Art History

Klimt’s Glittering Ode to Love Scandalized Turn-of-the-Century Audiences. Here Are 3 Things You May Not Know About ‘The Kiss’

Klimt painted his masterpiece in the aftermath of a major professional crisis.

Klimt painted his masterpiece in the aftermath of a major professional crisis.

Katie White

In a glittering gold realm, two lovers, a man and a woman, embrace on a flowery field that ends beneath the kneeling woman’s bare feet. The man leans down to kiss his beloved, his face turned away so we see only the dark of his hair, crowned by a ring of laurels. The woman, with a halo of red hair surrounding her face, seems to collapse into his caress: her eyes are closed, one hand is languidly draped around his neck, the other hand reaches up to rest weakly atop the man’s own hand.

Regarded as his masterpiece, Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–08) (which he named The Lovers) was the shimmering pinnacle of the artist’s so-called “Golden Phase,” when ornamental gold leaf featured prominently in his canvases. (Touches of silver and platinum adorn the oil-on-canvas painting as well.)

As is often noted, Klimt’s flattened perspective and golden hues were partially inspired by the Byzantine frescoes he saw on two trips to Ravenna, Italy, in 1903. Japanese prints were another influence.

One of the most reproduced artworks of our time, The Kiss is emblazoned on coffee cups, magnets, posters in college dormitories—and even, in these strange times, on facemasks. The painting is so ubiquitous it is difficult to really see.

The picture, which hangs in the Upper Belvedere Museum in Vienna, is heroically scaled, measuring a perfect 72 inches square. Reproductions of the work often crop the painting to a more rectangular shape, obscuring the balanced heavenly realm Klimt had imagined the couple within.

And that’s just the beginning—the seemingly serene image is full of surprises. We’ve highlighted three intriguing facts that might change the way you look at it.

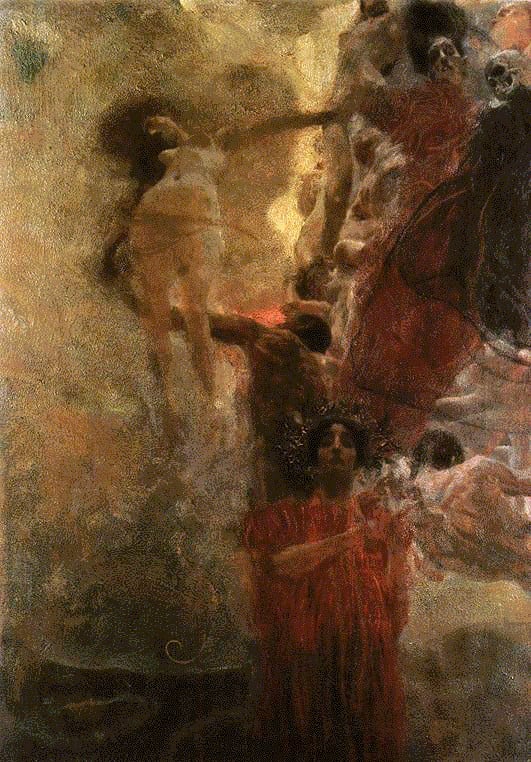

Gustav Klimt, Die Medizin (Kompositionsentwurf) (1897–98).

“All art is erotic,” Klimt once mused. That same philosophy occasionally got the artist into hot water. Klimt, who was notorious for his amorous proclivities (he is believed to have fathered some 14 children), emerged as a unique voice during a period of intense modernization in Vienna. At the dawn of the 20th century, long-standing Catholic traditions were upended by radical philosophies and the emerging field of psychology, including the writings of the city’s own Sigmund Freud.

Meanwhile, Vienna Secession artists like Klimt (and his admirers Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka) sought to fuse visions of the sacred and the profane, abandoning the formalities of academic styles, and embracing themes of desire, sexuality, and psychology, while freely incorporating elements of design.

But the outlandish Klimt was a bit chastened by the time he got around to painting The Kiss. Soon before he painted his masterpiece, he was commissioned to paint three works for the ceiling of the University of Vienna. As was typical of Klimt’s style, he painted female nudes as metaphors for philosophy, medicine, and jurisprudence. These paintings (which were subsequently destroyed by the S.S. during World War II) scandalized the public for their blatant depiction of pubic hair. Classified as pornographic, the paintings were to be removed when a startled Klimt called on a wealthy donor to help him retrieve the paintings.

In the months following, Klimt found himself doubting his artistic impulses. “Either I’m too old, or too nervous, or too stupid—there must be something wrong,” he wrote. Some believe that the relative restraint of The Kiss’s figures, with their fully clad bodies seemingly subsumed in giant decorative robes, may have been a reaction to the hubbub caused by the university paintings.

Luckily, the uproar did little to diminish the reputation of The Kiss; the painting was purchased by the city of Vienna before Klimt had even completed it for the then-astronomical price of 25,000 crowns.

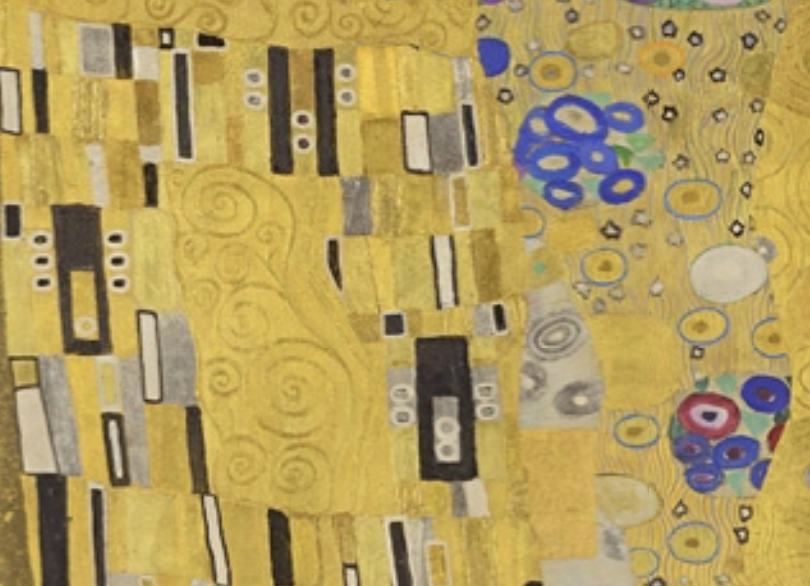

Detail from Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze (1902). Collection of the Vienna Secession Museum.

Though Klimt’s masterpiece doesn’t have the “perverted excess” his University of Vienna paintings were said to have, The Kiss still raised some eyebrows. Firstly, Klimt rarely depicted male figures, making The Kiss an interesting exception. Another is his 1901 Beethoven Frieze (on view at the Secession Building in Vienna), in which Klimt pictured comparably entwined male and female figures.

This earlier four-painting series provides a helpful frame for interpreting The Kiss. Centering on the human struggle for happiness, the Beethoven Frieze includes passages with monsters and poetry, and culminates in a picture of those comparable embracing figures. The catalogue for the Vienna Secession’s fourteenth exhibition described the painting as the depiction of the culminating choir of Beethoven’s symphony, saying: “Choir of angels from Paradise. Joy, lovely spark of heaven’s fire, this embrace for all the world.”

In this light, the embrace of the man and woman in The Kiss is a kind of transcendence of the earthly realm. This rather heady elevation was compounded by Klimt’s extensive use of gold leaf, which was historically reserved for religious subjects such as the saints in the Byzantine icons that inspired Klimt, leading some to think that Klimt’s Kiss was sacrilegious. (Klimt’s father had been an engraver and goldsmith, so the material had more intimate significance as well.)

Detail of The Kiss (1907–08).

And though the figures seem to dissolve beneath their intricate robes, the clothing may itself be suggestive. Art historian Patrick Bade has argued that Klimt’s ornamental elements can be interpreted as phallic and vaginal symbols: see the upright rectangular patterns on the man’s robe, and oval patterns on the woman’s dress. (What’s going on beneath these robes may be another story altogether.)

Regarding these interpretations, it’s worth noting that in addition to the fervor of psychoanalysis and its sexual implications, scientists were deeply engaged with studies of fertility during these years: in 1900, American scientist Miriam Menkin pioneered the process that would become in vitro fertilization.

George Frederic Watts, Orpheus and Eurydice. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

At the turn of the century, there was a certain stylistic vogue for archaic civilizations. As the art historian M.E. Warlick noted, Klimt may have been influenced by the work of Heinrich Schliemann, “whose excavations of early Greek civilizations were widely publicized.”

“Artifacts from archaic civilizations were being collected avidly in German and Austrian museums,” Warlick added.

Detail of The Kiss (1907–08).

Though Klimt’s fascination with ancient Greece and Egypt may be more stylistically pronounced in works like Pallas Athenae and the Tree of Life, some historians have suggested that The Kiss may be Klimt’s vision of the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

In the story, a lovelorn Orpheus travels to the underworld to rescue his departed wife, Eurydice. Hades, lured by Orpheus’s lyre, agrees to release her, but only on the condition that Orpheus does not turn to look at her before they exit the underworld. Steps from their final escape, Orpheus tries to steal a glance at his beloved, concerned that she may not be there. She is—but suddenly, she vanishes.

The tale was certainly popular among artists of the age. The painter Oskar Kokoschka wrote a play based on it a decade after Klimt painted The Kiss, and Symbolist painters like Maurice Denis would take it as subject matter. If correct, then, rather than swooning in the arms of her lover, the woman pictured here may be withering into fantastic nothingness.