Art & Tech

An AI Algorithm Developed at MIT Can Spot Similarities Between Artworks Made in Vastly Different Periods of Art History

The MosAIc algorithm compares artworks from the collections of the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The MosAIc algorithm compares artworks from the collections of the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sarah Cascone

Has MIT created the world’s first AI curator?

A new algorithm dubbed MosAIc, developed by MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, alongside Microsoft, uses artificial intelligence to spot similarities between works of art in different media and from different cultural origins, identifying visual connections across history.

Some of the pairings generated by MosAIc, which relies on machine learning and an image-retrieval system, include a drawing of a blue crane by 18th-century Dutch explorer Robert Jacob Gordon, with a delicate piece of blue Persian glassware (a sprinkler with a long, thin neck). Though the match seem unlikely, there’s something undeniably uncanny about the visual relationship between the two.

“Every time I use the algorithm, I find surprises,” PhD student Mark Hamilton, who has published a paper on his work with MosAIc, told Artnet News in an email.

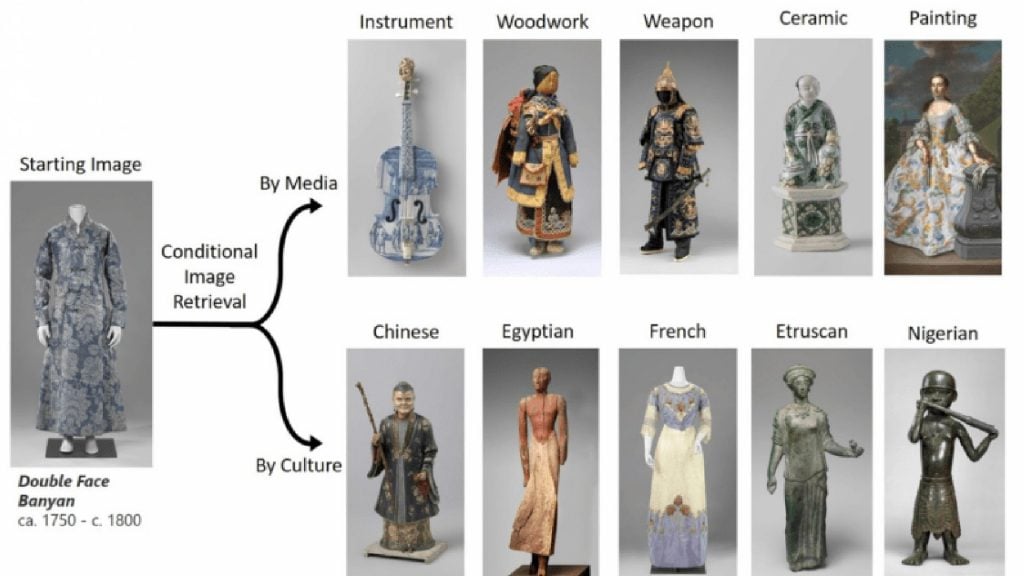

He was shocked for instance, when he asked MosAIc to find a musical instrument to compare to a 18th-century banyan, a Dutch garment inspired by Japanese kimonos.

MosAIc matches a Dutch garment with a musical instrument. Courtesy of MIT CSAIL.

The system proposed a Delft violin that shares the fabric’s blue and white coloring, “but also hints at a more fundamental connection between these two works,” Hamilton said. “More specifically, these works are evidence of the shared influence of Dutch-Chinese porcelain trade in the 16th to 18th centuries. This trade pipeline ignited Europe’s love of blue and white and cobalt-blue glazed porcelain from Jingdezhen.”

For the project, researchers trained the AI using image sets from the open-access collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in the hopes of identifying overlooked connections and provide new insights into relationships in the visual world, reports MIT.

“We hope this approach can be used as a tool to help art historians find new patterns in history and gather evidence to support their hypotheses,” said Hamilton.

Typical image-retrieval systems work within set collections of already-grouped images, pairing similar images from the same artist or brand. MosAIc was designed to look beyond color and style to also consider works’ meanings and themes.

MosAIc presents various possible pairings for a Dutch garment. Courtesy of MIT CSAIL.

The works from the Met and Rijksmuseum collections were organized using a “conditional KNN tree,” a treelike structure where “branches” can represent different artists, media, or cultures.

The image-retrieval system starts at the tree’s “trunk” and searches through each “branch” for the best match to the queried image.

MosAIc differs from existing projects, like Google’s “X Degrees of Separation,” which aim to identify connections between two chosen images, in that the user inputs just one artwork, and the AI finds an array of possible matches.

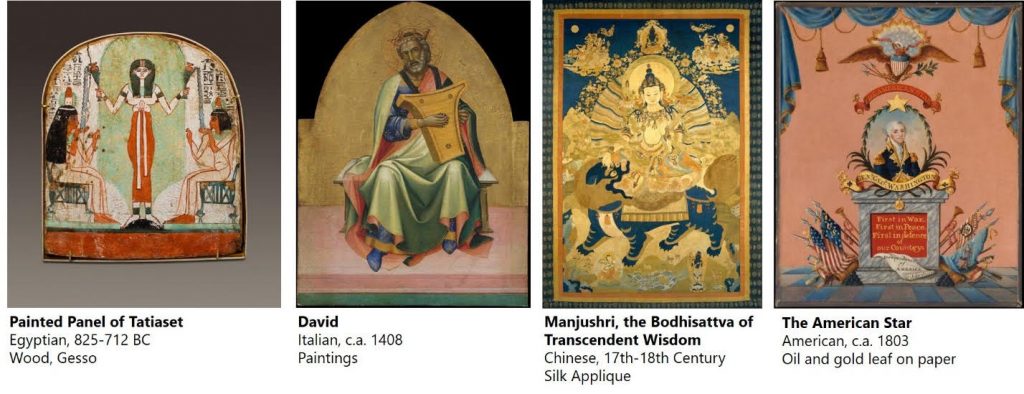

MosAIc presents various possible pairings for an ancient Egyptian painting. Courtesy of MIT CSAIL.

Hamilton and his team were also intrigued that MosAIc also showed an ability to identify the generative adversarial networks (or GANs) used to generate deepfakes. The program was able to pick out errors in datasets that might otherwise fool the human eye.

The project was inspired by the recent Rijksmuseum exhibition, “Rembrandt and Velazquez,” which explored the similarities between the Dutch and Spanish masters of the 17th century—such as their nearly identical color palettes and shared mastery of light and dark—despite the fact that they almost certainly never met, or even knew of each other’s existence.

Hamilton was particularly struck by the unexpected similarity in the exhibition’s pairing of Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion and Dutch Golden Age painter Jan Asselijn’s The Threatened Swan.

In “Rembrandt and Velazquez” at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, curators presented the unlikely but similar pairing of Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion (left) and Jan Asselijn’s The Threatened Swan. Courtesy of MIT CSAIL.

It’s the kind of pairing that MosAIc might make—but Hamilton isn’t aiming to render curators obsolete.

“This software could help curate an exhibition, but it’s not aiming to replace curators,” he promised. “We have used this approach to find incredibly interesting and thought-provoking pairs of images. However, art historians and curators can provide a much deeper understanding and historical context of these matches.”

“Our method is good at building a particular type of exhibition: unlikely pairs of art that span barriers and share common structure,” Hamilton added. “The world’s art exhibits are infinitely varied, each with their own thesis, and this is what makes art wonderful. We hope the community can see this method as adding a distinct voice to the chorus, not replacing it.”