Art World

How Leonardo da Vinci Won the Commission for the Largest Horse Monument of the Modern Era—and Then Lost It

This excerpt from Frank Zöllner's new book on Leonardo details the artist's long struggle with the grandiose Sforza monument.

This excerpt from Frank Zöllner's new book on Leonardo details the artist's long struggle with the grandiose Sforza monument.

Frank Zöllner

Precisely what professional activities Leonardo pursued in the mid to late 1480s in Milan, and how he kept his head financially above water, are questions that remain largely unexplained to this day. All we know for certain about this period is that it saw him designing war machines, some of them more fantastical than practical.

He also drew weapons of all different kinds, fortifications, complex defense systems, siege equipment, and more. Among the curiosities of this phase are heavily armored vehicles, whose immense weight would have all but prevented them from moving. Other ideas seem more immediately dangerous, such as his suggestion that the firepower of smaller cannon could be increased by using what was effectively grapeshot and an automated loading system. Positively gruesome are the horse-drawn chariots armored with scythes, with which the enemy could literally be mowed down. Leonardo copied at least one device of this kind from a contemporary military treatise, Roberto Valturio’s De re militari of 1472, and drew it several times. Not without irony, however, did he accompany his drawing with a warning that this kind of equipment could do just as much damage to one’s own troops as to those of the enemy.

Leonardo did not restrict his skills as a draughtsman to war machines alone. During this same period he was also trying his hand at architecture, producing designs for churches and endeavoring to impress the authorities in charge of the construction of Milan Cathedral with his designs. There are even records of a number of payments made to the Florentine artist from July 1487 onwards in connection with the building of a model for the crossing-dome (tiburio) of the still unfinished cathedral.

Leonardo’s proposals drew little response, however; the contracts went to local Lombard architects who were either better qualified or better connected. More important, in terms of architectural history, are Leonardo’s numerous designs for centrally planned buildings—even if none of them, it seems, got further than the drawing-board. They nevertheless reflect the architectural debate surrounding churches on centralized plans, which was current in the late 15th century and which would culminate, just a few years later, in the proposed new designs for St. Peter’s in Rome.

Only towards the end of the 1480s does Leonardo seem to have returned more productively to the visual arts. The Litta Madonna, a small-format representation of the Virgin and Child, may have been executed at this time or a little later, although its attribution to Leonardo, always contentious, can no longer be upheld. The overall hardness of the contours of the Virgin and Child, and the comparatively mundane atmosphere of the background, point instead to one of Leonardo’s pupils, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, to whom the master entrusted either the entire execution of the painting, or at least its completion. Two drawings from Boltraffio’s hand serve to confirm this suspicion. Leonardo was nevertheless directly involved in the original design of the Litta Madonna, as evidenced by two authenticated preparatory studies.

Study of the Head of a Woman (c.1490). Photo: Musée du Louvre, Paris, Cabinet des Dessins. Courtesy of TASCHEN.

That Leonardo should supply the designs for smaller Madonna paintings without always executing them entirely himself was probably bound up with the fact that, around 1490, he was preoccupied with more important things. Over a period of time somewhere between 1484 and 1494, the artist was engaged in his important and most difficult project to date, the Sforza monument—the largest equestrian statue in the modern age. The monument, which was to be much bigger than life size and cast in bronze, was intended by Ludovico Sforza to commemorate the military successes of his father, Francesco Sforza, and of course to cast his own achievements in an equally impressive light.

Ludovico was not the first-born son of the Sforza family, but merely the uncle of the true Duke of Milan, who died young in circumstances never fully explained. These genealogical weaknesses led him to focus his cultural policy largely upon demonstrating the magnificence of the still young Sforza dynasty. The products of this policy included such vainglorious literary monuments as Giovanni Simonetta’s De gestis Francisci Sphortiae, an extensive building program in Milan and Pavia, the commissioning of the Last Supper, and above all the equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, which was intended to do no less than redefine its genre.

Plans for an equestrian monument were first mooted in the early 1470s, and by November 1473 they were already taking concrete shape. In a letter from Galeazzo Maria Sforza to Bartolomeo da Cremona dating from this same year, we find the first mention of a life-size equestrian statue to be sited in front of the Castello Sforzesco, the Sforza’s castle in Milan: “For we would like to have an image [imagine] of our Most Illustrious Lord and father made in his good memory, of bronze and mounted on horseback, and we want to erect it in some part of our Milan castle…The image must be as big as His Lordship and the horse of a goodly size. And if such a master is to be found, send us news, and let us know how much the costs, including the metal, the work and all other things, will amount to.”

Actual work on the monument, at first planned only in life size (“as big as His Lordship”) and hence on a modest scale, was repeatedly post-poned, however, since there were no competent artists to be found either in Upper Italy or elsewhere. Following the murder of Galeazzo Maria in 1476 and the temporary exiling of Ludovico Sforza from 1477 to 1479, the project came to a complete standstill.

As the Sforza family consolidated its power in the 1480s, however, the idea of an equestrian monument must have acquired a new relevance, to the point that Leonardo could refer to it in the speculative letter of application that he addressed to Ludovico: “Moreover, work could be undertaken on the bronze horse which will be to the immortal glory and eternal honor of the auspicious memory of His Lordship your father, and of the illustrious house of Sforza.” A good ten years later, around 1495, Leonardo would even claim that Ludovico had invited him to come to Milan to execute the monument.

There is no reliable evidence, however, to prove that Leonardo was indeed appointed specifically to build the monument, or even that he started working on the project soon after his arrival in Milan, namely in 1483 or 1484. The first authentic document relating to Leonardo’s work on the monument dates from as late as July 22, 1489, and only suggests that all is not well. The Florentine envoy in Milan, Piero Alamanno, inquired in a letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici whether there were artists in Florence who would be able to see the colossal monument through to completion, since Leonardo does not seem to be capable of it: “Since His Excellency would like to make something truly outstanding [in superlativo grado], I was advised by him to write to you and to ask you to send him one or two artists from Florence who are accomplished in this field. For although the Duke has commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to do the work, it seems to me that he is not confident that he knows how to do it.”

It is possible that Leonardo was to lose responsibility for the project or—if we interpret the letter a little more optimistically—was to be assigned some experienced assistants. Whatever the case, he must have broken off work on the monument, because on April 23, 1490, he wrote in a notebook that he had “recommenced the horse.” And indeed, over the next two years the artist worked intensively on designs for the monumental work, and above all on the technical aspects of casting it in bronze.

Finally, in 1493 he completed an enormous clay model of the horse, over seven meters(!) in height, which was exhibited that same year during the festivities to mark the marriage of Bianca Maria Sforza, Ludovico’s niece, to Emperor Maximilian I, when it formed part of the decorations in the Corte Vecchio in Milan.

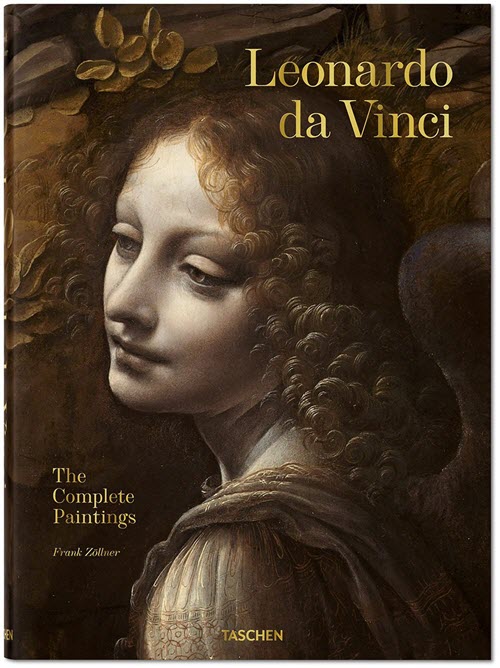

Leonardo Da Vinci: The Complete Paintings by

Pietro Marani (Taschen).

On December 20, 1493, Leonardo made another important note in the manuscript later known as the Codex Madrid II, indicating some of the serious technical difficulties into which the project had run. The pit in which the horse was to be cast, and which thus had to be at least as deep as the horse was tall, had hit the water table. Shortly after this, therefore, Leonardo must have decided to cast the horse lying horizontally in the pit, not standing upright. In view of this and other problems, the ambitious project got little further than the clay model, and in 1494 the bronze earmarked for the monument was appropriated to make cannon instead. The need to fight the French, who had marched into Italy as Ludovico’s allies and had subsequently become his enemies, meant that there were now more urgent uses for the metal. The largest monument ever designed to honor the memory of a soldier and general fell victim, characteristically, to the demands of another war.

For some years the clay model for the Sforza monument aroused the curiosity and admiration of guests and others passing through Milan, but after the arrival of the French troops in 1499 it fell into the hands of mercenaries who had little interest in art. It was used, so the story goes, for target practice by the archers, whereby it was largely ruined and eventually destroyed altogether. Like the final execution of the bronze equestrian monument, its clay model thus also fell victim to the consequences of war. Still surviving, however, are numerous sketches and preparatory studies from Leonardo’s hand, which convey a lively impression of the different stages and the technical challenges of the project.

Thus, besides a drawing for a—strangely surrealist—ironwork mould for casting the head, there are also numerous studies relating to the final appearance, movements, and proportions of the horse. The most impressive of these studies shows a rider on a horse rearing up on its hind legs. Lying beneath it is an opponent who has clearly fallen to the ground and is holding up his shield in his right hand in an attempt to ward off further attack. The motif of the rearing horse and a slain enemy lying on the ground beneath it derives from antiquity: Xenophon, in his writings on horsemanship and cavalry, describes it as a compositional formula of particular dignity (dexileos). The same motif also appeared on antique coins, where it carried imperial and military connotations; such coins were widely available in the 15th century, and we know that Leonardo was familiar with them.

The construction of a horse rearing up on two legs—especially in view of the enormous scale of the project—would have posed considerable problems with regard to the stability of the statue. In a second planning phase, therefore, Leonardo decided to use the less dramatic option of a horse striding forward. The more animated and artistically more interesting dexileos motif thus remained simply an ideal, one that Leonardo would take up once more in his Trivulzio monument, but which would only finally be translated into sculpture by the artists of the 17th and 18th century. By adopting a walking horse, the project now resembled such monuments as the so-called Regisole in Pavia, an antique equestrian statue that Leonardo went to look at in person around 1490. The artist thus made a return, in this second phase, to a more traditional formal solution.

This desire to reinforce the legitimacy of the young Sforza dynasty and cast it in a glittering light expressed itself not just in plans for spectacular monuments, which offered a welcome challenge for an ambitious artist, but also extended to smaller-scale and today less well-known areas of activity. As court artist from 1487 to 1490, Leonardo was also in charge of the design and often, too, the organization of theatrical productions and court festivities. In January 1490, for example, he designed the artistic decorations and necessary technical equipment for the “Festa del Paradiso” staged on the occasion of the marriage of Isabella of Aragon to Gian Galeazzo Sforza. This pageant was written by the court poet Bernardo Bellincioni, who like Leonardo had also come to Milan from Florence.

The primary task of the court artist was thus to cast the virtues of the members of the ruling dynasty in a favorable light and make them the subject of a piece of theatrical entertainment. The artist was thereby expected to include impressive artistic and technical effects. Anyone hoping for a successful and lasting engagement as court artist in Milan, therefore, had to bring with them a certain degree of technical expertise.

It was probably within the context of such pageants and performances that Leonardo also devised a number of allegories, in which, for example, Ludovico il Moro plays the role of protector of the official but still underage ruler of Milan, his nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza. Leonardo thereby provided the artistic backdrop to Ludovico’s political ambitions, inventing complex allegories that managed to captivate the young Gian Galeazzo even as they illustrated his calculating uncle’s thirst for power. In one of these allegories, Gian Galeazzo appears in the center of the picture as a cockerel sitting on a cage (the cockerel, galetto in Italian, is a play on his name). Lunging towards him from the right is a mob made up of foxes, a bird of prey and a horned satyr-like creature. To the left of center, Ludovico is represented by the figures of not just one, but two Virtues. Thus he is both Justice (giustizia, with the attribute of the sword) and Prudence (prudenza, with a mirror). Prudence is swinging above her head a snake and a sort of broom or brush, both heraldic symbols of the Sforza family. Prudence is holding her left hand protectively ove the cockerel, which is behind her back. Ludovico in allegorical form is thus protecting the galetto Gian Galeazzo from the mob approaching from the right.

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (Lady with an Ermine) (1489-90). Photo: Muzeum Narodowe, Cracow, Czartoryski Collection, Inv. 13. Courtesy of TASCHEN.

As artist to the Sforza court and its festivities, Leonardo was once again in demand as a painter. The creative talents that he had previously brought to pageants and allegories found their most impressive expression in his Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, in which Leonardo broke away from the compositional format prevailing in Upper Italian portraiture of his day. Thus he did not adopt the profile view typically employed in nuptial portraits, since he did not have to portray Cecilia as a bride, but as the mistress of Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo also distanced himself from the traditional, rather static pose in which head and upper body face the same way. In the Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the two are angled in different directions: the upper body is turned to the left, the head to the right. The painting thereby corresponds to the dynamic style of portraiture that Leonardo was already working towards in his Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci and which is explicitly formulated in his treatise on painting. This desire to infuse the portrait with a sense of movement emerges not only in the positioning of Cecilia’s head and body, but also in the dynamic pose of the ermine, which echoes that of the young woman. Cecilia’s elegantly curved but at the same time somewhat overly large hand in turn corresponds with the figure of the ermine.

The ermine was a symbol of purity and moderation, for according to legend it abhorred dirt and ate only once a day. Leonardo refers specifically to these qualities of the ermine in his writings, where he makes notes on the allegorical significance of other animals, too. The legendary purity of the ermine is also the starting-point for a pen drawing probably dating from around 1490. In this allegory, Leonardo illustrates the traditional belief that an ermine would rather be killed than sully its white fur in dirty water as it flees.

From the late 1480s onwards, moreover, the ermine could also be read as an allusion to Ludovico Sforza, who used it as one of his emblems. In the figurative sense, therefore, this portrait shows Ludovico, in the shape of his symbolic animal, being tenderly stroked in the sitter’s arms. The comparatively complex symbolism of this portrait, and the delicate situation it portrays, have their explanation in the fact that the young woman was Ludovico Sforza’s favorite mistress.

Detail of Portrait of an Unknown Woman (La Belle Ferronière) (c.1490–1495). Photo: Musée du Louvre, Paris, Inv. 778. Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Alongside the Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, Leonardo’s early works as court painter also include the so-called Belle Ferronière, whose attribution to Leonardo is today rarely doubted. In compositional terms, the painting is closely related to a portrait type found across northern Italy, in which a stone parapet separates the viewer from the pictorial space. This same type surfaces in the works of Antonello da Messina and Giorgione, for example, and is ultimately indebted to earlier Flemish models. Uncertainty cotinues to reign, however, over the dating of the portrait and the identity of the sitter. The portrait may show Lucrezia Crivelli, another of Ludovico Sforza’s mistresses.

This is an edited excerpt from Frank Zöllner’s new book, Leonardo Da Vinci. The Complete Paintings, published by TASCHEN.