In a review of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s landmark 2002 exhibition of quilts from Gee’s Bend, New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman described the textiles as “some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced.” The quilts, he wrote, were “so eye-poppingly gorgeous that it’s hard to know how to begin to account for them.”

Since then, these dazzling geometric artworks have traveled around the globe, been reproduced on official US postage stamps, and become broadly recognized as an important part of American art history.

But back in Gee’s Bend—the tiny Alabama hamlet formally known as Boykin that has nurtured three generations of quiltmakers—the impact of the quilts’ renown has been more subtle.

According to the most recent US Census, 20 percent of the area’s roughly 300 residents, a significant number of whom are active in the quilting community, live below the poverty line. The median annual household income is under $16,000.

A visitor looks at the “Quilts of Gee’s Bend” exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in February 2004. Photo: Stephen Jaffe/AFP via Getty Images.

“We don’t have a store, a gas station, not even a red light down here,” Mary Margaret Pettway, a third-generation quilter and Gee’s Bend resident, tells Artnet News. “If you came down, you’d be hard pressed to try to leave money [behind], even if you wanted to.”

That may soon begin to change, however. A new initiative spearheaded by Souls Grown Deep, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting the work of African American artists from the South, aims to transform Gee’s Bend into a tourist destination.

“It’s a thriving community that continues to create,” says Raina Lampkins-Fielder, the curator of Souls Grown Deep. “We’re looking at why these artists might be disenfranchised to ensure they find their rightful place within the canon, but also that they are supported on the ground level.”

The thinking goes: If Marfa, the pint-size Texas town located a three-hour’s drive from the nearest airport, can become a site for pilgrims seeking to commune with Donald Judd’s Minimalist art, why can’t Gee’s Bend become a magnet for art historians, craft enthusiasts, and American history buffs who want to know more about the source of the world’s most acclaimed quilts?

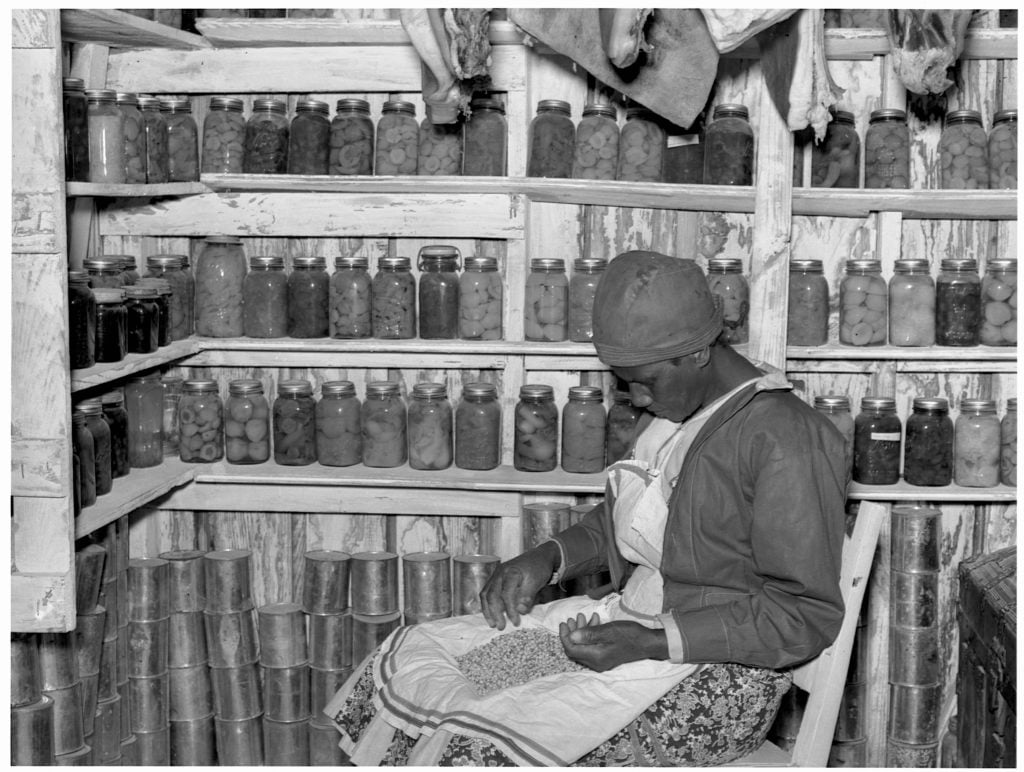

Quilters at Gee’s Bend. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images.

Opening Up the Bend

A series of initiatives, some of which have been in the works for years in collaboration with local residents, will be formally announced today. The first is a collaboration with Nest, a nonprofit that promotes handmade crafts, which will work to make Gee’s Bend quilts more accessible for purchase online and enable Gee’s Bend quiltmakers to license their work for reproduction. Additional projects may include the development of a cultural center, a hub for quilting workshops, a marketplace for locally sourced goods, walking trails, cottages for people to stay, and community-run Airbnbs.

The project also includes funding to maximize local participation in the 2020 census (including providing public internet access so community members can fill out the forms online), which organizers hope will allow the historically under-counted population fairer access to federal resources. Another important component is resurfacing the history of individual quilters. Even when the US Postal Service released its Gee’s Bend stamps in 2006, Lampkins-Fielder notes, the artists were not identified by name.

A view of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, which is formally known as Boykin. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images.

“There has been this tendency of just grouping the quiltmakers as ‘the quiltmakers’ and not naming them as individual artists, which flies in the face of what is done in museums,” she says. To address this oversight, the organization will work with quilters, their families, and the leading graphic design consultancy Pentagram to revive and expand the Gee’s Bend Quilt Trail, which marks the homes of leading quilters.

Lampkins-Fielder says that Souls Grown Deep’s work in Gee’s Bend will have an impact not only on the community itself, but also on a chapter of art history that remains under-explored. Better known Southern artists, such as Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley, for example, were aware of and inspired by the work of the Gee’s Bend quilters—connections that scholars are only just beginning to examine.

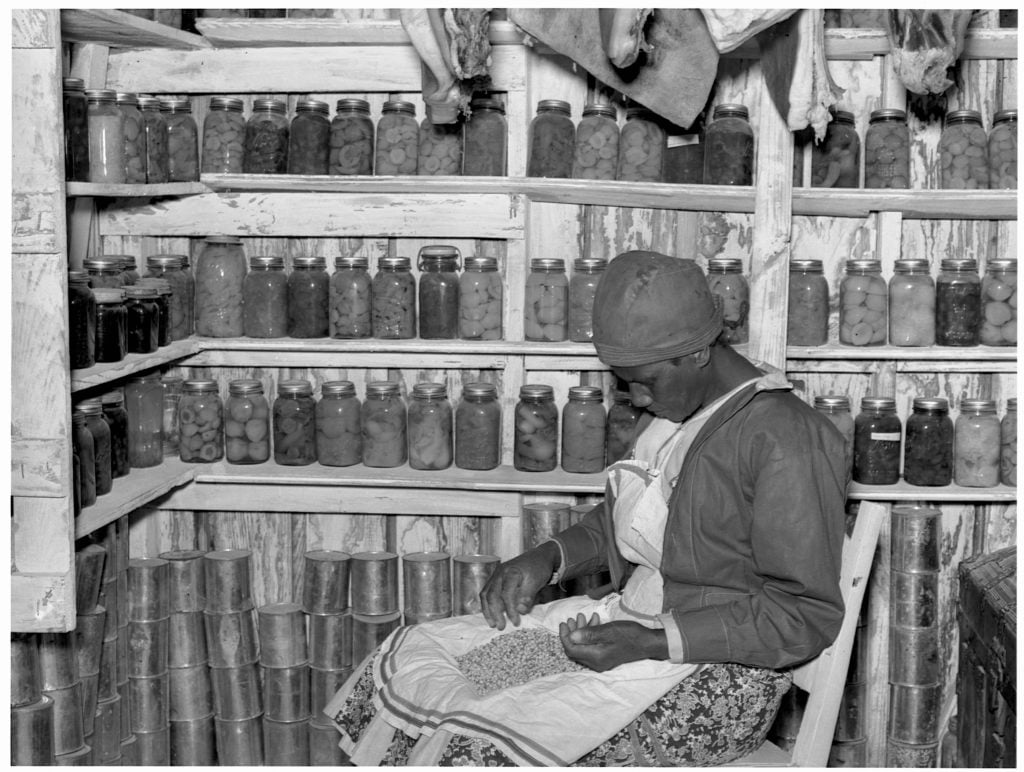

Jorena Pettway, a Gee’s Bend resident, sorting peas inside her smoke house with last year’s preserved fruits and vegetables on the shelves around her. This photo was taken in May 1939. © Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images.

An Uphill Battle

No transformation of Gee’s Bend would be easy. For decades, the small hamlet has suffered from poverty and isolation, which is partly a product of geography: the community is nestled in a literal bend in the Alabama River and is surrounded by water on three sides, making it almost an island.

But its isolation is also a function of systemic racism. The first paved road leading into and out of town was laid down in 1967—around the same time that ferry service was suspended in an effort to keep the local black population from crossing the river to register to vote.

Ferry service was restored in 2006, but most Benders must still drive hours to get to and from their jobs. (When we spoke, Pettway was on her way back from dropping off her daughter at work an hour away.) “Right now, there are very few jobs here [in Gee’s Bend],” says Pettway, who is also Souls Grown Deep’s board chair.

Initiatives like the revival of the Freedom Quilting Bee Legacy, a community organization tasked with restoring and reopening a building formerly operated by quilters, would offer welcome employment opportunities as well as a gathering place for creatives (who currently work independently at home) and those who want to take workshops or study with them.

A community meeting at the Gee’s Bend Welcome Center with Souls Grown Deep, Nest, and the Democracy at Work Institute in August 2019. © Scott Browning.

Nobody involved in the initiative expects Gee’s Bend to transform into the kind of hipper-than-thou hotbed that Marfa has become—nor do they want it to. “There won’t be any G6s landing—this is a bus trip,” says Maxwell Anderson, the president of Souls Grown Deep.

But he maintains that the community could conceivably become a regular stop on tours of the American South undertaken by those interested in the history of Civil Rights—especially people drawn to Alabama because of its new Legacy Museum and National Memorial to Peace and Justice.

For her part, Mary Margaret Pettway is already picturing a new future for Gee’s Bend.

In 10 years, “virtually every house would have a marker, and people can go and tap their smartphones and pull up information about that quilter,” she imagines. “It would be something to see. We are living history.”