Art & Exhibitions

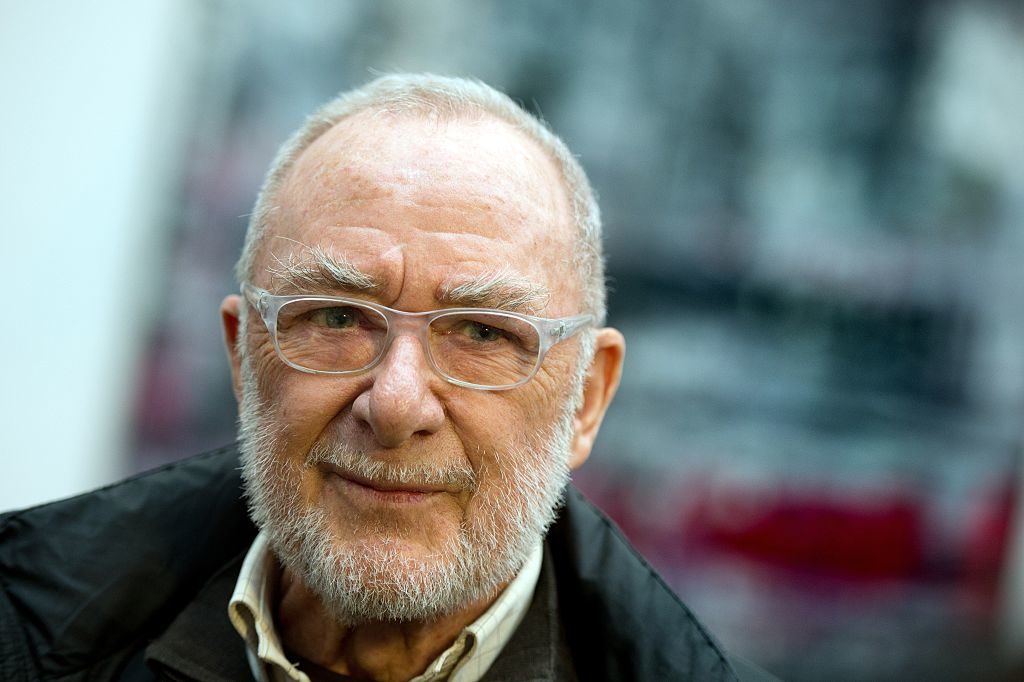

The Experience of Meeting Gerhard Richter: Seismic

We catch up with the legendary artist before his latest show.

We catch up with the legendary artist before his latest show.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

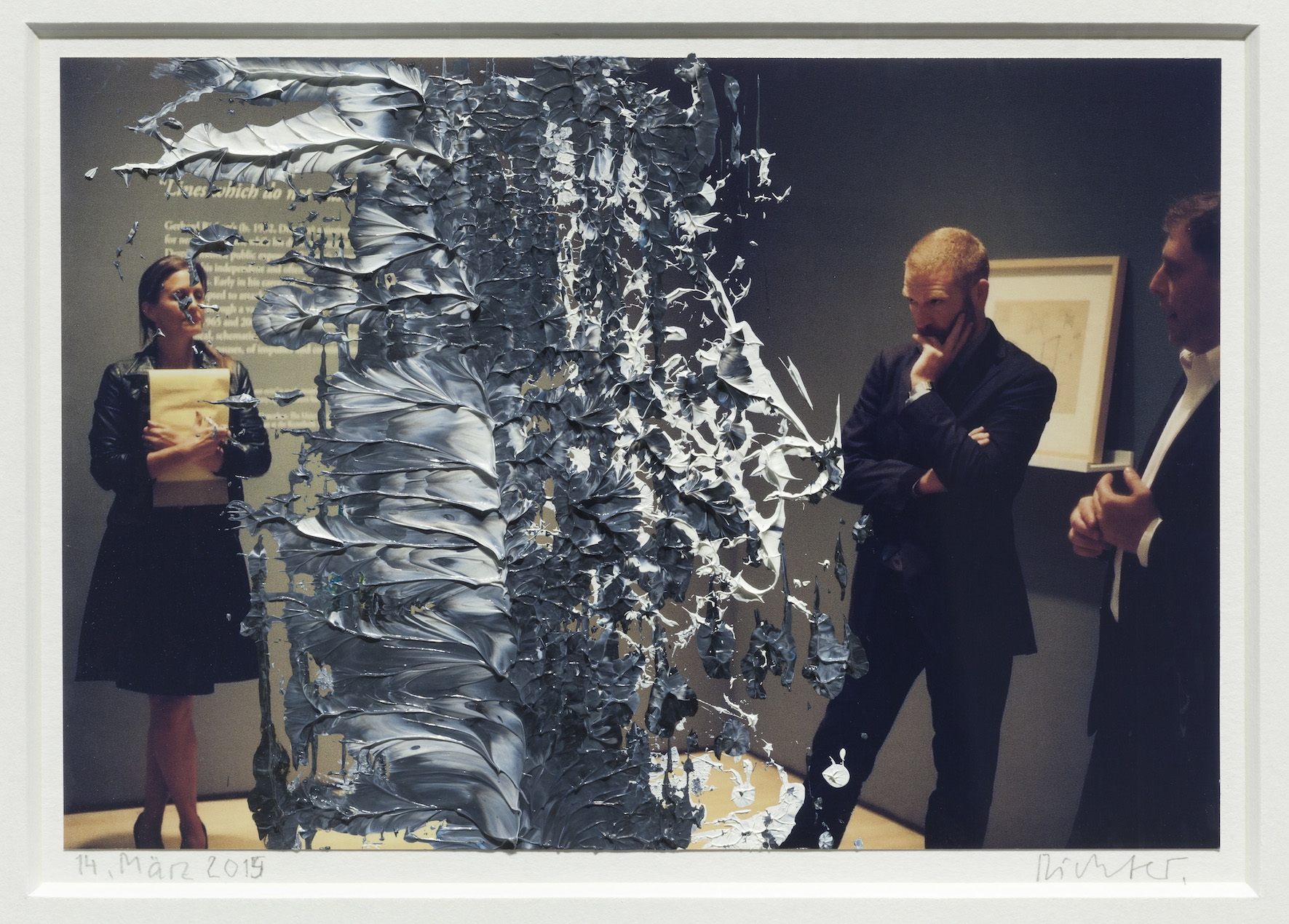

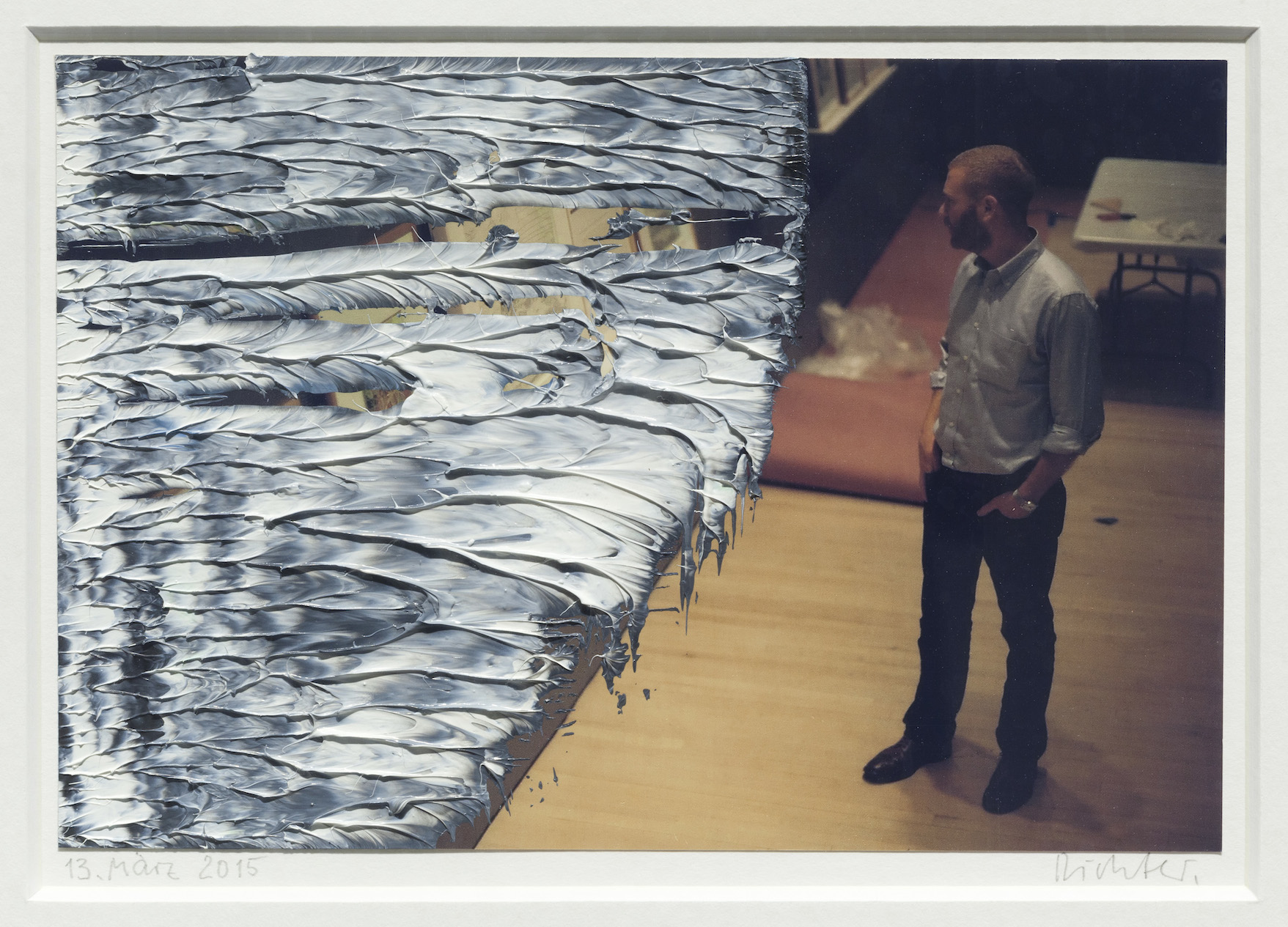

“The problem is now that all of nature, everything, is captured in photographs, so there is nothing to paint. This, for me, puts some fantasy back into it.” These words were uttered recently by Gerhard Richter—the world’s most expensive living painter and our age’s artistic genius, according to a 2013 straw poll Vanity Fair conducted among one hundred of the planet’s “art worthies.” Though knotty, the statement captured the strange magic the artist achieves by dipping select bits of five by six-inch snapshots into mounds of oil paint.

The occasion was a mid-morning viewing of Richter’s latest New York show at the gallery of his longtime dealer, Marian Goodman. A major exhibition of his work is on view there starting Saturday: Twenty oil on canvas paintings, forty pencil on paper drawings, five lacquer on glass pictures, and twelve oil “interventions” on color photographs. Besides constituting a massive honey trap for high rollers—a similarly squeegeed abstract painting to those on view at Goodman sold for $46 million at a Sotheby’s auction in 2015—the new work was also breakfast catnip for a clutch of avid art journalists and a smattering of collectors. The latter arrived incognito for the sort of event that, per Donna Summer lingo, the art world loves to love: a pre-pre-vernissage.

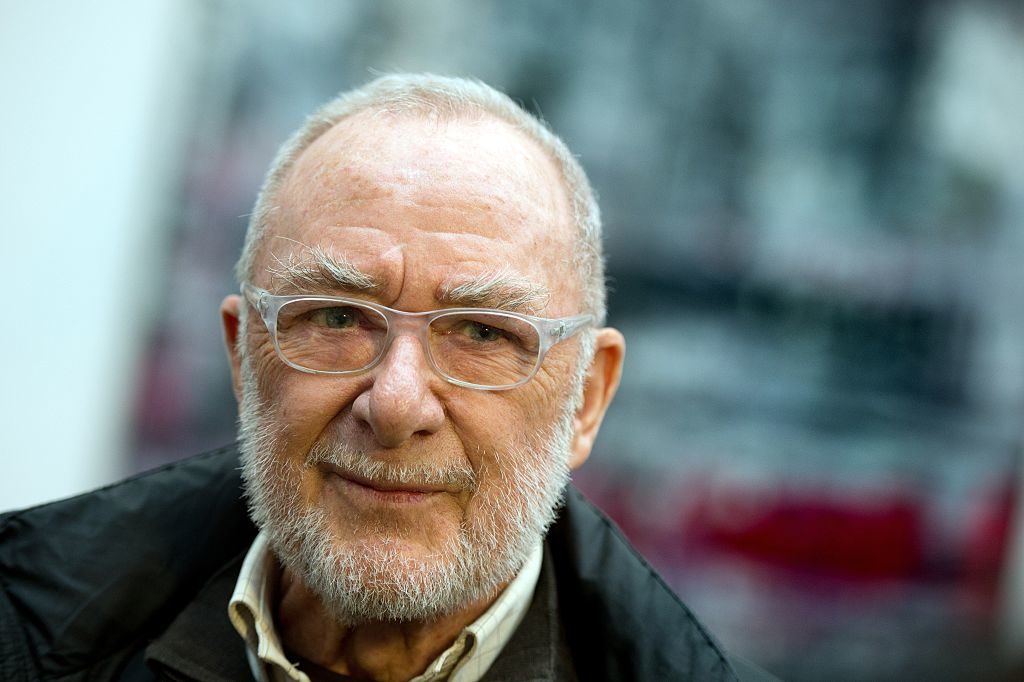

Gerhard Richter, 14. März 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; photographer: Cathy Carver.

One by one, the guests trooped off the gallery elevators to be introduced to the 84-year-old master, dressed informally in a rumpled gray suit, a white shirt, sans tie. Everyone shook his hand, mumbled a few phrases and quickly excused his or herself to carefully scrutinize the art. Since 2011, Richter has been on the record as characterizing American art lovers as “very direct”; ironically, most of the morning’s attendees appeared simply too intimidated to speak to him.

In Gerhard Richter Painting, a documentary about the artist, Richter tells an assistant how a perfect stranger approached him at one New York opening to congratulate him on some paintings, only to dismiss others as “bullshit.”

Gerhard Richter, 940-6 Abstraktes Bild (2015), 940-7 Abstraktes Bild (2015), 940-8 Abstraktes Bild, (2015). Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; photo by Alex Yuzdon.

“What do you say to Picasso?” I asked a colleague who seemed equally perplexed by his encounter with the famous German. A few minutes later, Linda Pellegrini, the gallery’s communications director, requested I approach the great man. Inexplicably, he was alone and fidgeting in the middle of a gallery full of his celebrated paintings. After a second introduction and some small talk, I found myself by the artist’s side in another room as he schooled me on the finer points of a few of his more inscrutable artworks.

“I took all the photos except this one and that one,” he said pointing to a pair of prints that had clearly been taken inside an art gallery. “My friend,” he said, stopping himself before blurting out an actual name, “took those at my exhibition at the Drawing Center, and then mailed them to me; they’re the only ones here that are not of nature.”

Unlike most of the other snapshots of forests and trees with scalloped daubs of multicolored paint, the photo showed three formally dressed art professionals contemplating an object outside the picture’s frame. In the space between, Richter introduced a pillar of oil paint in charcoal and titanium white. Earlier, when showing me the pictures he made by pouring and then moving colored lacquer around glass panes, Richter confessed that the results looked “perhaps too easy.” That might be so, I told him, but this painted photograph did not at all seem “too easy” to me.

Gerhard Richter, 13. März 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; photo by Cathy Carver.

After screwing up the courage, I suggested that the white and gray column might be the ghost of paintings past. A mischievous look came into in his eye; then he laughed out loud. “I’ve been looking for him everywhere,” he said.

A few hours later, a gallerist friend from Copenhagen texted to ask what the experience of meeting the German had been like “on the Richter Scale.” My answer: “Freund, wherever great art appears, the earth moves.”