On View

Ghana’s Buzzed-About Venice Biennale Pavilion Is a Clear First Step in the Country’s Bid to Become a Global Art Destination

The knockout pavilion, which includes work by John Akomfrah and Ibrahim Mahama, appears to be part of a bigger plan.

The knockout pavilion, which includes work by John Akomfrah and Ibrahim Mahama, appears to be part of a bigger plan.

Julia Halperin

Throughout the Arsenale, the medieval dockyard complex that houses a number of national pavilions for the Venice Biennale, a common refrain can be heard echoing through the corridors: Which way to the Ghana Pavilion?

The West African country has made a splashy debut in the international art exhibition, which opened for previews yesterday. Its pavilion—a series of curved, interlocking chambers designed by architect David Adjaye—houses an all-star lineup, including new works by sculptor El Anatsui, video artist John Akomfrah, and painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Nearly all of the art was commissioned especially for the occasion.

The installation by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in the Ghana Pavillion at the Arsenale during the 58th International Art Biennale on May 07, 2019 in Venice, Italy. (Photo by Luca Zanon/Awakening/Getty Images)

All this flash is by design. At the inauguration yesterday—which was attended by Ghana’s First Lady, Rebecca Akufo-Addo—officials were unusually direct about their objective for the project: to enhance Ghana’s position on the global stage and to increase tourism. This is art as a tool for soft power—a diplomatic tactic that many countries across the globe have stepped away from as governments continue to slash arts funding.

Ghana, however, is moving in the opposite direction. And it is well positioned to capitalize on the international growth of interest in art of the African diaspora. The budget for the country’s ministry of tourism, culture, and creative arts rose 120 percent between 2014 and 2018, from just $6.5 million to $14.5 million, according to published government estimates. The latter figure is expected to more than triple by 2022, the documents state.

The Venice Biennale project—designed to present Ghana as the “preferred tourist destination in sub-Saharan Africa,” the country’s tourism minister, Barbara Oteng Gyasi, said at the launch—is a part of this grand plan.

The pavilion’s debut also coincides with the so-called “Year of Return,” a major national marketing campaign launched to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans to the United States. “We welcome our brothers and sisters of the diaspora home,” Gyasi said in Venice, encouraging all who were gathered there to visit Ghana.

The pavilion itself echoes the notion that those in the Ghanaian diaspora are an important part of the country’s story. Of the six artists in the exhibition, only three currently live in the country; one, Yiadom-Boakye, was born in the UK.

Installation view of El Anatsui in the Ghana Pavilion at the 58th Biennale di Venezia. Photo: David Levene.

Both the curator of the pavilion, Nana Oforiatta Ayim, and the architect, Adjaye, have been working with the government for years on various other arts initiatives, including the construction of a new cathedral in Accra and the transformation of a 17th-century castle into a museum. An ultramodern, 240-acre cultural village is also underway in the capital. The Venice exhibition will also travel to Accra after the biennale closes.

The stakes are high. Although Cape Town and Marrakech currently boast more developed arts infrastructure than Accra, no city in Africa has emerged—as Hong Kong has in Asia—as the continent’s clear art-market hub and international meeting place. And Ghana’s economy has been looking up since the discovery of offshore oil deposits in 1992. This year, the International Monetary Fund projected its economy would grow 8.8 percent, making it the fastest-growing in the entire world.

Still, no country can become a cultural destination without good art and artists. But the Venice presentation makes clear that Ghana has those in spades.

One could spend hours in the pavilion, whose sand-colored walls are made with soil imported from Ghana. Each of the six artists chosen by Oforiatta Ayim (with input from legendary curator Okwui Enwezor, who served as an advisor on the project until his death in March) has an older or younger counterpart in the show—a canny way to illustrate how Ghanaian artists of different generations are using similar media and genres to quite distinct effects.

The pavilion is framed by two artists who use found and cast-off objects as raw material: El Anatsui and Ibrahim Mahama. The former, a grand figure in the African art world, has created three new tapestries from his trademark smashed bottle caps. The largest, a wall-engulfing yellow work, references the damage gold panning has wrought on Ghana’s rivers.

A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History by Ibrahim Mahama at the Ghana Pavilion. (Photo: TIZIANA FABI/AFP/Getty Images)

Mahama, meanwhile, has created a bunker-like space constructed out of the mesh used to smoke fish—a reference to another water-based industry that has been transformed with the introduction of new technologies, which now threaten to damage the river ecosystem. The mesh cages are filled with maps, exercise books, and even bits of dried fish, creating what Oforiatta Ayim describes as “a visceral archive of the country.” (Believe it or not, the fish smell is evocative and not at all overwhelming—a true artistic feat.)

Installation view of John Akomfrah in the Ghana Pavilion at the 58th Biennale di Venezia.Photo: David Levene.

The exhibition also presents two artists who work with video: John Akomfrah, a decorated London-based artist with multiple international exhibitions under his belt, and Selasi Awusi Sosu, an artist who has never had a major international exhibition.

Akomfrah’s epic three-channel video, Four Nocturnes, and Sosu’s video installation both seek to create a portrait of lost history through fragments. Akomfrah’s work juxtaposes various episodes of violence in West Africa, from the German genocide of the Herero people to the mass slaughter of elephants, while Sosu traces the construction, investment in, and ultimate abandonment of glass factories after Ghana’s independence.

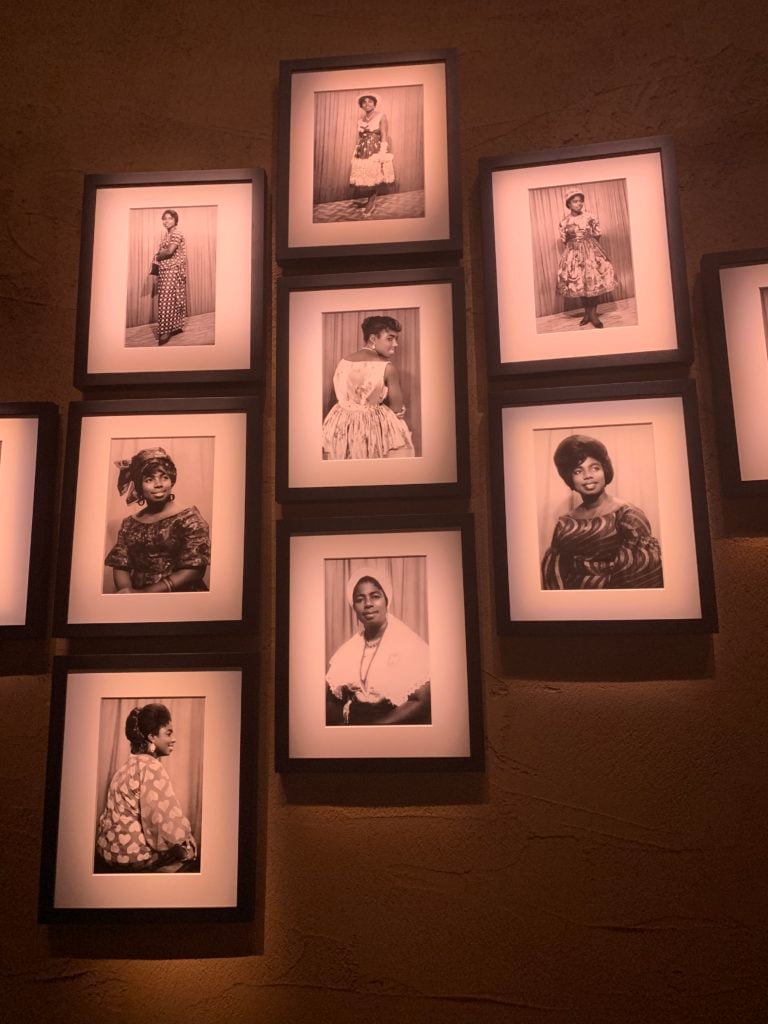

Felicia Abban’s self-portraits at Ghana’s pavilion. Photo: Julia Halperin.

The final duo, painter Yiadom-Boakye and Felicia Abban, considered Ghana’s first female professional photographer, is perhaps the richest pairing. Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits of imaginary figures—including one jubilantly opening the door in front of a wall of peacock feathers and another running elegantly through space—are one testament to the power of imagination to invent the self; Abban’s photographs are another.

Abban was the personal photographer of the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, but also maintained a robust studio practice. She particularly liked taking self-portraits and photographs of other women in a wide variety of attire. Abban offers an energizing new narrative for West African studio photography (which has long been dominated by men like Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, and Samuel Fosso), illustrating that art can be an effective way to present oneself to the world—which is a point that the nation of Ghana seems to be emphasizing on the whole.