People

How Grada Kilomba Turned Her Study of Psychoanalysis and PTSD Into an Artistic Practice That Confronts Collective Trauma

The 'modern-day griot' is making waves with a new installation in Lisbon and a solo exhibition in Brooklyn.

The 'modern-day griot' is making waves with a new installation in Lisbon and a solo exhibition in Brooklyn.

Caroline Elbaor

Grada Kilomba does not shy away from difficult conversations. Armed with a PhD in philosophy, a degree in psychoanalysis from the Instituto de Psicologia Aplicada, and a background in treating people with post-traumatic stress disorder, the multidisciplinary artist is especially qualified to confront issues of trauma and memory, exploring how these relate to racism, sexism, and colonialism and its aftermath. The Portuguese artist’s work—which encompasses film, installation, critical writing, and performance—is highly emotional; Kilomba directly addresses the pain that is inherent to the human experience.

“I don’t work in morality; I work in emotionality,” the Berlin-based artist pronounced while speaking with Artnet News. In her latest work, O Barco/The Boat, on view through October 17, Kilomba has presented a large-scale installation—her first foray into the medium—at the Museum of Art, Architecture, and Technology (MAAT) in her native Lisbon.

Grada Kilomba, O Barco/The Boat (2021), currently on view in Lisbon outside the Museum of Art, Architecture, and Technology (MAAT). Photo: By Creative Agency (Pedro Machado).

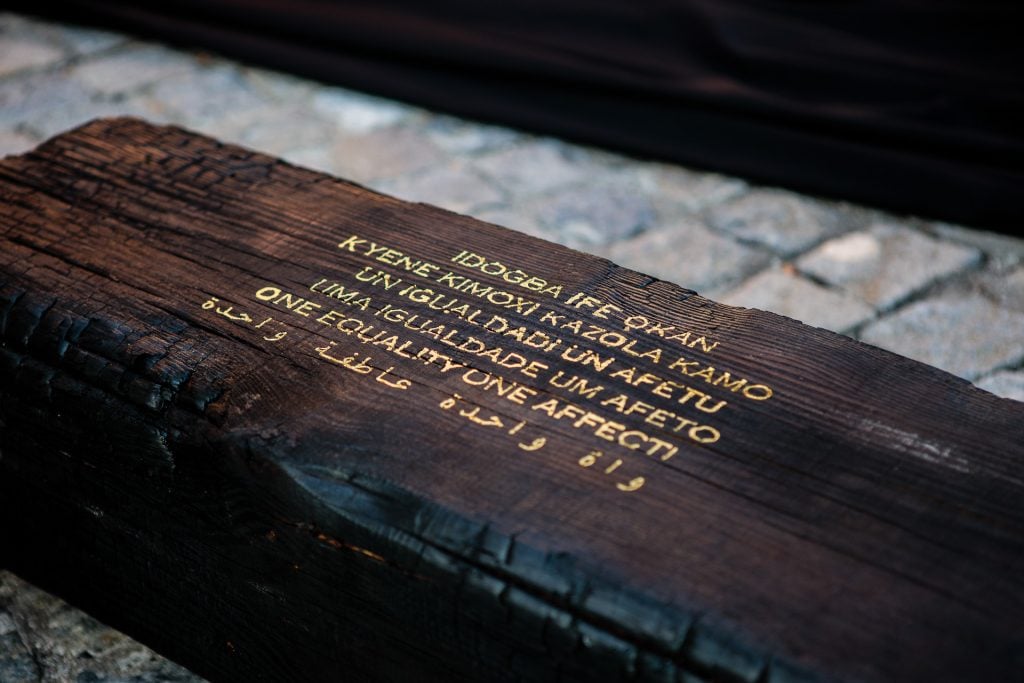

Consisting of 140 burnt wooden blocks arranged in the shape of a ship’s belly, the public intervention occupies a 32-meter stretch alongside the Tagus River. Eighteen of the blocks are emblazoned with original poetry by Kilomba that has been translated into languages ranging from Yoruba and Creole to Portuguese and Arabic. Verses include, “One equality / one affect,” and “One load / one story.”

It is no coincidence that this new work, created to pay tribute to the countless enslaved peoples rendered invisible throughout history, sits within eyesight of the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, a prominent landmark whose title translates as “monument of the discoveries.” Portugal was the first European nation to initiate the Atlantic slave trade in 1444, and remained its leader for 79 years after expanding the practice to the whole of the West African coast in 1455. Enslavement within Portuguese colonies was only fully abolished in 1869. Kilomba traces her own origins back to the West African islands of São Tomé e Príncipe, which served as a way station for slave ships en route to Brazil.

Grada Kilomba, O Barco/The Boat (2021, detail). Photo: By Creative Agency (Pedro Machado).

“We create a narrative of glory and adventure and exploration in monuments,” Kilomba observed. “The boat is a symbol and metaphor for 500 years of history and glory, with white, patriarchal men being celebrated. I wanted to create a sculpture-installation that revealed what these colonial boats did: how did they erase so many bodies from the narrative?”

To stand within the assemblage of charred blocks, delicate yet overwhelming in number, is sobering to the point where it feels as if one is violating hallowed ground. This aligns with Kilomba’s intent to “interrupt the public space” with a reminder of the soil’s history of violence. She was offered the opportunity to mount O Barco/The Boat at institutions in New York and Italy, but turned them down in favor of her Portuguese roots, and to honor those in Lisbon whose ancestors also suffered under colonial enslavement.

For the September unveiling of O Barco/The Boat, Kilomba organized an operatic performance enacted by a troupe of locals, who, like her, hail from African diaspora communities. Kilomba describes it as a ritual and means of healing. “This history is a wound with a story that was never properly told. When we don’t tell history properly, it repeats itself.” The artist posits that it is “only through these ceremonies and retelling” that recovery can occur.

Still from Grada Kilomba, Illusions Vol. II, Oedipus (2018). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, Cape Town, and London.

The subject matter is heavy stuff, which has garnered Kilomba (who is represented by Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and London) critical admiration as her profile continues to grow. Volumes I and II of her best-known work, the Illusions trilogy—which retells Greek myths through a postcolonial lens, using video, performance, theater, music, and choreography—were acquired by the Tate last year.

In addition to O Barco/The Boat at MAAT, Kilomba is also currently the subject of a solo exhibition, on view through October 31, at the new Amant art center in Brooklyn, which marks her U.S. debut and inaugurated the nonprofit’s program this past July. “Grada’s work responds to issues and problems that are timely and urgent. Moreover, she’s a very compelling storyteller,” said Ruth Estévez, artistic director at Amant. “She shows no fear of expressing vulnerability while also assuming a position of responsibility within this chaotic current moment.”

Kilomba often describes herself as a modern-day griot, a figure whose role in West and Central African societies was to reveal forgotten stories, or reposition oft-told tales in a contemporary light. Her 2019 work Illusions Vol. III, Antigone, continues in this vein, recasting the familiar story in the tradition of African oral histories to create a powerful meditation—not only on justice and resistance, as in the original, but also on gender. The artist exhibited this final Illusions chapter at Sweden’s Bildmuseet in Umeå, which had commissioned the piece. Katarina Pierre, the director and curator, made the decision to support the new work after seeing Kilomba’s show at Avenida da India Gallery in Lisbon.

Installation view of “Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters” at Amant, Brooklyn, NY. Photo: Shark Senesac. Courtesy Amant.

“I found myself completely blown away by the artistic quality,” Pierre told Artnet News. “She is an incredible artist in all respects. In my view, she is one of today’s most interesting artists.”

This acclaim is not limited to her visual arts: Kilomba’s 2008 book, Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism, has been translated into several languages and was named the most important piece of nonfiction literature in Brazil in 2019. Plantation Memories is a compilation of various textual formats, pairing theory with prose and poetry to contest the white, patriarchal mindset as the current norm of thought.

Pierre praised Kilomba’s ability to marry text and art-making. “She transforms her intelligent texts into a visual language,” the curator said. “She makes her words come to life, in close collaboration with actors, dancers, and musicians – a format she masters brilliantly. She gives body, voice, and image to her own texts.”

The artist emphasized that all her work begins with writing. “I’m very concerned with language,” she said when describing her process. “I start with my work in psychoanalysis, which I believe is the language of the unconscious. I wanted to create a work that is aware of the power and violence that occur in language. European languages are rich in oppression.”

Ultimately, this unspoken language of the mind is what produces such poignant and striking work. Regardless of individual experience, pain is universal; like giving air to a wound, Kilomba’s voice provides a reprieve for collective and deep-seated trauma.