Up Next

George Rouy Has Landed His First Hauser and Wirth Show at Age 30. What’s Behind His Stratospheric Rise?

The U.K. artist is one of the youngest artists on the mega gallery's roster. He has planted a curveball with his debut show, now on view in London.

Again and again, a group of writhing bodies becomes one indistinguishable mass in a new series of paintings by George Rouy. The blur of disembodied limbs warps and fades, a shapeshifting border between the self and its surroundings that the British artist calls “the bleed.” If your eye is unsure where on the canvas to settle, this is intentional. Rouy has removed any faces that might serve as “an anchor point,” an easy distraction from the composition’s more carnal implications. The cited historical precedent is Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), for how it “captures chaos, all aspects of human nature, a feeling of being stranded,” yet the vibrant palette also hints at the sensual excesses of François Boucher.

Rouy, aged 30, has become a stealth ultra-contemporary star in recent years, with an auction record of £162,540 ($195,619) set at Christie’s London in March 2023. Two paintings sold over the summer at Phillips Hong Kong and Sotheby’s London met or surpassed their high estimates to fetch $48,728 and $61,428 respectively.

Some of Rouy’s earlier canvases filled with contorted faces are reminiscent of Francis Bacon, which makes sense given the “psychological, under the skin” feel of his work, Rouy suggested. His main influences are artists working at the edge of figuration and abstraction, like Cecily Brown, Willem de Kooning, and Gerhard Richter. He is also guided by a kind of synesthesia; he knows a painting is good when he likes its aura.

Last May, Rouy made headlines as the youngest addition to Hauser and Wirth’s roster, represented in collaboration with his longtime gallerist Hannah Barry. His latest works are the subject of his debut solo show with the mega-gallery at their London location. Called “The Bleed, Part I,” (on view through December 21), a “Part II” version follows in L.A. in February, coinciding with Frieze’s fair edition on the West Coast.

George Rouy in his studio, 2024. Photo: Damian Griffiths, courtesy the artist, Hannah Barry Gallery and Hauser & Wirth, © George Rouy.

A Return to Painting

To a large online following of more than 60,000 on Instagram, Rouy projects an artily unrefined glamor, wearing outré outfits with kitsch ties, bleached hair, an eyebrow slit, and the occasional glint of gold grills. In person, he has an easy-going, unrehearsed manner, greeting me in a paint-splattered tracksuit on a recent visit to his studio. For the past few years, Rouy has been working in an ex-warehouse on an industrial estate in the small Kent town of Faversham, 77 kilometers east of London and not far from Sittingbourne, where he was born in 1994. His father, a hairdresser, and his mother, who worked odd jobs, shared “a creative mind and essence” that they passed on to their children. Both George’s younger siblings, Alfie and Elsa, are also artists.

By the time Rouy started art school at Camberwell in the early 2010s, however, he “felt like an ‘in the closet’ painter because it wasn’t very fashionable or cool,” he said. “I fell out of love with it. Everyone was doing installation work or video.” After graduation, Rouy worked at a Christmas decoration factory, cleaning the lights that came back from central London’s main streets each January, repainting them in the midsummer heat, and loading them into vans come fall. In lieu of a studio, he rented a room with a mezzanine so he could work beneath his bed.

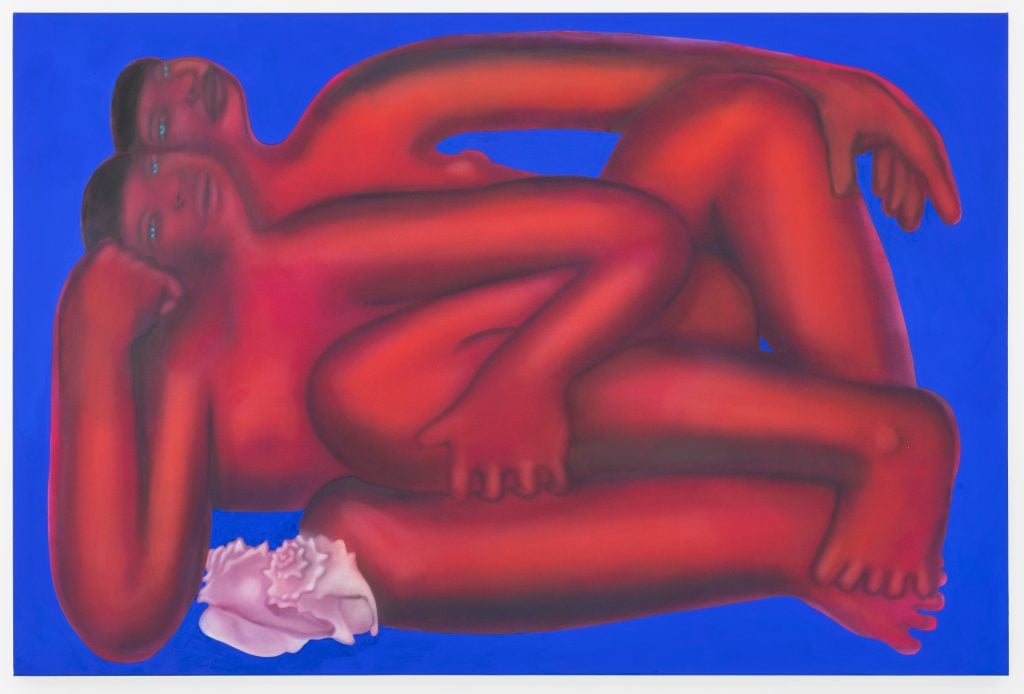

George Rouy, Four Lounging (2018). Photo: © Damian Griffiths, courtesy the artist and Hannah Barry Gallery, London, UK.

The return to painting was fitful. “I started with a stripped-back, very naïve way of doing it,” he said. “I didn’t know what I wanted to paint.” One irresistible lure, however, was that of the human figure. “There are endless ways you can approach it. I love the history of it. What is figurative painting now? How does it reflect on the past?,” asked Rouy. “It’s a nice thing to be part of.”

What began to emerge on canvas were tangles of misshapen limbs with a hefty, almost clumsy quality reminiscent of Picasso’s classical period. These glowing pink or orange bodies with dazed expressions were articulated by hazy outlines that almost thrum on contact with the outside world. It is no surprise that El Greco was an influence. Before long, the works caught the eye of southeast London gallerist Hannah Barry, who gave Rouy his first show in 2018. By the time of his second, “Clot” in 2020, Rouy’s style was undergoing a radical transfiguration.

George Rouy, Clot (2020). Photo: © Damian Griffiths, courtesy the artist and Hannah Barry Gallery, London, UK.

“I spent about two years trying to break my habit of making everything very pristine and think about how marks can say a lot,” he said. He slowly let “breakages and distortion” find their way in, moments of frisson that draw the eye and “help piece together how the viewer reads the work.” The effect was partly achieved through the introduction of oil paint, applied as a top layer over a flat acrylic base and favored for its more gestural malleability.

By 2022, Rouy had also begun collaging found photographic imagery with fragments of his recent paintings on Photoshop, a loose source material that has brought more anatomical accuracy to the work. The final composition, however, is worked out on canvas, as figures are added, then changed or removed. “The painting has its own life, its own history,” said Rouy, pointing out the “scars” on one canvas of a body erased. “You have to try things out, but it’s very clear when a painting feels overworked or hasn’t got that kick. That’s something I always judge a painting on.”

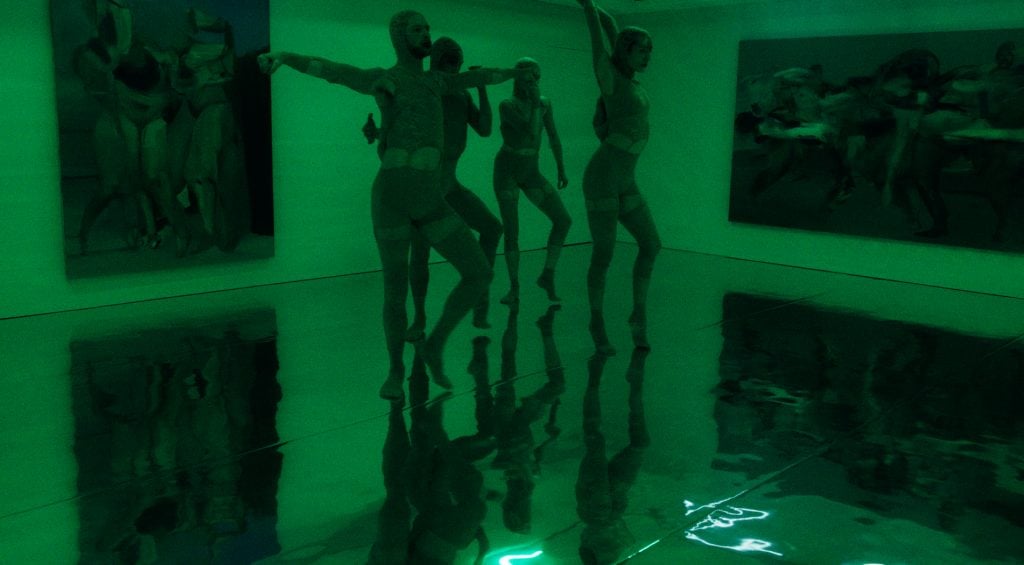

George Rouy and Sharon Eyal, Bodymotion (2023). Photo: Alexander Ingham Brooke, courtesy the artists and Hannah Barry Gallery, London, UK, © George Rouy and Sharon Eyal.

New Forms

The drive to imbue his work with greater sentiment and vigor saw a breakthrough when Rouy met choreographer Sharon Eyal, a cult favorite among artists and luxury brands. Eyal is known for her spare yet demonstrative performances that center the human form. “There is a narrative but it is within an abstract, a void,” Rouy said. “There are no costumes or set. It is just light, music, and bodies. It is so intuitive to feel emotion in that state.” The pair have collaborated on Bodysuit, a performance with music composed by Rouy that debuted at Hannah Barry last year. It will be reprised in London in January, with Rouy producing a new painting in live response to the dancers.

By the time an artist is taken on by a mega-gallery, they have usually settled into a familiar groove. However, Rouy arrived at this point much earlier than most, and his style has changed dramatically over the past decade, making his next move feel unpredictable.

Installation view of George Rouy’s “The Bleed, Part I,” at Hauser & Wirth London, 2024. Photo: Damian Griffiths,

courtesy the artist, Hannah Barry Gallery and Hauser & Wirth, © George Rouy.

Amid the lively scrum of bodies that has become his trademark, hang a few canvases of daring subtlety. In these “phantom paintings,” the figure has almost dissolved into the void entirely, leaving behind only “minimal suggestions” of a hand, a knee, a foot. Drained of color, these monochromatic compositions foreground textural effects achieved by brushing charcoal dust onto a radiant silver ground. “There’s a weightlessness, a powdery quality to it,” said Rouy with excitement, indicating where stray particles had dropped and scattered, shrouding the canvas in a delicate mist. The contrast between illumination and shadow was partly inspired by Chris Ofili’s blue paintings.

Does this invitation to chance over control signal a shift towards abstraction? Rouy believes we can’t help but “read the body within the marks. When we look at the work, we are looking at our own anatomy.” After all, even at their least descriptive, his compositions are a medley of motions made by a body. “I’ve always loved that about painting. It feels so natural to do and it feels so natural to see. To just enjoy human mark-making.”

“I’ve collected a lot of vocabularies, a lot of ways to speak when it comes to figuration,” he added. His sustained experimentation is paying off just in time for his ascendance onto the global stage. “It’s like I’ve been training for a boxing match, and now I’m about to fight.