Art World

A New Book Collects the Best Recreated Artworks From the #GettyChallenge—and Reflects On Why the Project Resonated So Much

The public’s understanding of art history was surprisingly sophisticated, it turns out.

The public’s understanding of art history was surprisingly sophisticated, it turns out.

Taylor Dafoe

This spring, as people around the world were acclimating to life in lockdown, the Getty Museum asked its social media followers to participate in a challenge. The rules were simple: recreate your favorite work of art with three items in your home and post an image of it online.

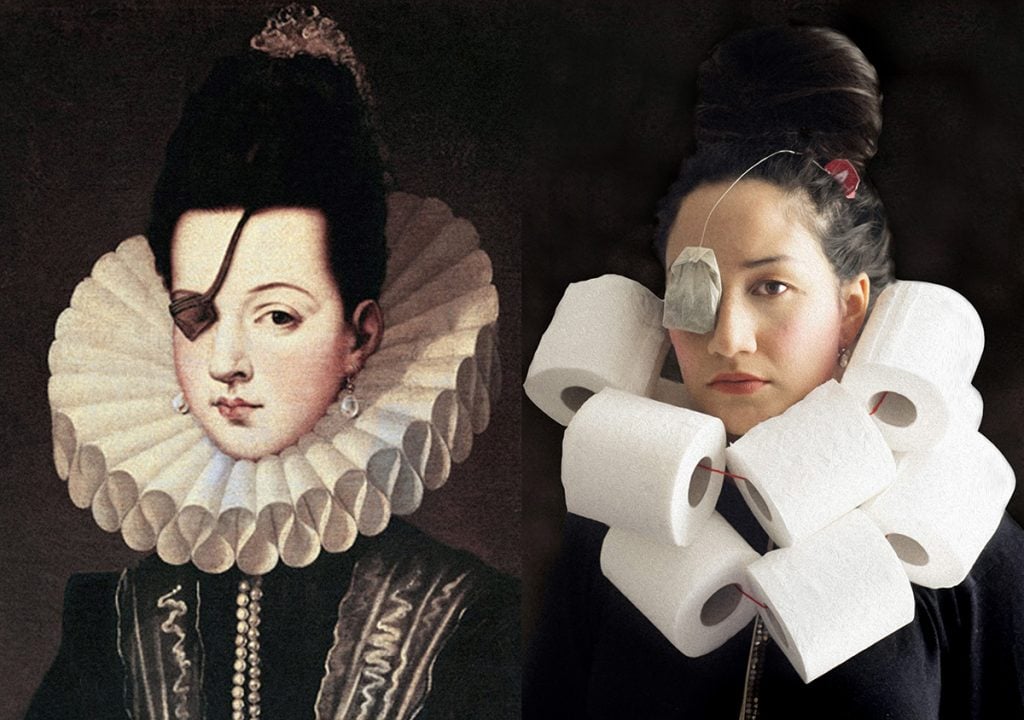

You undoubtedly saw examples: bored quarantiners plotted out starry nights in dried pasta and aped the august ruffs of Old Master subjects using toilet paper rolls; they dressed their dogs up as pearl-earring’d girls and penciled in unibrows for Frida Kahlo selfies.

The project was a rare example of visual art crossing over into the broad cultural consciousness on a massive scale. And what’s more, it managed to do so in a way that felt demonstrably inclusive, communal, and educational—adjectives that appear in just about every museum’s mission statement.

But why did this particular social media gimmick—which certainly wasn’t the only one of its kind—so resonate with quarantiners?

Édouard Manet, Jeanne (Spring) (1881). Re-creation: Jeannette Hulick.

A new book collecting hundreds of submissions to the #GettyChallenge may offer some answers.

Off The Walls, as the book’s titled, doesn’t purport to explain the fervor the project inspired. But it does lay bare the results in a single place. And now that some time has passed since these playful recreations dominated our feeds, we can look at them more objectively and make some informed guesses.

“I think there’s something deep that it tapped into around coping with this worldwide trauma that we were going through,” says the Getty’s assistant director of digital content Annelisa Stephan—one of two people primarily behind the initiative. “It felt healing for some people and it felt healing, looking from the outside, just to see how positive people—total strangers—were about one another’s work. It struck a note of positivity that I think was nourishing against a backdrop of COVID and the political situation.”

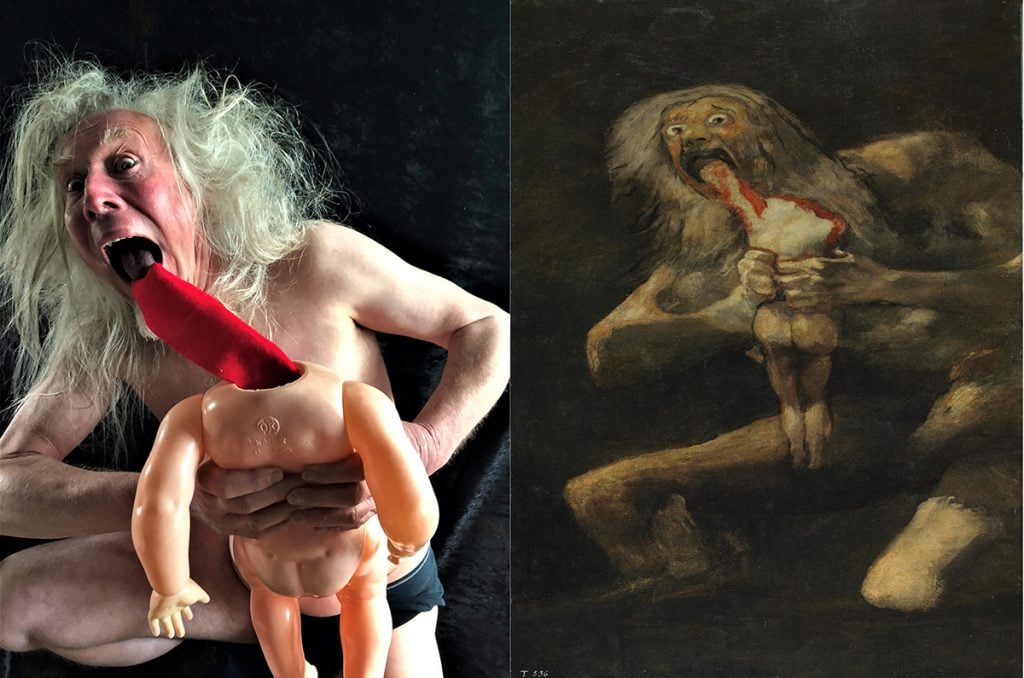

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Saturn Devouring His Son (ca. 1820–23). Re-creation: Mark Butterfield. Photography by Cleo Butterfield.

Inspired by @tussenkunstenquarantaine, a Netherlands-based Instagram account credited as the first to come up with the art recreation quarantine challenge, the Getty launched its own campaign on March 25. Hard numbers are hard to quantify given the way the challenge metastasized over the internet, but Stephan estimates that more than 100,000 people worldwide submitted their own photos. In terms of likes, shares, and forms of more passive engagement, she says it easily reached tens of millions. The goal for a normal museum campaign like this? About 25 or 30 participants.

“We had no idea in a million years that it would strike such a chord,” Stephan says.

Alonso Sánchez Coello, Ana de Mendoza de la Cerda, Princess of Éboli (16th century). Re-creation: Laura Belconde.

Individual images, too, and the thematic connections they shared with other recreation efforts, might clue us in to the psychosocial dynamics that turned the simple social media challenge into a global phenomenon, Stephan explains. Toilet paper was everywhere, of course, as were cans of food—obvious souvenirs of stay-at-home life. But what else? What about the artworks being referenced? Were they famous paintings of pestilence and war or pastoral scenes of quant escapism?

The public understanding of art history was surprisingly sophisticated, it turns out. Portraits by Dutch masters Rembrandt and Van Eyck, both of whom used mirrors (in the frame and, likely, outside it) to paint their complex compositions, were popular, suggesting that recreators were hip to the perspectival layers involved in taking and sharing a selfie. Surrealism was also big, as quarantiners frequently drew on Dalí, Magritte, and de Chirico for inspiration—which makes sense, given the bizarreness of the moment.

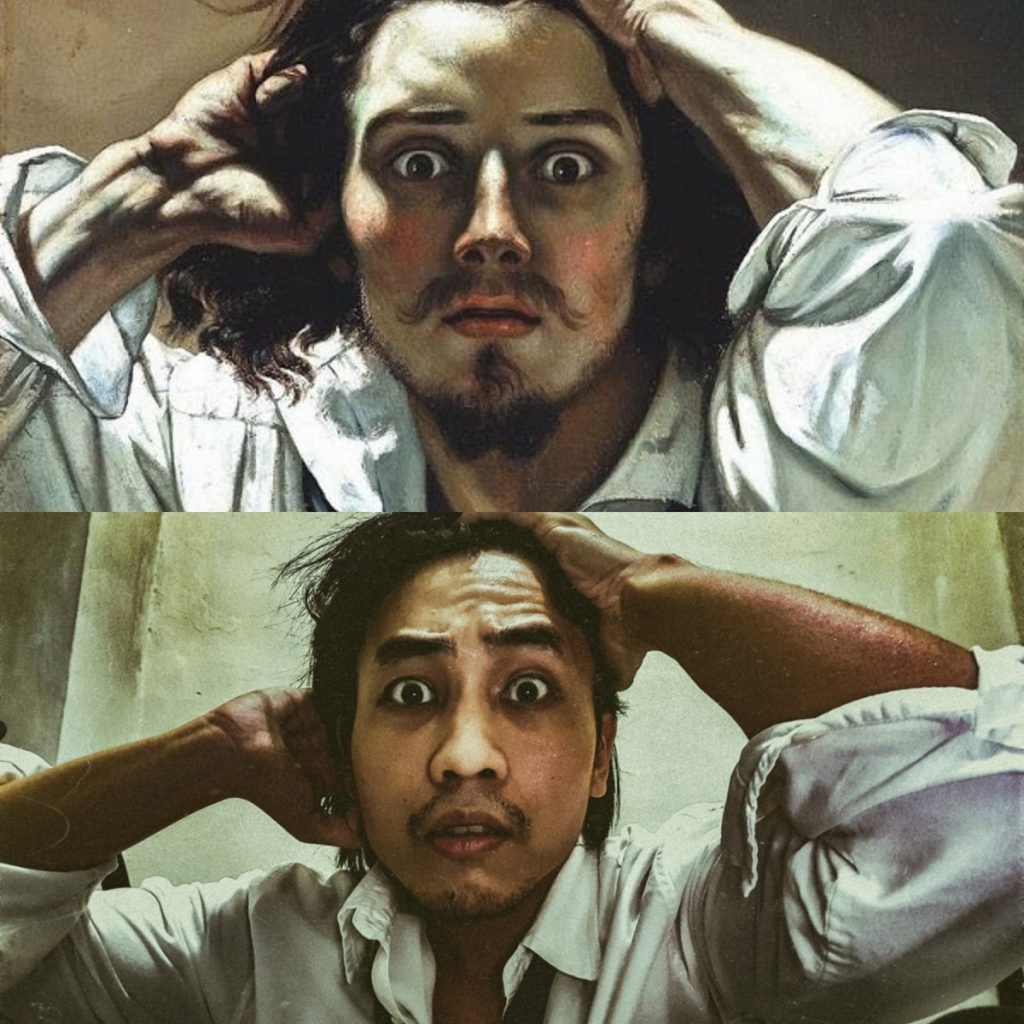

Gustave Courbet, The Desperate Man (Self-Portrait) (1843–45). Re-creation: Peter Adam Rebadomia.

Other examples were more literal, but no less adept: Gustave Courbet’s The Desperate Man (Self-Portrait) made several appearances, as did Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Munch’s The Scream was a prominent choice, but who among us didn’t feel tapped into that expressionistic anxiety this spring?

Off the Walls: Inspired Re-Creations of Iconic Artworks will be out in the US this September. All proceeds from the book will be donated to Artist Relief, an emergency initiative offering resources to artists across the United States.