Art World

The Guggenheim Just Restored Its First Web Artwork. Here’s How.

Overcoming the unique conservation challenges of Internet art.

Overcoming the unique conservation challenges of Internet art.

Sarah Cascone

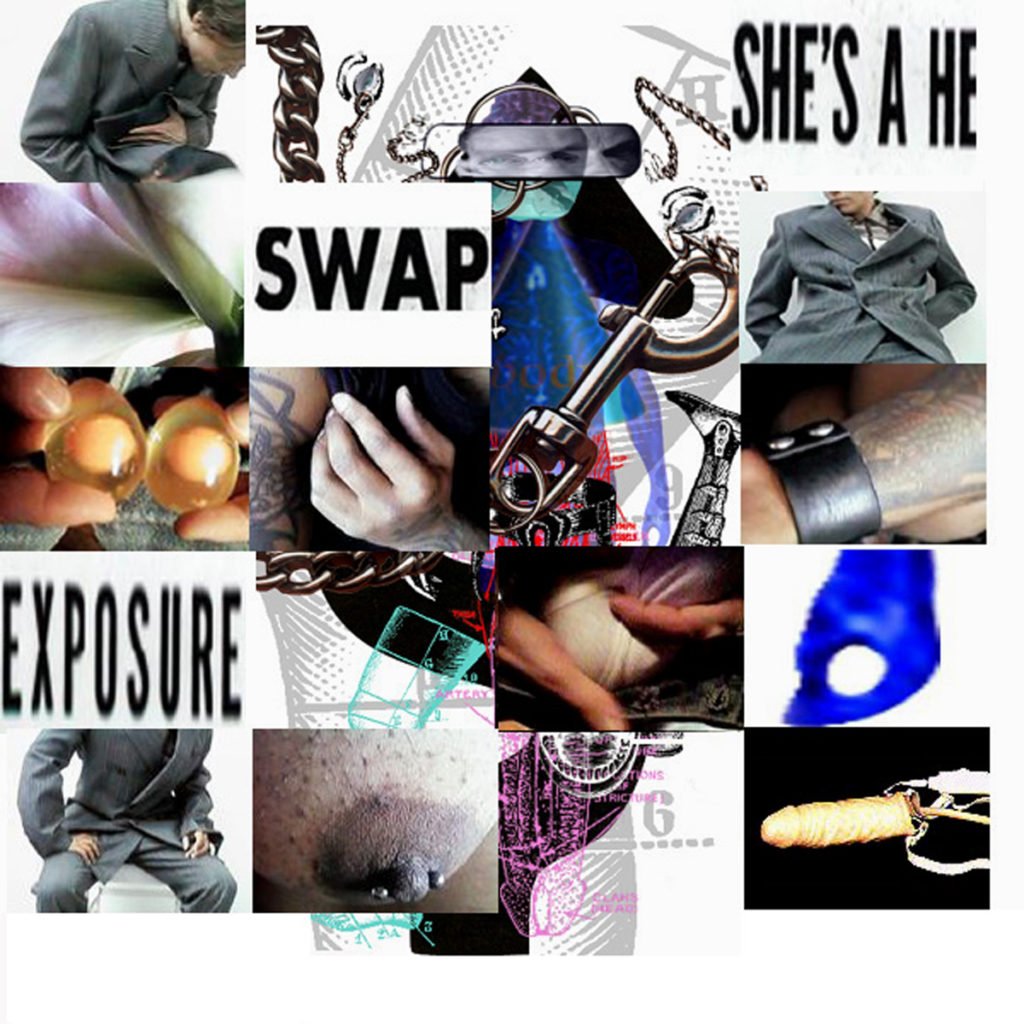

Even the Internet has ruins worthy of preservation. Amid remnants of the early web, the Guggenheim has restored Shu Lea Cheang′s Brandon (1998–99), the first online artwork to join the New York museum’s permanent collection. The long-defunct website, commissioned by the Guggenheim in 1998 and hosted at http://brandon.guggenheim.org, is the first digital artwork to be restored by the museum.

Brandon, a response to the tragic 1993 rap and murder of Nebraska trans man Brandon Teena, was a “one-year narrative project in installments,” which saw numerous artists and programmers contribute to the project during its run. There were online chat rooms that allowed the public to add to the piece, as well as live “simulcast” events at the Society for Old and New Media in Amsterdam and the Guggenheim’s former Soho space. Brandon became an important repository of LGBTQ+ discourse and culture, and its subject matter is of course still resonant and timely today.

“It was a very brave step at the time, a very pioneering and visionary step,” Joanna Phillips, the museum’s conservator of time-based media, told artnet News of the work’s acquisition. “The piece was also groundbreaking at the time because it included many performative aspects… There was a very early web cam connection, so people in Amsterdam and New York could see and hear each other. It pushed the limits of what communication technology could achieve at the time.”

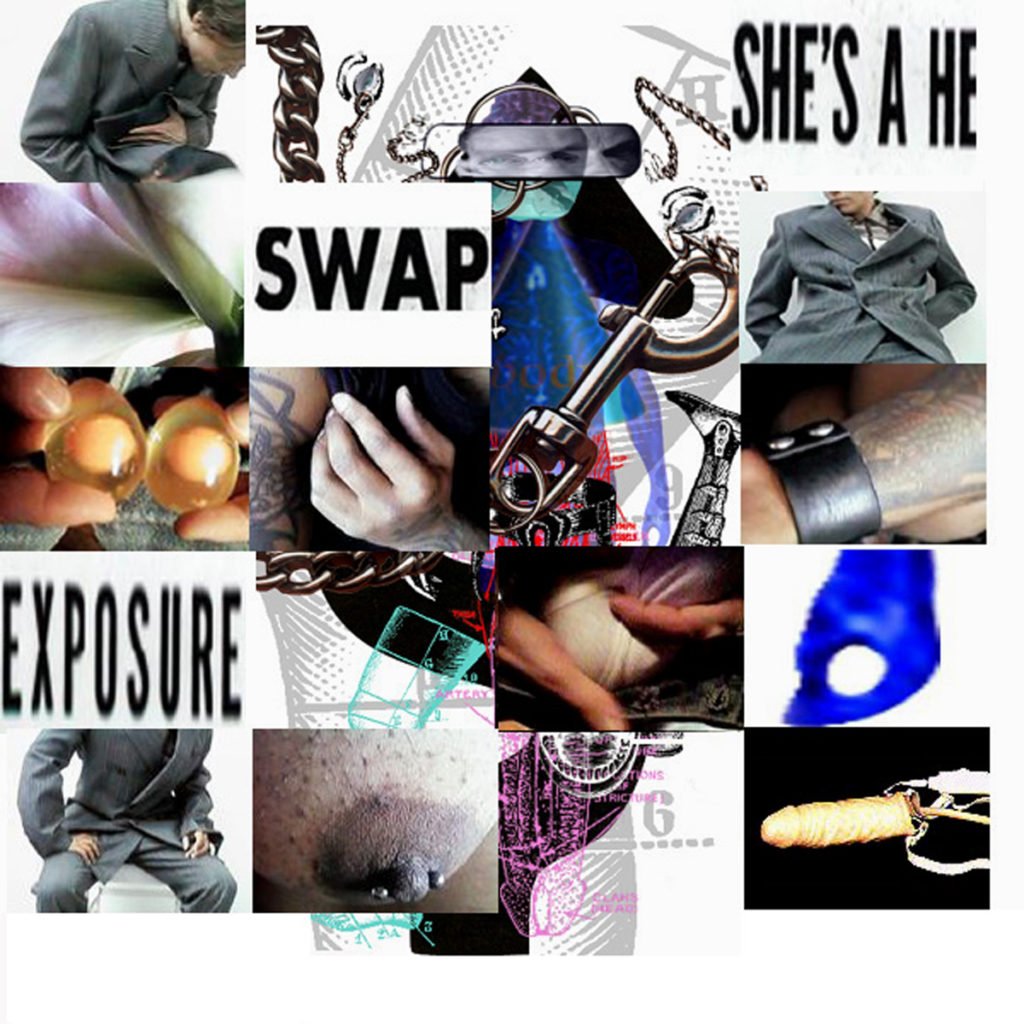

Shu Lea Cheang, Brandon (1998–99). Courtesy of the Guggenheim, © Shu Lea Cheang.

When artists first began experimenting with the Internet, little thought was given to the conservation of these online artworks. Today, technology has developed in such leaps and bounds that works that were once cutting edge have quickly become outdated, giving rise to a whole new fleet of issues and challenges for conservators.

“These pieces have very special needs; software becomes obsolete, hardware breaks down,” said Phillips. “In the museum world there is not a lot of precedent for dealing with these works.”

Enter the Guggenheim’s Conserving Computer-Based Art (CCBA) initiative, founded this past fall with the New York University Department of Computer Science, which has collaborated with the museum since 2014. CCBA aims to analyze, document, and preserve the collection’s 23 computer- and software-based artworks. CCBA, led by Phillips, and NYU professor Deena Engel, worked with CCBA fellow Jonathan Farbowitz and NYU computer science students Emma Dickson and Jillian Zhong to return Brandon to its former glory.

When the project began, “many parts of Brandon didn’t operate any more,” said Phillips. “What we were dealing with outdated web technology and we had a find a solution to make the piece accessible to the public today.”

NYU computer science students Emma Dickson (left) and Jillian Zhong present their source code analysis of Brandon and discuss their migration prototypes with Guggenheim staff and invited guests in the Guggenheim’s Time-Based Media Conservation Lab. Courtesy of the Guggenheim/photographer Kristopher McKay.

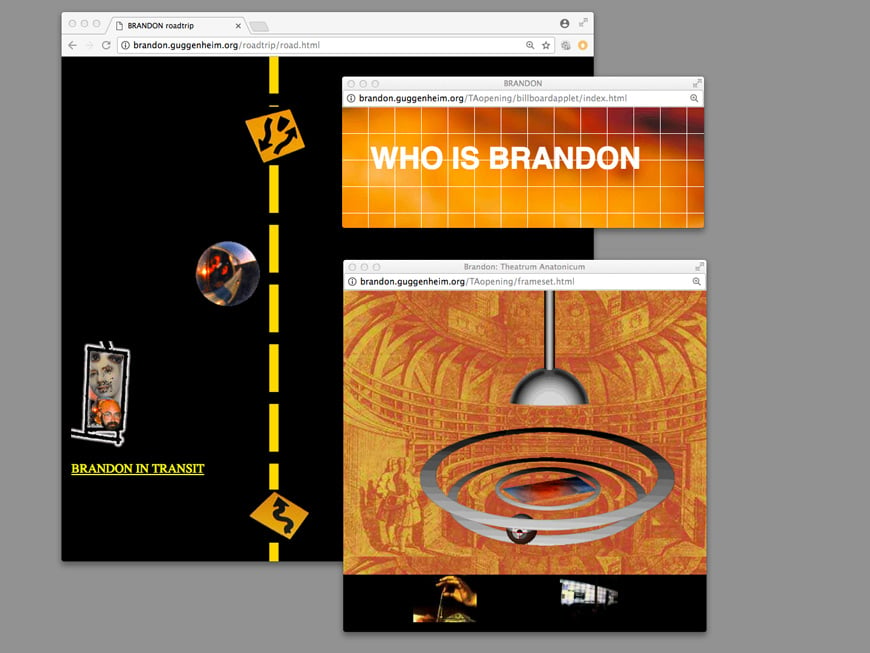

Students spent two semesters carefully combing through the website’s source code to understand its intended user experience. “Brandon is extremely complex,” Phillips noted. “There’s a whole hidden research archive buried within the code.”

“The movement, the speed, the interactivity, what happens when you mouse over what part of the site, what functions are called into action, what are the colors… all of this can be found inside the code,” she added. “Looking a the source code was key to seeing what the behaviors were supposed to be like.”

In the years since Brandon′s creation, many of its components had stopped working, thanks to advancements in technology. Its programmers, for instance, had developed eleven unique Java applets (mico applications that work within a browser) that no longer displayed correctly. Modern browsers, such as Google Chrome, stopped supporting Java in 2015.

“We were dealing with outdated web technology and we had a find a solution to make the piece accessible to the public today again,” said Phillips. One trick employed to repair the broken code—all written by hand back in those days—was the use of animated GIFs in place of the outdated Java code.

The conservation intervention in Brandon’s source code is documented with code annotation, color-coded here in light grey. Courtesy of the Guggenheim/screen shot: Jonathan Farbowitz,

The original effects of other outdated HTML elements were recreated through more modern code like JavaScript and CSS (the software equivalent of rigging an ’84 Macintosh display on a 2017 MacBook). The project has fully restored the website’s 82 pages and popup windows, once again providing access to Brandon as it would have been experienced back in 1999. “Technically speaking, the restoration effort was a migration of one technology to another,” Phillips added.

This process required the creation of new protocols to ensure adherence to conservation ethics, so that additions to an artwork are reversible. The CCBA team was careful not to delete any of the original Brandon programming, creating a duplicate version of the site that annotates all additions and ensures that broken or obsolete code would no longer be executed. Additionally, all of the restoration work—which took four months to complete—and the decisions behind it has been recorded in a treatment report.

“The artist,” noted Phillips, “is very excited that the piece can finally be experienced again.”