Art & Exhibitions

Harry Clarke’s Beloved and Controversial Stained Glass Window Returns to the Wolfsonian in Miami Beach

The window was meant as a gift to the League of Nations—until the Irish government censored it.

The window was meant as a gift to the League of Nations—until the Irish government censored it.

Sarah Cascone

A beloved piece of Irish history—both beautiful and scandalous—is back in the spotlight in Miami Beach this year, on view in “Harry Clarke and the Geneva Window” at the Wolfsonian FIU.

The work is a luminous stained glass window by Harry Clarke (1891–1931), commissioned by the Irish Free State in 1926 for the International Labor Court at the League of Nations building in Geneva.

The show at the Wolfsonian juxtaposes the jewel-like window with late 19th and early 20th-century Irish decorative artworks. It also delves into the controversy surrounding the piece, as well as Clarke’s life and career, which was tragically cut short by his premature death at the age of just 41.

Battling ill health from tuberculosis and juggling multiple projects, Clarke finally finished the Geneva Window in May 1930. By the following January, he was dead—and so too was the commission.

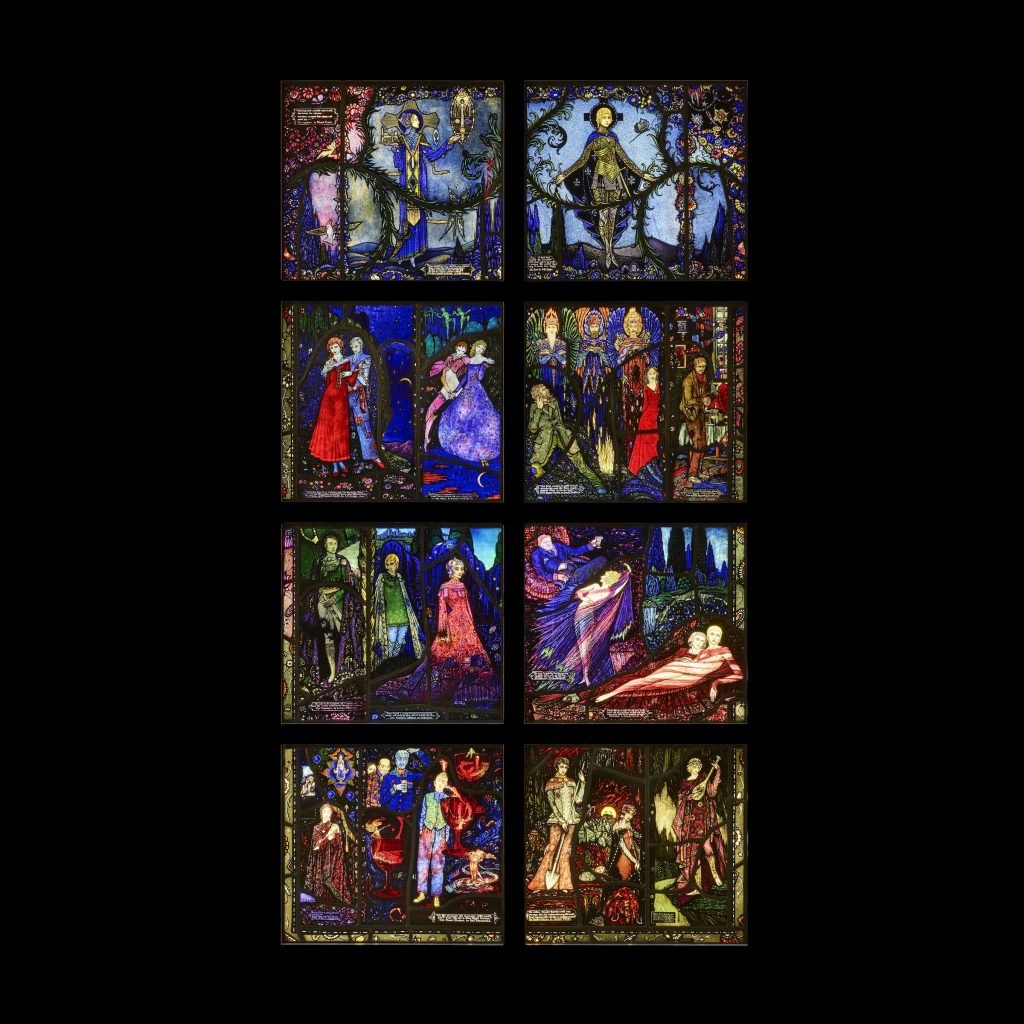

Harry Clarke, Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

The Geneva Window is one of the artist’s greatest masterpieces, but the Irish government ultimately rejected the window due to its shocking content, including drunkenness, nudity, and—perhaps worst of all—Protestants.

“Ireland was incredibly conservative at this moment in time,” exhibition curator Lea Nickless told me, admitting that Clarke probably should have known that the work would not be well received.

The nation had just won its independence from Great Britain five years prior, in 1921. Clarke, for his part, was greatly influenced by the turbulent moment at which he came of age, characterized by nationalism and the Celtic Revival, which sought to craft a modern Irish identity informed by its ancient history and the Gaelic language.

Harry Clarke, The Demi-Gods by James Stephens and Juno and the Paycock by Sean O’Casey from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

The Geneva Window was meant to be a reflection of Irish culture. But in the contract for the commission, the artist remained vague about his vision for the window, saying only that he would highlight the modern Irish writer with “opportunities for phantasy.”

“At that moment in time, Irish literature was really at the apex of Irish cultural output,” Nickless said, noting that the Irish Literary Revival was closely tied to the country’s nationalist movement.

Harry Clarke, The Wayfarer by Patrick (Pádraig) Pearse and The Story Brought by Brigit by Lady Gregory from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

One of the Geneva Window panes honors Patrick Pearse, a poet and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916. The rebellion failed, and Clarke even lost his illustrations for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner in a fire that broke out during the uprising. He commemorated the conflict in the Geneva Window by including a poem Pearse wrote the night before his execution by the British.

But of the 15 writers Clarke chose to highlight in the commission—George Bernard Shaw, James Stephens, Sean O’Casey, Liam O’Flaherty, George William “Æ” Russell, Seumas O’Kelly, James Joyce, George Fitzmaurice, Padraic Colum, Lennox Robinson, William Butler Yeats, Seamus O’Sullivan, John Millington Synge, Lady Gregory, and Pearse—seven were Protestant. That was a problem, considering the nascent country’s staunch Catholicism.

Harry Clarke, The Playboy of the Western World by John Millington Synge and The Others by Seumas O’Sullivan from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

And some of the window panes were considered too provocative, like the depiction of the titular character from Synge’s popular 1907 play Playboy of the Western World, with tight breeches highlighting his manhood in an erotic manner. In the same pane, another male character from a Seumas O’Sullivan poem seems to place a woman’s hand over his crotch. Several of the featured literary scenes prominently included alcohol consumption, which was not the image of Ireland that its leaders wished to present to the world.

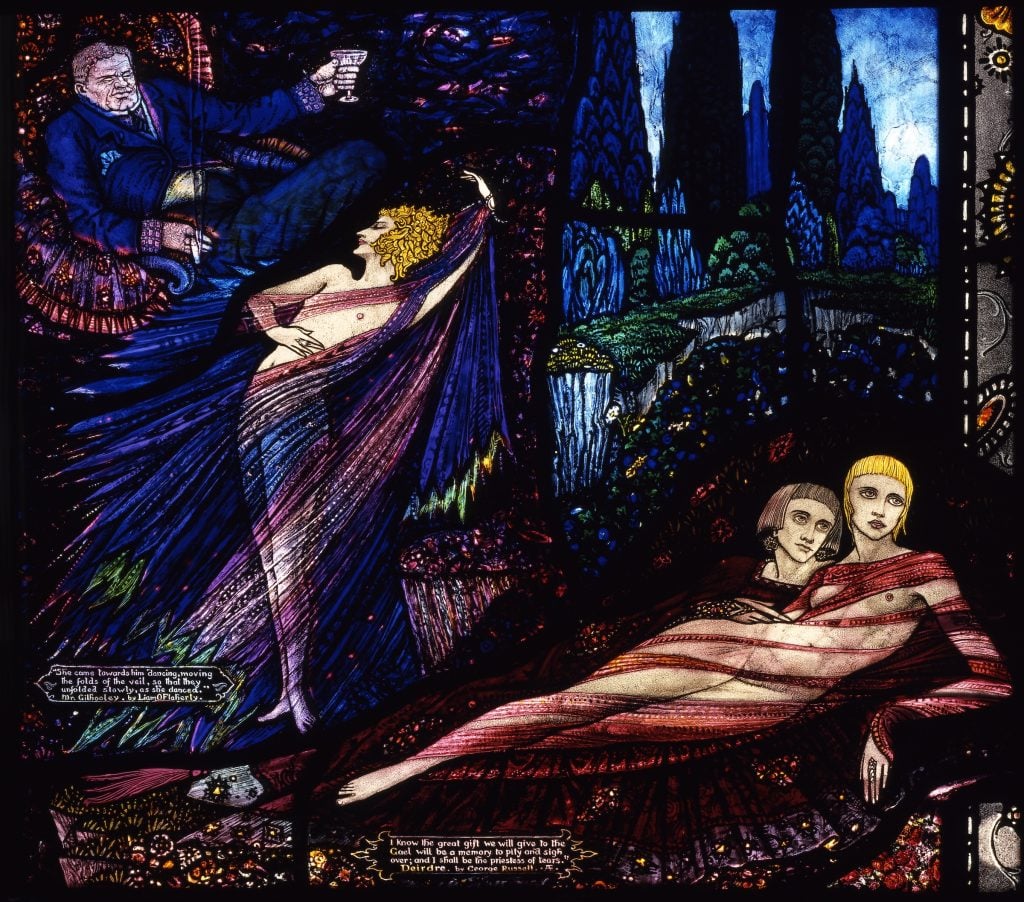

And then there was the pane taken from the 1926 novel Mr. Gilhooley, where a woman clad in a gauzy gown revealing her naked bosom dances for a middle-aged man. The author, O’Flaherty, had actually had work banned under Irish law, as had Joyce, for immorality.

Harry Clarke, Mr. Gilhooley by Liam O’Flaherty from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

After the window’s completion, a government official warned Clarke that showcasing Protestants as Irish representatives “would give grave offence to many of our people.” The window was “beautiful,” but the other elements of the work deemed problematic “would give rise to misunderstanding and much adverse comment.”

In the end, the risk of public controversy was just too great, and Ireland never gifted the Geneva Window to the League of Nations. Clarke’s widow, the artist Margaret Clarke (1881–1961), bought the painting back from the government in 1932.

Though Clarke may not be a household name in the U.S., he is a key figure in Irish art history.

Harry Clarke, The Weaver’s Grave by Seumas O’Kelly from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

“In Ireland, Harry Clarke is considered the greatest artist of the 20th century—and forget stained glass, that’s across the board,” Nickless said. “He is incredibly venerated.”

Born on St. Patrick’s Day, Clarke trained in stained glass from the age of 14, apprenticing at his father’s church decorating firm in Dublin. He actually first achieved renown as an illustrator, creating drawings for widely disseminated works such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust. (One of those drawings, featuring a self portrait of the artist with Mephistopheles, is part of the Wolfsonian show.)

But when Clarke began focusing on glass, he was doing things with the medium that no one else could do, achieving painterly effects with rich color and fine details. He used acid etching on “flashed” glass that is clear on one side and layered on on the other. Clarke would dip the glass in wax, and then scrape parts of the wax away before immersing the glass in hydrofluoric acid, creating subtle gradations in color where the wax had been removed.

Harry Clarke, A Cradle Song by Padraic Colum from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

“He was known to go through the process sometimes as many as six times for each piece,” Nickless said. “Working with this acid bath, he was right on top of these vats of acid, breathing that in for years on end. It definitely contributed to his ill health and to his tuberculosis and his lung problems.” (Clarke checked in to a Swiss sanatorium for treatment in 1929 and again in 1930, dying on his journey home.)

The Geneva Window is something of his magnum opus. The majority of Clarke’s other stained glass works were done for the Catholic church. Though it was ultimately censored, the Geneva Window gave him a unique artistic freedom.

“This was the true Harry Clarke expressing himself,” Nickless said. “And this was an opportunity to create a modern identity for Ireland. So that’s what he was so excited about.… and just the way he’s done it is not like any other stained glass artist that you see.”

Harry Clarke, The Dreamers by Lennox Robinson and The Countess Cathleen by W.B. Yeats from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

Though it might seem strange that one of Ireland’s most important 20th-century treasures landed in Florida, Margaret Clarke was so upset by the government’s censorship of the work that she vowed it would never go to an Irish museum.

When Wolfsonian founder Mitchell “Micky” Wolfson Jr. was amassing his collection, which focuses on the years 1850 to 1950, he worked closely with the Fine Art Society, a gallery in London. The dealer helped arrange a loan of the window for an exhibition Wolfson held in Miami in 1982.

Then, after a 1988 show of the artist’s work at the gallery, Clarke’s sons agreed to sell Wolfson the work. (The price was in excess of £100,000 [$178,000], according to a London Times article at the time.)

For 25 years, the Geneva Window was the star of the show at the Wolfsonian, which opened in 1995. It became part of Florida International University when Wolfson donated its collection and Miami Beach building to the state of Florida. But when the museum deinstalled its permanent collection galleries for a renovation project in 2020, the window went into storage.

Harry Clarke, St. Joan by George Bernard Shaw from Harry Clarke Geneva Window (1926–30). Collection of the Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, the Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection.

“We would get the most heartbreaking emails and calls from Irish people who said ‘we travelled all the way to Miami to see the Harry Clarke window, but it had been taken down,'” Nickless said. “We realized we had to put it back up!”

The museum intends to keep the current exhibition on view indefinitely. But when the time comes to rotate the collection’s display, the Geneva Window won’t be going anywhere.

“On the surface, it is a spectacularly luminous, incredible piece just to look at. It’s beautiful,” Nickless said. “But then it has all of these other stories. The literary stories of each of these 15 writers, but also the narrative of Irish resilience and Ireland’s striving to become its own independent nation. So it’s one of those complicated works to really figure out and understand. That’s what makes it even more fascinating.”

“Harry Clarke and the Geneva Window” is on view a the Wolfsonian–FIU, 1001 Washington Avenue, Miami Beach.