People

An Artist Representing Grenada in the Venice Biennale Has Had to Launch a GoFundMe Campaign to Help Pay for the Pavilion

Frank fled Grenada when he was 16. Now he’s representing the tiny country on the art world's biggest stage.

Frank fled Grenada when he was 16. Now he’s representing the tiny country on the art world's biggest stage.

Taylor Dafoe

Most artists who earn the honor to participate in the Venice Biennale also have the benefit of having their sponsoring countries foot the bill. Some countries, though, especially smaller ones with less funding for the arts, aren’t so lucky.

Grenada, which is participating in the Biennale for the third time next year—tying them with Cuba for the most appearances for a Caribbean country—belongs in the latter category. The Caribbean island selected four artists to represent them this year: Shervone Neckles, Dave Lewis, Amy Cannestra, and Billy Gerard Frank. Each will be addressing the theme of “Epic Memory,” an idea taken from the Nobel acceptance speech of Caribbean writer Derek Walcott. Yet, in addition to creating this work, all four participating artists are also tasked with raising the money to make the trip to Venice.

That’s a big task, one that will see all four artists calling on every favor they can to make the cut. Frank, a New York-based filmmaker and multimedia artist, is doing so in a more public manner. Last month, he launched a gofundme campaign to raise a portion of the money.

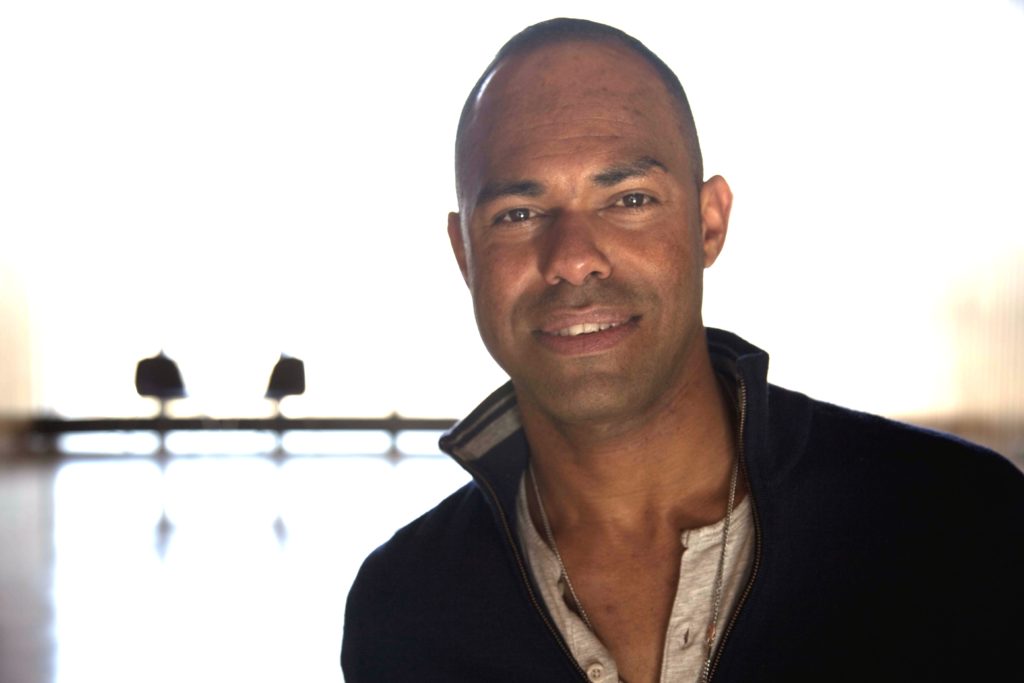

Billy Gerard Frank, Love Insouciance. Courtesy of the artist.

The idea came about after the lineup for the pavilion was announced, when a number of his close friends asked how they could support him.

“I thought the easiest way to do it was through a campaign like this,” he tells artnet News. “It’s a way of letting people know about me, the work that I’m doing, and to promote Grenada’s participation in the Biennale. I think a lot of artists shy away from putting themselves out there and instead depend a lot on organizational support and grants. In these times that we’re living in, one has to use all the platforms available to us to not only promote work but to fund it.”

He’s seeking to raise $10,000 on the platform—just a fraction of the $70,000 in total he needs to raise for travel, shipping, and production of the work itself. At the time of this article’s writing, he’s raised $2,095.

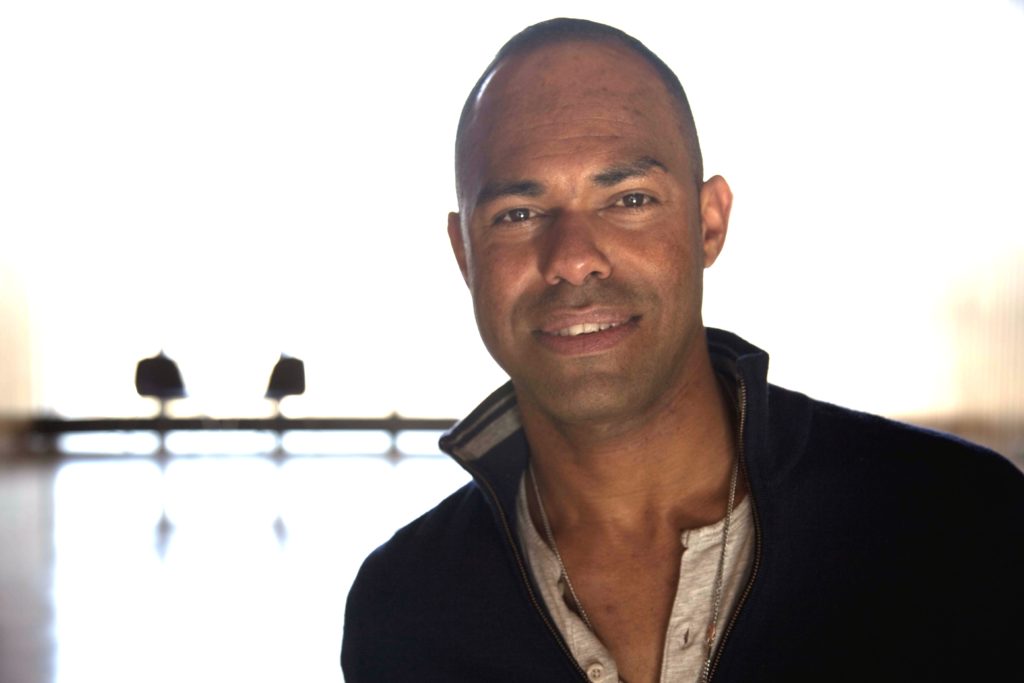

Billy Gerard Frank, PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I DON’T WANT. Courtesy of the artist.

For Frank, representing his home country on the art world’s biggest stage is both a source of pride and internal conflict.

“I have a sense of estrangement from the Caribbean,” he explains. “As a young gay man, it wasn’t really a pleasant experience growing up there.”

He left home when he was 16 and for 18 years, and did not return for many years. That changed two years ago when his father became sick and eventually passed away.

“I remember his vacant, glassy eyes and foreboding countenance, turning to me on the fishing boat and saying, ‘Boy, you are a real good-for-nothing you know, coming back to rob me of my last penny,’” Frank recalled in his proposal. “These words were the only and last words spoken between us.”

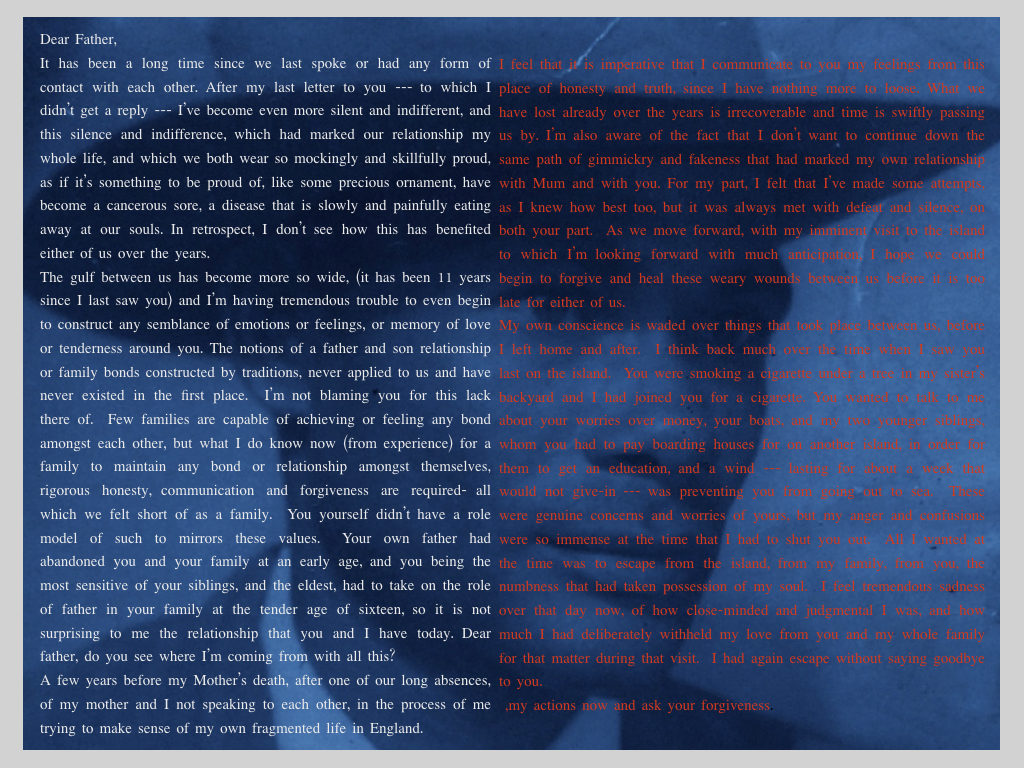

Film still from Frank’s film, Absence of Love (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

Much of his practice is about this very issue, coming to terms with his own past—growing up in a homophobic culture with a distant, if not completely absent father.

“Personally, a lot of my practice as an artist is about reconciling my relationship with my family, the Caribbean, and my own colonial past. My art, my writing—it all deals with this kind of collective trauma and memory. My way of reconciling and healing those memories is through making art.”

After his return to Grenada, Frank made a short film called Absence of Love in which he explored his relationship to his father through the lens of two fictitious brothers processing the loss of their own father.

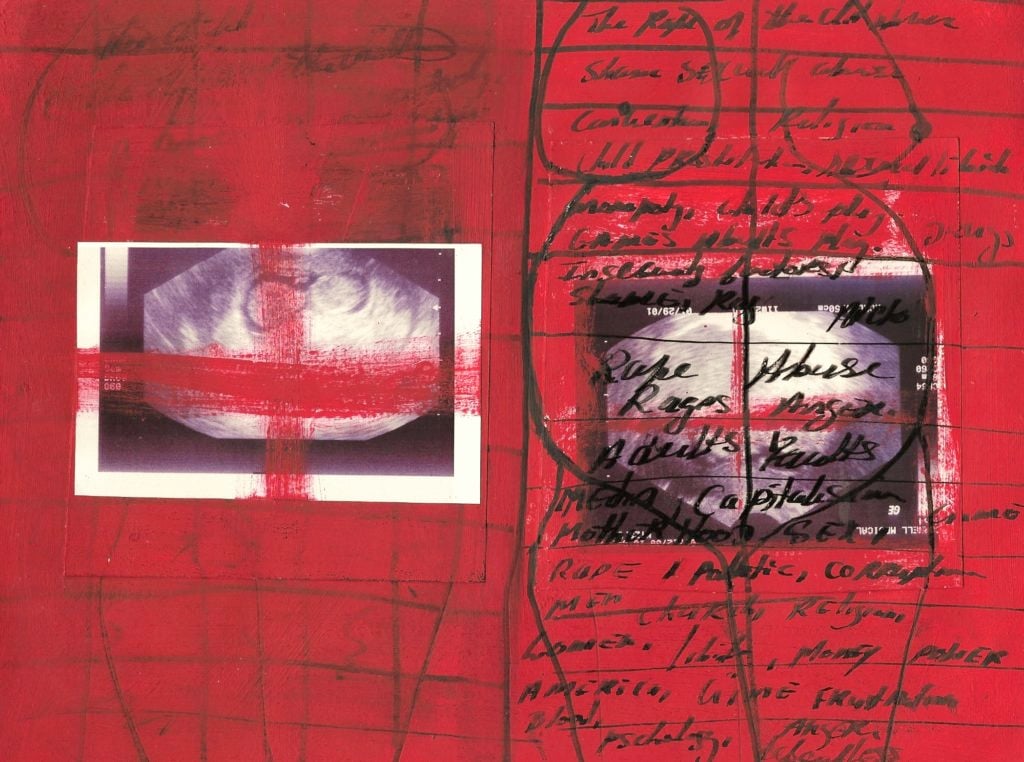

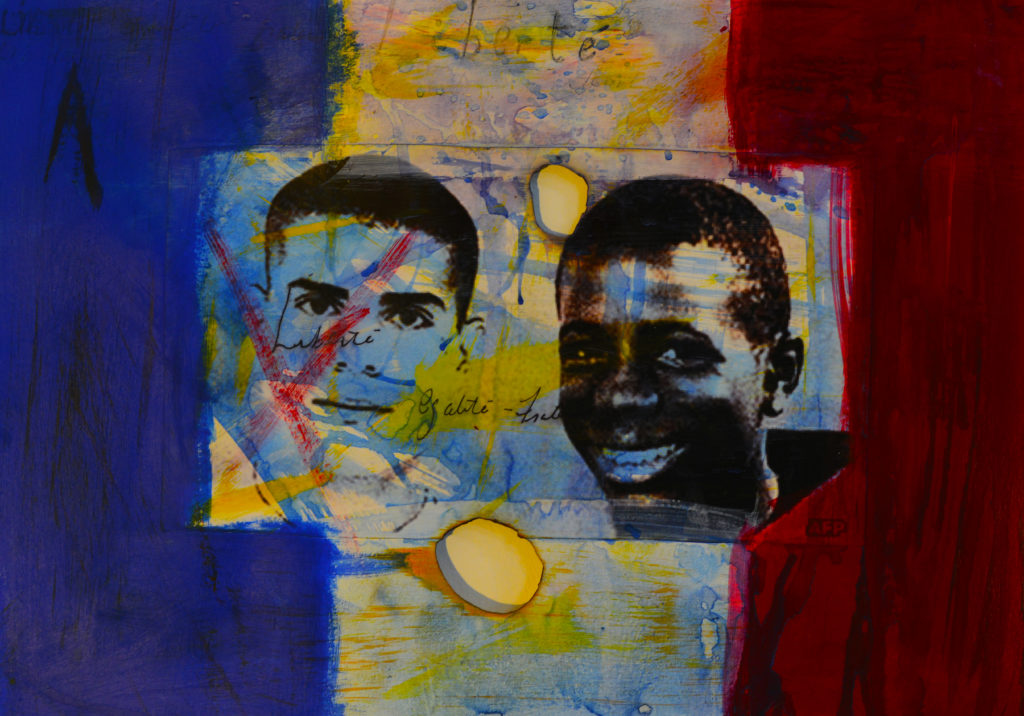

Billy Gerard Frank, Fin de Dialouge 2. Courtesy of the artist.

Building on this work, the multimedia project he is preparing or Venice, titled 2nd Eulogy: mind the gap, explores similar territory, mining his relationship with his dad and trafficking in themes of colonialism, identity, and exile. He’ll be sharing a room a room with fellow artist Neckles, whom he’s been collaborating with since this summer.

“When I was younger, I was coming from a place of anger,” Franks says. “That anger allowed me to leave home and pursue the things I’ve been able to pursue in my life. If I didn’t have that anger to fuel me, I don’t think I would have been able to leave the island. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned that I have space in my heart for compassion and love and deep appreciation for the place I come from, even if I have a complicated relationship to it.”