nabokov’s anti-hero in Lolita, describing Gauguin’s self-image as being “as sinister a Humbert Humbert prowling new world as ever envisioned in paint.”

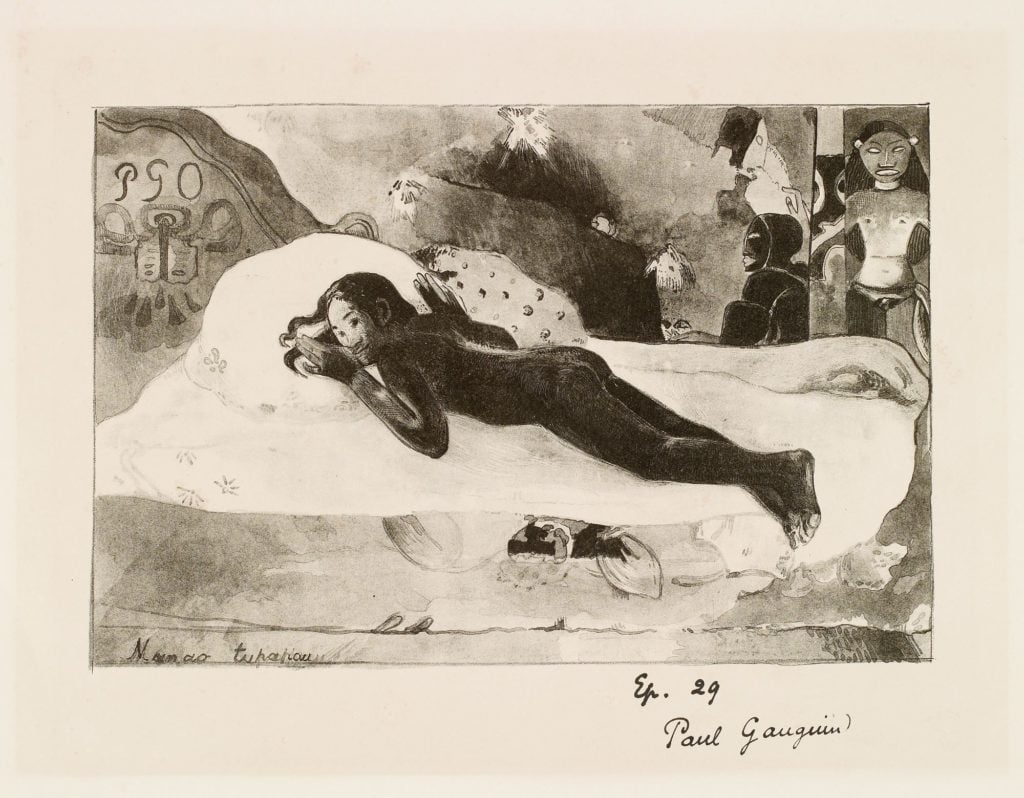

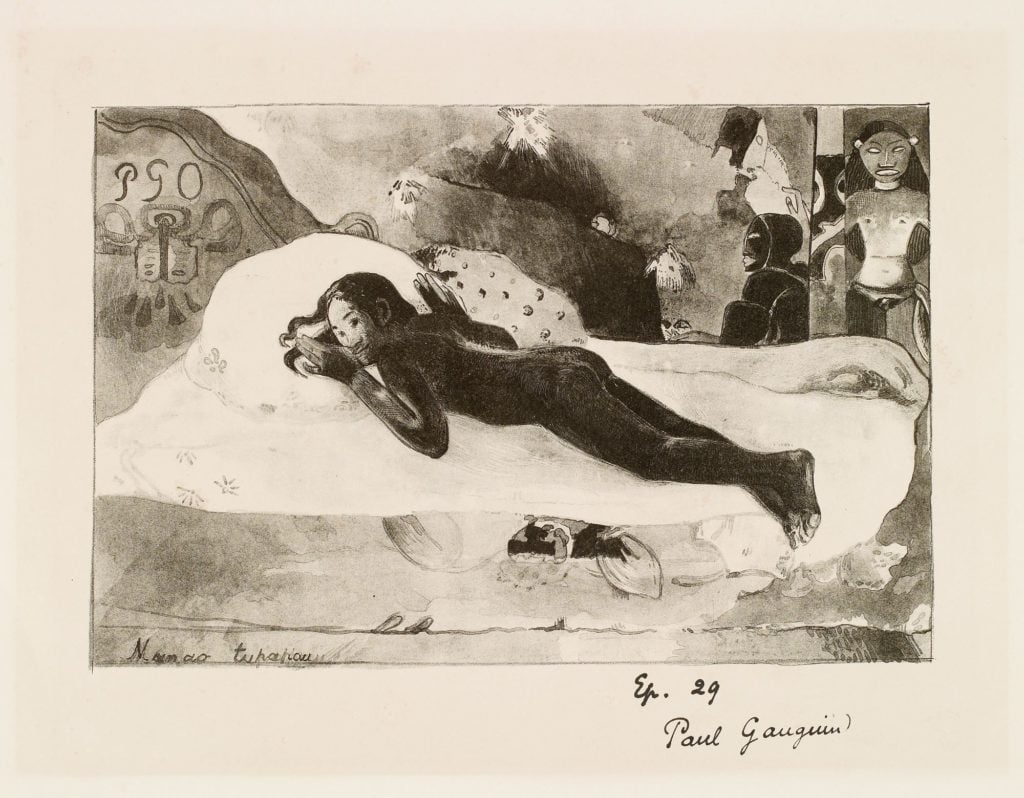

Paul Gauguin Manao Tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Watching) (1894)

Lithograph © National Gallery of Canada.

Hanging on the wall in the background of the self-portrait is the artist’s own nude painting of his underage Tahitian mistress, Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Watching (1894), a work that is now in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Gauguin’s lithographic print of that controversial nude hangs nearby in “Gauguin Portraits.” It is an alluring but unsettling image. The exhibition caption euphemistically states that the painting is “one of his most disturbing portraits.” The publication downplays Gauguin’s possibly abusive relationship with the girl, stating that the composition suggests “as if both her body and soul are at risk of assault” from disturbing spirits.

In her essay on Gauguin’s portraits that feature his young Tahitian mistress, Elizabeth C. Childs, a professor of art history at Washington University in St. Louis, speculates that his many depictions of Teha’amana “can best be understood more as reflections of his self-exploration and his artistic process in the face of engaging—but to him exotic—subjects than as direct records of personal encounters with a particular woman.”

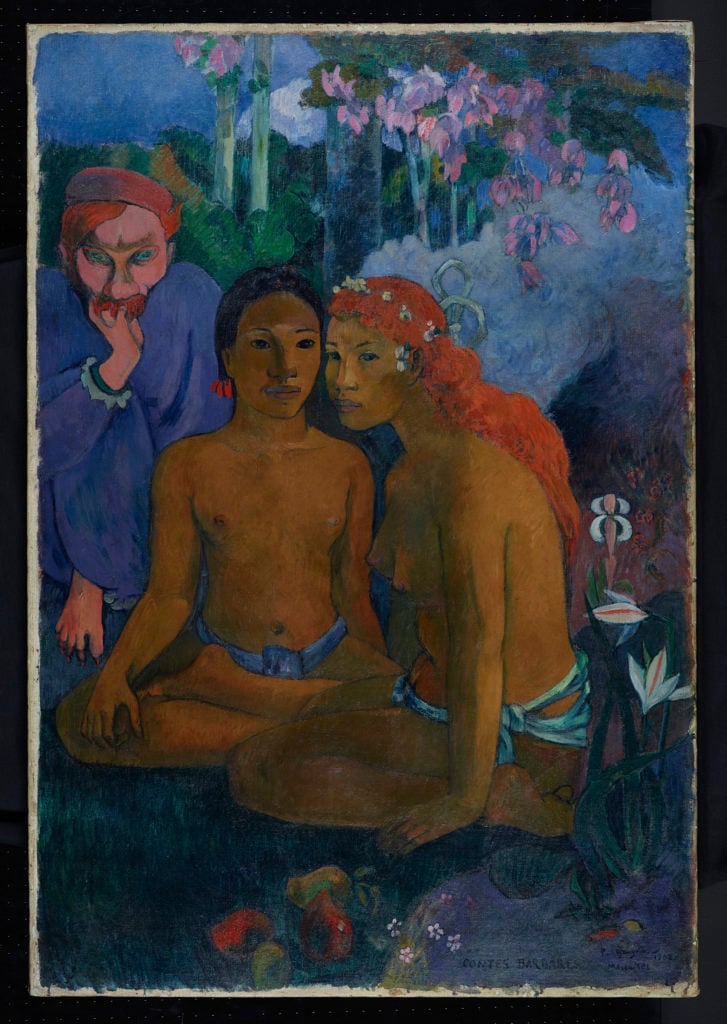

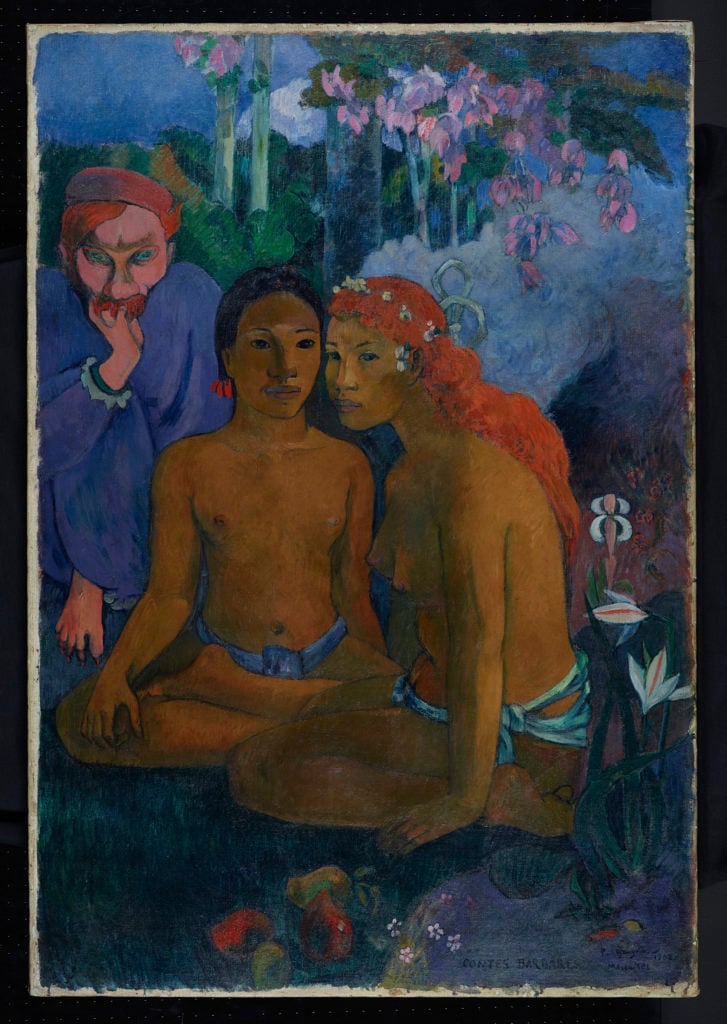

Paul Gauguin, Contes barbares (1902). Courtesy of the Museum Folkwang, Essen.

The exhibition’s star loan is Gauguin’s last major painting, Barbarian Tales (1902), from the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany. It features two girls from the Marquesas islands. Painted a year before he died, at age 54, the syphilitic artist included a diabolical figure in the background based on his long-dead friend back in Paris. The wall text in this room reverts to type, merely noting that Gauguin “started new relationships with local women,” and called his studio hut the “House of Pleasure.”

The National Gallery of Canada edited several wall texts and picture captions during the Gauguin exhibition in Ottawa, artnet News has learned. A spokeswoman says changes were made to the texts about the artist’s relationship with young female models. “We wanted to be clearer about the power dynamics involved,” she says, adding that edits also concerned “Gauguin’s colonial and patriarchal privilege.”

Speaking in general about the issue confronting art museums as they carefully word their texts, Martine warns that art institutions can risk sending mixed messages, if their approach to an artist’s problematic biography is too tentative. She cites the Ditchling Museum in the South of England as a good example of how to reframe works by an artist who was a serial sexual abuser. In its 2017 exhibition on British artist Eric Gill, whom art historians have long known abused his own children, the museum grappled with whether you can separate the artist from the abuser. “They helped viewers to make their own ethical decisions and shared some of the difficult conversations staff had to devise,” Marstine says.

Reflecting on how art museums have belatedly addressed artists’ behavior, even when it was reprehensible in their own day, Rioppelle says: “There was, at a certain point, a hope that art could remain a separate elevated realm, but now we realize more clearly that it has all the complications and unappealing aspects of real life.”

“Paul Gauguin Portraits” October 7 through January 26, 2020, National Gallery, London