Art World

Researchers Discover an Ancient Stone Carving So Detailed It Could Alter the Course of Art History

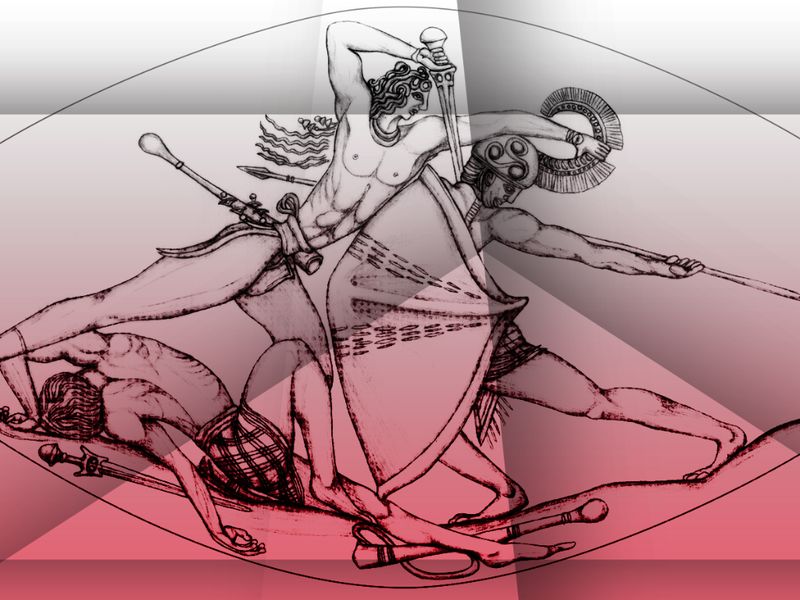

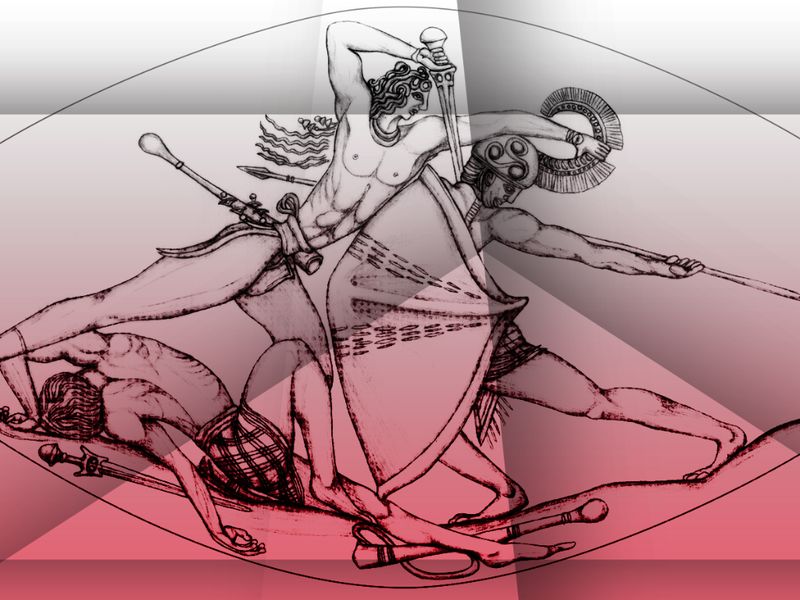

The tiny carving has been dubbed the Pylos Combat Agate.

The tiny carving has been dubbed the Pylos Combat Agate.

Sarah Cascone

It’s the tomb that keeps on giving. More than two years since its discovery, a treasure-filled Greek tomb has offered up perhaps its most significant find to date: a Minoan stone carving so sophisticated and detailed that it has forced art historians to reaccess their understanding of ancient artwork.

Dubbed the Pylos Combat Agate, the sealstone carving is just an inch and a half wide, but its impact on the study of prehistoric art may well be enormous.

“This seal should be included in all forthcoming art history texts, and will change the way that prehistoric art is viewed,” said Sharon Stocker, a senior research associate in the University of Cincinnati classics department, in a statement. She believes the stone, made by the ancient Minoans, is the finest-known example of prehistoric glyptic art produced in the Aegean Bronze Age.

Excavation leaders Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis have worked in the Pylos region of Greece for 25 years. Photo courtesy of the University of Cincinnati.

The intricately carved gemstone “shows that the [Minoan’s] ability and interest in representational art, particularly movement and human anatomy, is beyond what it was imagined to be,” added her husband, department head Jack Davis, a professor of Greek archaeology. “The representation of the human body is at a level of detail and musculature that one doesn’t find again until the Classical period of Greek art 1,000 years later.”

“Looking at the image for the first time was a very moving experience, and it still is,” Stocker noted. “It’s brought some people to tears.”

The landmark find shows a warrior battling against two adversaries, killing one enemy, the other already dead at his feet.

It’s the latest archaeological treasure to come out of the Griffin Warrior Tomb, discovered by the Davis- and Stocker-led team from the University of Cincinnati at Pylos in 2015, which was touted as the most significant Greek archaeological discovery in half a century.

A recreation of the face of the Griffin Warrior Tomb’s occupant. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati.

The tomb is believed to have been the final resting place of a remarkably wealthy Mycenaean warrior or priest. (A team of specialists has since recreated his probable appearance based on the dead man’s skull.)

The Griffin warrior was buried around 1500 BC, about the time that the Mycenaeans, from mainland Greece, defeated the Minoans, a more advanced civilization from the island of Crete that had a massive influence on the Greek world. The presence of many Minoan artifacts in the tomb suggests a previously unknown degree of exchange between the two cultures.

This gold ring with a Cretan bull-jumping scene was one of four solid-gold rings found in the Griffin Warrior Tomb. Photo courtesy of the University of Cincinnati.

To date, archaeologists have catalogued some 3,000 burial objects from the Griffin Warrior Tomb, including a bronze sword with a gold-embellished ivory hilt; four solid gold rings; silver cups; over 1,000 carnelian, amethyst, jasper, and agate beads; fine-toothed ivory combs; and a golden dagger.

“The whole tomb contains such a wealth of riches that it’s really very stunning,” Stocker told artnet News. “It’s extremely rare to find a tomb that wasn’t looted during antiquity or in modern times.” Amid the treasures, the seal, heavily encrusted with limestone that took over a year to clean, was almost overlooked, a tiny, apparently insignificant object.

The Pylos Combat Agate before it was cleaned. Photo courtesy of Alexandros Zokos/the University of Cincinnati.

“It was after cleaning, during the process of drawing and photography, that our excitement slowly rose as we gradually came to realize that we had unearthed a masterpiece,” wrote Stocker and Davis in the journal Hesperia, according to the New York Times.

“The Pylos Combat Agate is one of the finest objects that we have found in the Griffin Warrior tomb,” Stocker added. “The craftsmanship is something that you rarely see in the Minoan and Mycenean world. It’s virtually unparalleled.”

Excavation leader Sharon Stocker at the site of the Griffin Warrior Tomb. Photo courtesy of the University of Cincinnati.

The fine details on the stone carving, made all the more difficult to decipher by banding in the agate stone, are so minute that some of them, as small as a half a millimeter in length, can only be seen with the assistance of magnification. Davis described the artwork as “incomprehensibly small.”

In Crete, such sealstones would be used to make impressions that would mark ownership. Placed on a bottle of wine, for instance, it would indicate that the seal was unbroken. In contrast, the Myceneans treated such sealstones as decorative objects, wearing them as jewelry. The Griffin Warrior was found sporting another sealstone pendant as a bracelet.

Less is known about how such an object might have been made, as there is no evidence of magnification at existing archaeological sites for sealstone workshops in Crete. Theories include the use of rock crystal, or artisans with exceptional close-up vision, perhaps due to nearsightedness. Agate is also quite hard, making it difficult to carve.

“It is indeed a mystery how they did it,” said Stocker. “It’s amazing to hold and look at it.”