People

artnet Asks: Author and Gallery Owner Steve Hauk on Fiction and Legacy

Hauk Fine Art gallery owner’s reimagining of John Steinbeck and the contemporary interest in early California art.

Hauk Fine Art gallery owner’s reimagining of John Steinbeck and the contemporary interest in early California art.

Artnet Galleries Team

Steve Hauk’s passion for the work created within collaborative artistic and literary communities has reached a pinnacle with Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, illustrated by C. Kline. Prior to the publication of his book on the beloved author, Hauk penned plays covering California Impressionist artists Granville Redmond and E. Charlton Fortune. An avid writer and reader, Hauk is also the owner of Hauk Fine Arts in Pacific Grove, CA, where he and his late wife have dedicated themselves to the art of the Monterey Peninsula.

The man of many hats sat down with artnet News to talk about the crosspollination of art and literature in his own life, and the internet’s role in preserving and unearthing history.

Tell us about your background in art and what led you here.

My background in art comes from my late wife Nancy, who was an art history major at Connecticut College as well as a fine artist. Nancy taught me to appreciate and love art while I pursued a career as a journalist—crime reporter, features writer, sports writer, drama critic, columnist. Nancy broke down test biases for McGraw-Hill’s California Testing Bureau, traveling the country to work with inner city school districts, painting when she could. About 25 years ago, we decided to open a gallery while still holding our jobs.

What type of art does your gallery focus on?

We began by dealing with what would become known as early California art, though in some ways the term is misleading—most of the artists came from Europe, Asia, and throughout the United States. Few were natives of California. The appeal was being able to paint out of doors year round, something difficult to do in, say, Sweden or Maine. Realizing these artists might not have become known if galleries hadn’t represented them in their day, we soon expanded to show the work of contemporary artists. But we didn’t want a repeat of what the early California artists had painted—we wanted artists who made their own statements.

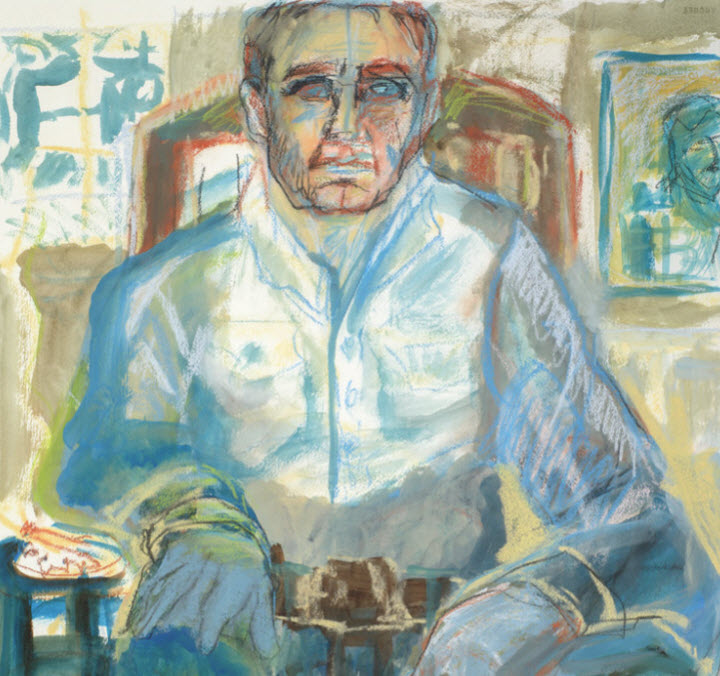

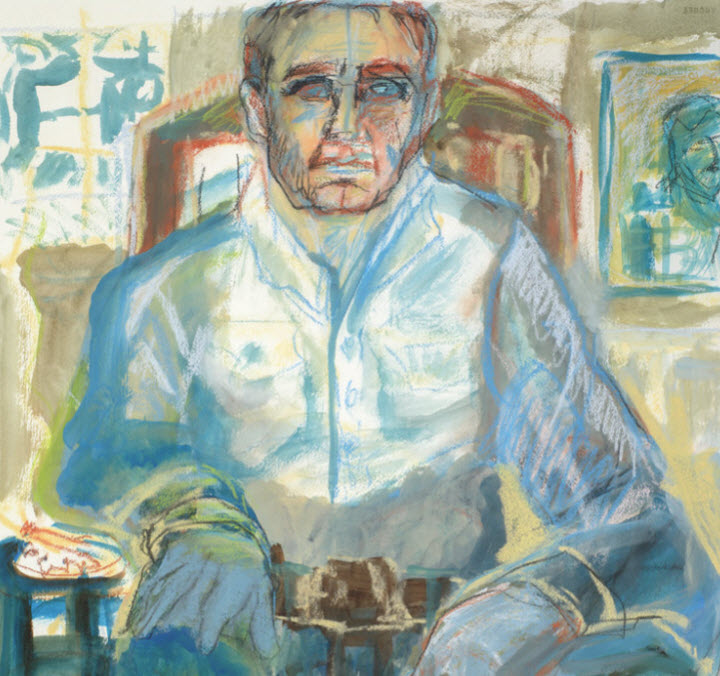

Judith Deim, Nocturne Espane. Courtesy of Hauk Fine Arts.

Aside from being an art dealer, you are also a writer. How do you manage to balance both of those responsibilities?

Balancing writing with running a gallery has proved advantageous. Galleries can be fertile grounds—you have work on display, people come in, the art opens up discussion, interesting things get said, writing themes occur.

My writing two award-winning documentary films on photography and art came through the gallery and the Monterey Museum of Art. The Roots of California Photography—The Monterey Legacy and Time Captured in Paintings—The Monterey Legacy were both narrated by the late Jack Lemmon and have been telecast on public television.

Since you started, what have been the biggest changes in the gallery market?

Beginning in the 1980s, early art was the rage in California. The 2007–2008 recession took some air out of the market. But it is coming back, and the demand has increased for the more powerful of the early artists such as Armin Hansen, Guy Rose, and E. Charlton Fortune.

Fortune’s prices, for example, are beginning to rival those of the greatest American women artists. I wrote a play on her, Fortune’s Way, or Notes on Art for Catholics (and Others), that has been given staged readings from the Carmel Mission in 2010 to next January at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento by the Capital Stage, tying in with an important traveling museum exhibition of Fortune’s work, “E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit.”

Another play, The Floating Hat, is on the relationship of Charlie Chaplin and deaf California artist Granville Redmond, whose paintings regularly sell for six figures; this play is held by Gallaudet University.

You recently wrote a book—Steinbeck: The Untold Stories. What influenced you to explore this topic?

I recently had a book published by Steinbeck Now on Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck. Much of Steinbeck: The Untold Stories came through the art world and the gallery. I had co-curated the inaugural art exhibition at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, CA. Then people began showing up at the gallery with stories, letters, and documents pertaining to Steinbeck’s life. One of the most telling was from 1942—Steinbeck applied for a New York State pistol license. He needed to be armed, Steinbeck wrote in the application, for “self-protection.” The danger likely came from one or more hostile individuals in California, but since Steinbeck was in New York, he obviously thought it important to be licensed there.

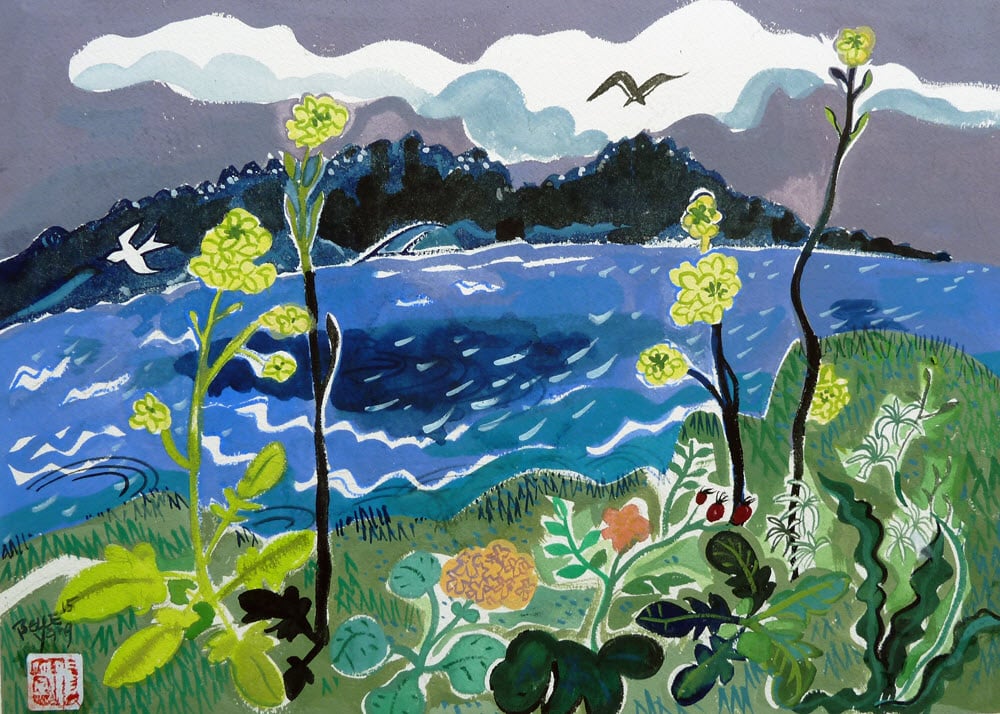

Belle Yang, Point Lobos. Courtesy of Hauk Fine Arts.

I soon learned Steinbeck had had strong relationships with artists all his life. Henry Varnum Poor was one of four character witnesses signing the gun license application. Steinbeck was the subject of numerous portraits by painters and photographers, including James Fitzgerald, Judith Deim, Ellwood Graham, as well as Sonya Noskowiak in California, Poor and Yousuf Karsh in New York, and Bo Beskow in Sweden. He found them to be people he could trust. In the spirit of this kind of artistic collaboration, the stories in my book are illustrated by another superb artist, C. Kline.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of publishing this book?

Basically the stories in the book are fiction rooted in fact. Each story’s core is true, but getting there is fictional. The book’s a study of the emotional price the author paid for what he was writing. Almost all great writers encounter hostility, but because he was writing about labor issues and the dangers that presents, Steinbeck paid a greater price—including being driven from his California home—than other major American writers of his time such as Hemingway, Cather, and Faulkner.

In today’s world, social media is a key source of information. As a writer for the Steinbeck Review and Steinbeck Now, have you found that social media helps in keeping Steinbeck’s legacy alive?

The internet’s been important to the gallery and my writing. Several contacts on Steinbeck have come through related websites, including artnet. It doesn’t hurt that Steinbeck is mentioned more frequently by editors, journalists, and bloggers than any other American author of the last century. Issues he dramatized have returned, or never went away. The annual Steinbeck bibliography contains more online material than printed books or articles. Several stories in my book I first wrote in essay form for Steinbeck Now or the Steinbeck Review.

Do you have a favorite artist? A favorite author?

My favorite historic artists include E. Charlton Fortune, Gottardo Piazzoni, and any Rembrandt self-portrait. My favorite writers are Steinbeck, Chekhov, and Tennessee Williams.

The artnet Gallery Network is a community of the world’s leading galleries offering artworks by today’s most collected artists. Learn more about becoming a member here, or explore our member galleries here.