Reviews

What One Mysterious, Easily Overlooked German Painting Taught Me About How to Visit a Museum in the Age of Blockbusters

Untangling why a little-known painting by Christoph Paudiß feels so prescient today.

Untangling why a little-known painting by Christoph Paudiß feels so prescient today.

Ben Davis

This is an essay on what it means to visit a museum, or, better, what it means to write about visiting a museum.

Recently I was in Vienna to give a talk, and I did what visitors do in Vienna, whether they care for art or not: visit the Kunsthistorisches Museum. It is one of the world’s most celebrated collections of art, a relic of the Hapsburg monarchy’s rapacious splendor, massive and full of numinous paintings presented in a stately manner.

I waited in a long line for a ticket, in a downpour, then climbed the grand staircase and finally arrived at the European painting galleries, with their twilight lighting. I followed the itinerary laid out in the museum brochure, bobbing between the highlights: Bruegel’s earthy, gnomic Tower of Babel; the urbane bombast of Rubens’s The Miracles of Saint Loyola; the trapped-in-amber tranquility of Vermeer’s The Art of Painting.

I try to not only follow the itinerary, however, and at any rate, it was not any of the famous paintings that seized me with the most force. Instead it was a small painting of a weather-beaten old man in a felt cap, hung in Gallery XII, close to the door that takes you to the Vermeer and therefore often passed over on visitors’ way to it.

There is a sort of method I follow when it comes to navigating museums. You can’t see everything and the highlights are usually the highlights for a reason, so you should see them. But I also find that art history is always subtly changing as I change, different parts of it becoming activated or losing force. To pay some attention to this personal dimension—and to avoid the ticking-the-box, photo-opportunity type of visit that contemporary life encourages—it is best to simply wait to see what speaks to me, then to sit down and try to figure out why.

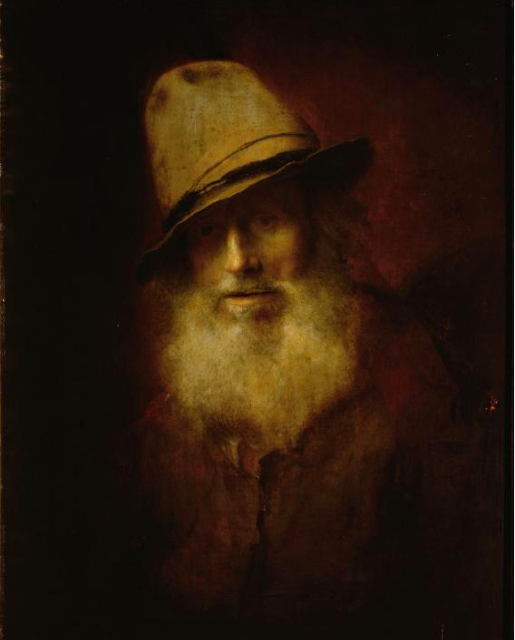

Christoph Paudiß, Ein Marodeur (A Marauder) (1665). Image courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum.

The painting I discovered this time is called Ein Marodeur (A Marauder), dated 1665 (or at least that is the information from its label in the galleries; on the Kunsthistorisches Museum website it is called Bildnis eines bärtigen Mannes mit Hut (Portrait of a bearded man with a hat), and dated 1663).

The man’s face has a slightly unplaceable expression, gazing off to his right. You read it, based on his unruly white beard and rumpled costume, as plaintive.

A particularly unusual aspect of the painting is how dark everything is outside of the face and hat. It is as if a candle has picked him out of the dark. It’s not just that the man is framed against a black background. You can barely make out what is going on with his torso at all, which merges into the darkness.

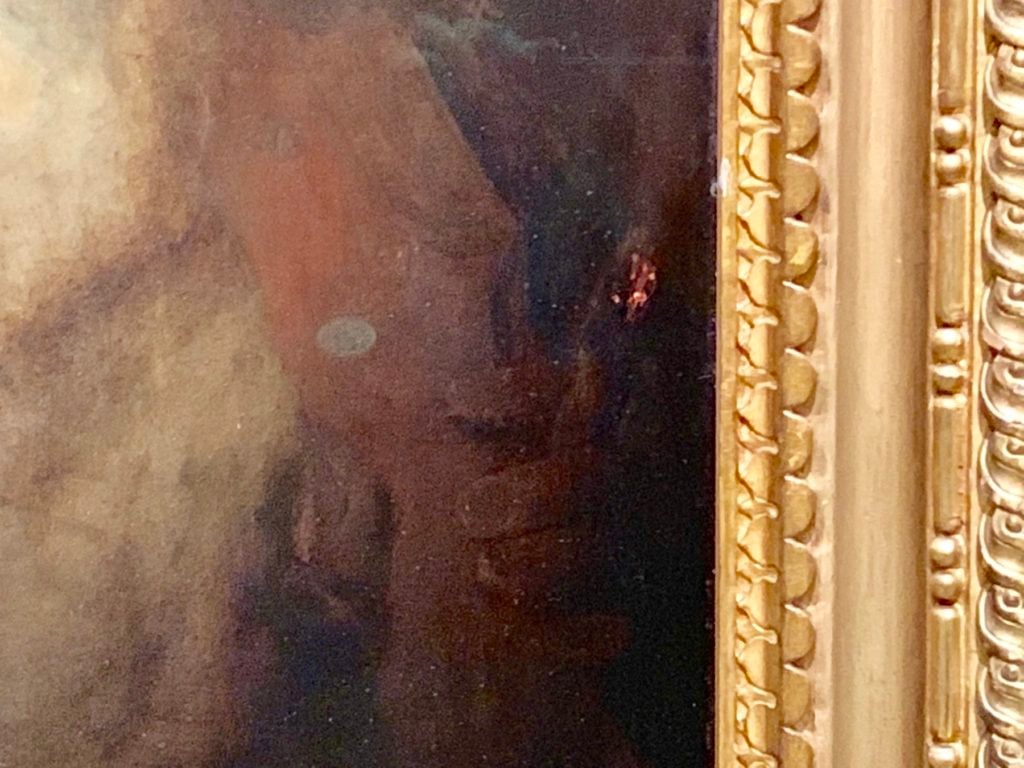

Indeed it took me some minutes to see the most important feature of the painting, the one that makes sense of the title A Marauder: The old man is carrying a rifle, slung over his left shoulder. As I looked closer, I also think I spot that he is holding a cigar gripped between his index and middle finger, a few dashes of paint seeming to suggest embers smoldering in the darkness. But it’s not mentioned anywhere, so maybe that’s in my head.

Detail of the hand in Christoph Paudiß’s Ein Marodeur (A Marauder) (1665). Image: Ben Davis.

At any rate, having picked out these details, the world-weary man now seems to have a bit more of a twinkle in his eye. He appears less supplicant, more challenging. He seems to be sizing up something off to the side.

The artist is Christoph Paudiß, whose dates listed here are 1625 to 1666—a brief life, ending in his early 40s. Little about him is available in English and little, I gather, is known in general, though a show some years ago—the only one dedicated to Paudiß, as far as I can see—styled him the “Bavarian Rembrandt.” He was, in fact, a student of Rembrandt, carrying the Dutchman’s style of poignant chiaroscuro with him back to the German lands.

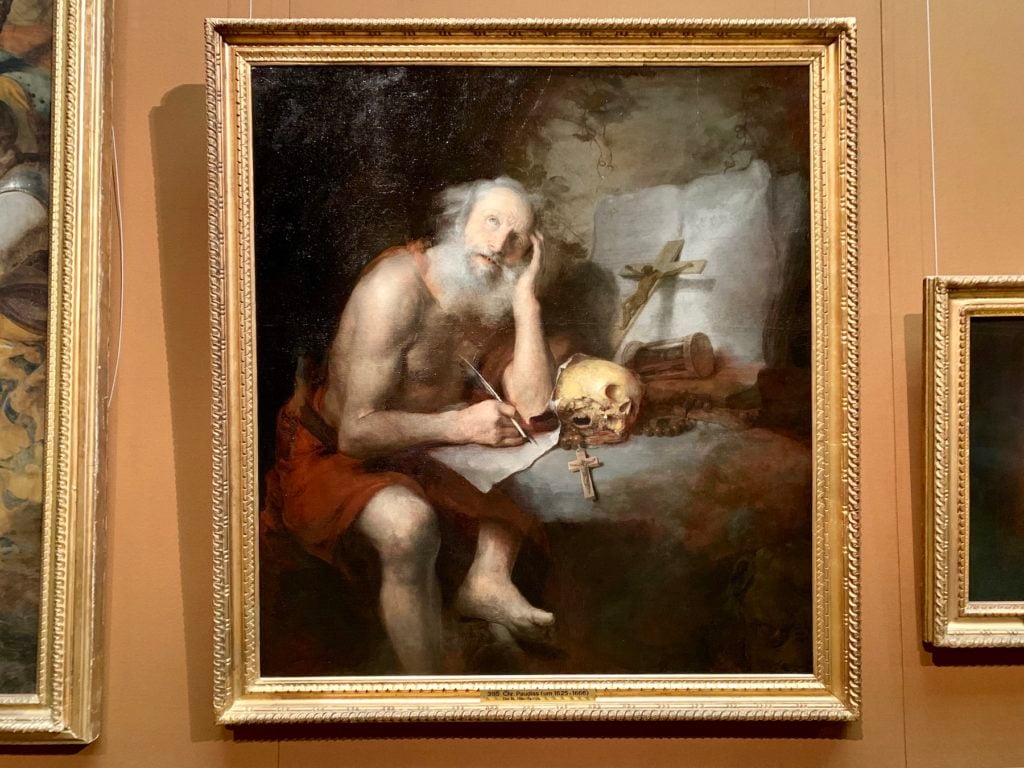

Christoph Paudiß, Hl. Hieronymus (Saint Jerome) (ca. 1656-58). Image: Ben Davis.

A text in the gallery notes that A Marauder sets out “to search for dignity in the lonely old man.” Evidence for this mission sits right next to it at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in another, larger painting, also by Christoph Paudiß: Hl. Hieronymus (Saint Jerome) (ca. 1656-58).

Saint Jerome, much beloved by Paudiß’s countryman Albrecht Dürer 100 years before for his status as a scholar-saint (he was the translator of the Bible), is depicted in his study, staring up, transfixed, with his symbol, the skull, before him. The accent falls on Saint Jerome’s austerity and the solitude wherein he contemplates the fleetingness of earthly things. Most importantly it strikes me—and it’s amazing how long it takes to realize this—that Jerome’s features are the same as those of his neighbor, the outcast marauder.

Left: Detail from Hl. Hieronymus (Saint Jerome). Right: Detail from Ein Marodeur (A Marauder).

The old bandit is spun from the same symbolic stuff as the saint, the two images connected via the idea that poverty symbolizes grace rather than wretchedness. At the same time, the identification of the figure in A Marauder as a bandit means that the holy and the criminal are brought close, complicating its religious sentimentality for me.

Paudiß lived in a world where the sense that the high ideals of civilization could break down, and that anyone could be reduced to the state of violence and desperation, was not at all abstract. His life coincided with the pan-European disaster of the Thirty Years War, a complex, multi-fronted epic of carnage that stemmed from Protestant and Catholic rivalry. Much of German-speaking territory was riven by violence, famine, and plague. Banditry actually was a fact of daily life as the social order broke down.

What Paudiß knew of this, returning from the Netherlands in its aftermath, I do not know. He seems to have lived a restless and wandering life, moving from town to town and job to job for a few years at a time. He is supposed to have died in distress after losing a painting contest. From the evidence of the paintings I know, he had a taste for the eerie, unconventional, disturbed atmosphere that might have fit this wounded historical moment.

A third painting on the same wall with A Marauder at the Kunsthistorisches Museum gives a sense.

Christoph Paudiß, The Martyrdom of Saint Thiemo (1662). Image: Ben Davis.

Titled The Martyrdom of Saint Thiemo, the painting depicts the death of the titular German saint. Aside from the ghastly image of intestines being unrolled on a winch, the painting has a mannerist and irrationalist feeling—the figures all looking in different directions, the composition crowded in parts and empty in others, the setting haunted by fragments and ruins, the rendering of different subjects ghostly to the point of looking incomplete.

There’s a real feeling of modern broken-ness and displacement that shines through. The painting’s symbolically charged and epiphanic moment coincides with a sense of the world as chaos and randomness. Maybe on some level that aura also seeps its way into the unsettled mystery of the later A Marauder.

But The Martyrdom of Saint Thiemo stands out, even today, as a gory, horror-show spectacle. As for the much smaller painting, my guess is that not one in a thousand visitors to the Kunsthistorisches Museum will stop to give it the seconds you need to make out what the old man is doing. Those who do and want to know more will find very little information about the painting or the artist easily available.

The old man sits there, in the shadows, just half seen.

Installation view of Gallery XII. Image: Ben Davis.

The painting moves me. As I turn the picture over in my head in retrospect, I realize that the reason why is that its subject and atmosphere seem to reach forward in time to stand as an allegory for its contemporary fate.

For art history, this painting is present—but it is neither famous nor a novelty, the two conditions to command contemporary attention. There’s no news hook to hang this article on. The velocity of modern media and pressures of modern life press against me ever having the time needed really to know it. The tenuous light that picks out the old man represents the narrow, fleeting window of attention that connects the painting’s world to mine.

When I do stop to look, a story emerges, or at least the sense of one. Maybe the man is a wily bandit who’s lurking in the darkness; maybe he’s a poor man who is hunting or standing watch over his meager possessions or who has had to defend himself. And so, the painting also reads to me as being about all that’s hidden in plain sight that can still threaten or surprise, the things secreted in art that the catastrophes of time and forgetting haven’t quite managed to take away.

When you think about it, A Marauder stands for the best-case fate for the typical piece of art in a museum—which then also makes it stand for the typical condition of “Art” when you strip away the myth of its transparent timelessness. That fate is not to vanish. It endures. But it’s also not to inspire lasting ecstasies of interpretation or to summon crowds. Instead, it is to be present but not present, lurking in the shadows, waiting for the moment when it might actually be seen and known.