Cuban authorities released artist Hamlet Lavastida on Saturday after three months of detention at Villa Marista, the state security headquarters. He and his partner, the poet Katherine Bisquet, were escorted by 20 agents directly to José Martí Airport and flown to Poland without a chance to bid their families farewell. The couple’s dramatic exit put an end to a 90-day ordeal, during which, Lavastida said, “my work became my life.”

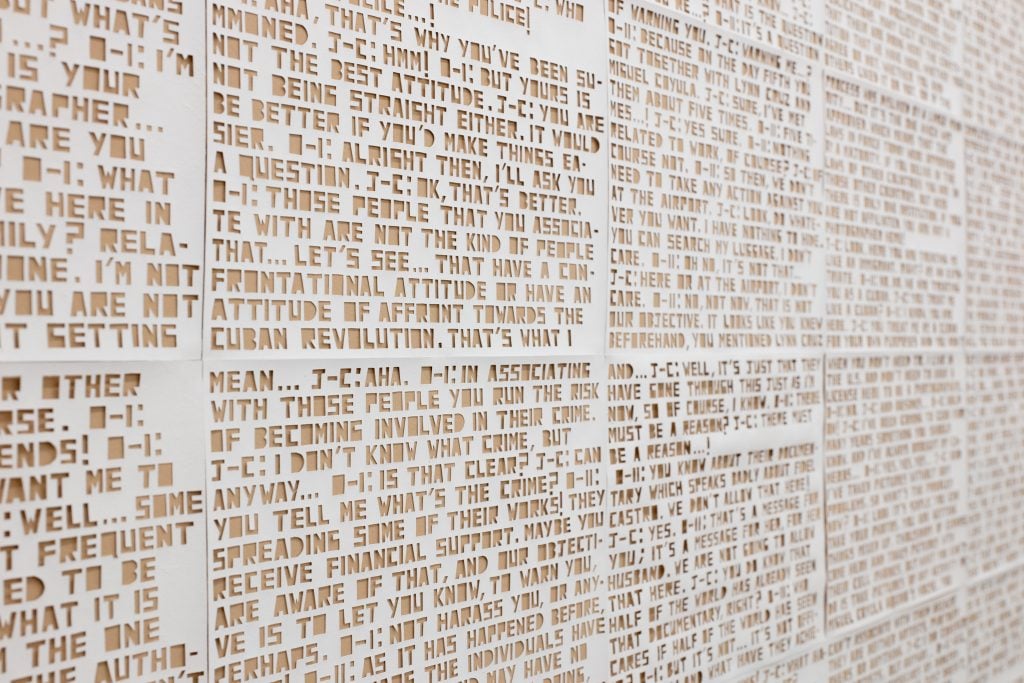

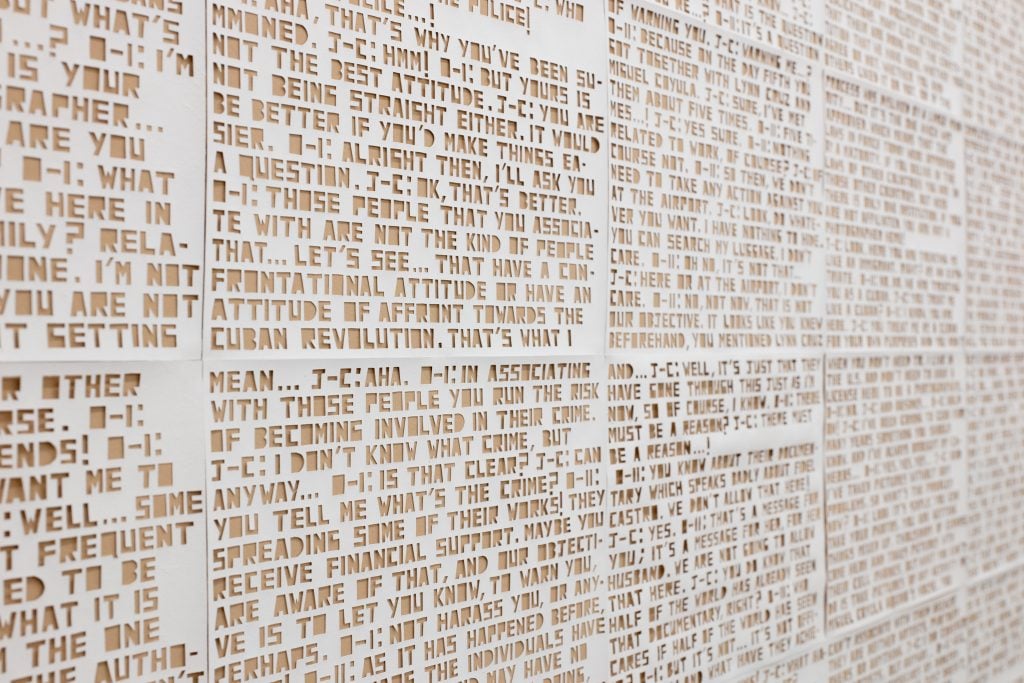

Lavastida has devoted his entire artistic career to the investigation of Cuban revolutionary state rhetoric and propagandistic graphics. In his latest exhibition, which he created during his residency at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin in April, he juxtaposed transcripts of a police interrogation and a forced confession by a Cuban poet with a mosaic of imagery related to the Cuban security apparatus.

He returned to his homeland on June 20 and spent six days in mandatory quarantine before being arrested. During daily interrogations, he learned that he was accused of “instigating to commit a crime” because of an idea that he had shared with the art-activist group 27N in a private chat. The proposal that supposedly constituted an offense consisted of stamping Cuban currency with the logos of two activist groups; the work was not realized.

Once mass protests broke out across Cuba on July 11, Lavastida’s interrogators escalated their threats, suggesting that he could be tried for “instigating rebellion,” which carries a 15- to 20-year sentence, alleging that he had returned to the island to lead the uprising.

A group of young intellectuals and artists demonstrate at the doors of the Ministry of Culture during a protest in Havana, on November 27, 2020. Photo by Yamil Lage/AFP via Getty Images.

Speaking from Warsaw this week, Lavastida explained that his interrogators, euphemistically called “instructors,” tried to force him to confess, first to having taken orders from the U.S. State Department, and then to being managed by secret agents in Poland, where he resided between 2012 and 2015 and has a son.

He noted that political prisoners are routinely given three choices that they are told will ensure favorable treatment: to incriminate themselves by pleading guilty to charges, to denounce others also responsible for the charges, or to repent.

The agents at Villa Marista dictate how such statements are to be formulated and maintain the prerogative of using those documents to absolve the state of any wrongdoing.

“Inside that world, I could see that even though the economy is in shambles and Cuban people are suffering extreme poverty, the Cuban police state remains all powerful and has access to all the resources it needs,” he said.

Recognizing that Cuban State Security superseded any judicial authority, which led him to believe he would never have a fair trial, Lavastida opted for repentance as the least offensive of the three options. By September, he said, the authorities ceased the constant interrogations and instead sought to use the promise of his release to force Bisquet to accept exile for them both.

A detail view of Hamlet Lavastida’s project “Cultura Profiláctica” on view at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. Photo: David Brandt. Courtesy of the artist.

Lavastida was held in a small prison on the top floor of the security headquarters along with dozens of others accused of political crimes. He said he shared a tiny cell with three other inmates, had minimal phone contact with his mother and partner, and was allowed out for sunshine on a rooftop patio four times during his imprisonment. Meals were meager, books were scarce, and the only media available was state television news that was blasted in the prison hallway several times a day, he recounted. “I saw other prisoners losing their minds and at a certain point I started to experience hallucinations—I heard voices,” he said.

In early September, he contracted COVID-19 and was removed to a prison infirmary for several days. After that, preparation for his departure began and he was transported to a safe house with his head between his legs. Although plans had been made for him to return to Germany with Bisquet, the Cuban government decided against it in order to avoid the appearance of forced exile; they wanted, Lavastida said, for him to fly to Poland so they could claim that he was leaving to be reunited with his son.

Cuban authorities agreed to extend his passport for two years but sent him off with a warning: If he continued to criticize the government and tried to return, “Villa Marista would await” him.