Art History

Has a Painting by an Elusive Renaissance Master Been Hiding in Plain Sight?

New research attributes a work in Germany's Alte Pinakothek to Giorgione.

New research attributes a work in Germany's Alte Pinakothek to Giorgione.

Richard Whiddington

To plan or to improvise? This was, in broad strokes, a vital question facing 16th-century Italian painters. Florentine artists favored careful design, a process that began with disegno, drawing. Their Venetian counterparts, by contrast, largely focused on colorito, coloring, often composing directly onto canvas with layered brushstrokes.

In time, Giorgione would prove one of the originators of High Renaissance Venetian art, but a painting that has recently been attributed to the artist evidences him “freely alternating between a draughtsmanly and painterly approach.” So write a group of German art historians about a double portrait that belongs to the Bavarian State Painting Collections in Munich.

Giorgione, Portrait of Giovanni Borgherini and Trifone Gabriele (1509–10). Photo: Sibylle Forster, courtesy Bavarian State Painting Collections.

The painting has been hanging in the city’s Alte Pinakothek since 2011 and though it was recorded in 1745 as being by Giorgione, the work is unsigned and without supporting documents. It’s an ambiguity common to Giorgione (full name: Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco) and together with the fact he died aged 30 makes him an elusive figure, even if his impact is unquestioned. The article published in Art Matters on December 18, however, seems to settle the matter for the work that appears to have left Florence and crossed the Alps in the last decade of the 16th-century.

The painting shows a pupil looking at a teacher who in turn gazes over-the-shoulder at the viewer. It’s a pose and treatment of education that Leonardo da Vinci popularized, which is why the painting was attributed to him when an inventory of Munich’s royal palace was taken in the 1640s. The authors use the writing of the great Renaissance chronicler Giorgio Vasari to show that, in fact, Giorgione was simply adopting Leonardo’s idea.

Attributed to Giorgione, Giovanni Borgherini and His Tutor (ca. 15th–16th century). Photo: Heritage Art / Heritage Images via Getty Images.

In the second edition of his volume The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1568), Vasari mentions encountering a portrait of a young Giovanni Borgherini, the son of a wealthy baker, along with his teacher from Venice in a Florentine palazzo. This was long assumed to be with a painting in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, U.S. There are problems with this attribution, however, the authors wrote. First, the work’s provenance cannot be traced beyond the 20th century. Second, scholars have been unable to connect the painted Borgherini with the historical figure.

By contrast, Giovanni Borgherini is recorded as being the student of the 16th-century Venetian polymath Trifone Gabriele and there’s a portrait medal of the man by Danese Cattaneo that matches the image in the painting. The student is holding an astrolabe, a tool which helps calculate the position of the sun and the stars, a subject for which Gabriele was extremely well-known. Extra proof? “Other visual sources note [Gabriele] was largely bald in his younger years by the age of 40,” the authors wrote. Gabriele would have been 40-years-old in 1510, the presumed date of the painting.

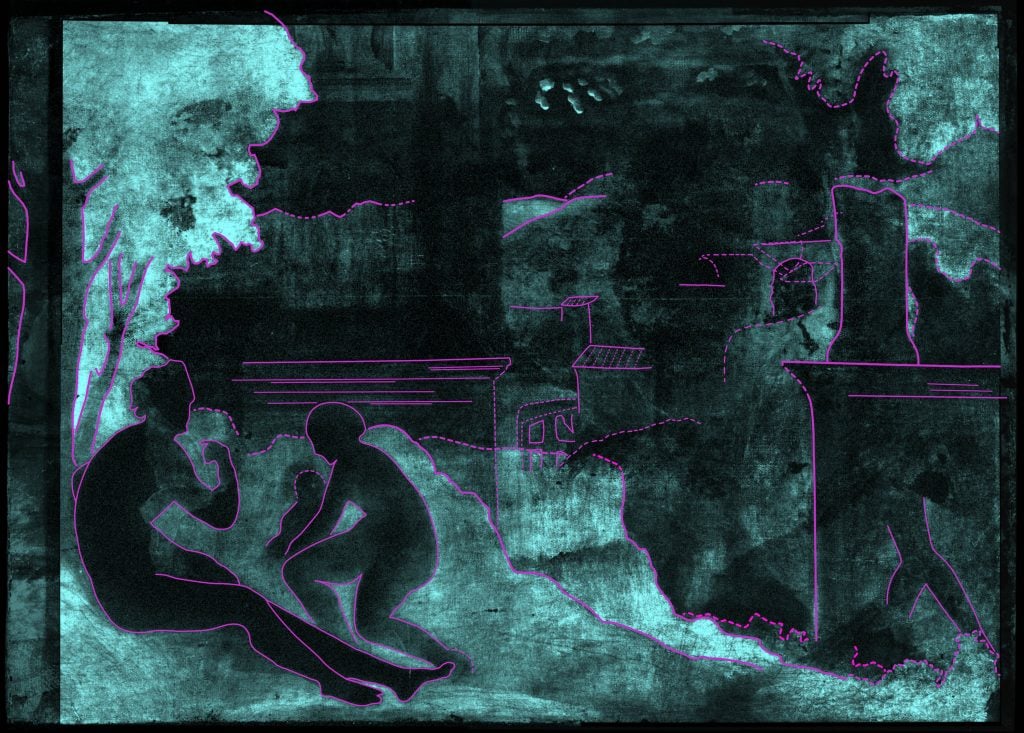

X-ray image of Giorgione’s Portrait of Giovanni Borgherini and Trifone Gabriele (1509-10). Photo: © Sibylle Forster / Anneliese Földes (BStGS/Doerner Institut).

Adding to the painting’s intrigue are the layers beneath the current portrait. A macro X-ray fluorescence scanning has revealed three hidden compositions. The bottom layer, labelled Christ Among the Doctors, is typical of period Venetian devotional painting, the authors wrotte, and has qualities of Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo that Giorgione would have been aware of.

The second layer presents an Arcadian landscape that is very similar in composition to Giorgione’s Tempesta (1506 to 1508). The third layer shows a single figure with a carefully designed Islamic sleeve, one with a “remarkable sensitivity to the materiality and texture of fabrics,” that characterizes Giorgione’s work, the authors said.

X-ray fluorescence scan taken from the back of the painting showing Arcadian landscape. Photo: courtesy Anneliese Földes/Jens Wagner/Doerner Institute.

Giorgione, The Tempest (1505). Photo: Universal History Archive via Getty Images.

Put into context, fewer than 10 paintings have been firmly attributed to Giorgione. The Alte Pinakothek may well have one, which is why Markus Blume, Bavaria’s Minister of Art, has called the discovery “a true Christmas miracle.”