Law & Politics

Harvard Can Keep Daguerreotypes Depicting Enslaved Africans, Despite Objections From One of the Subject’s Ancestors, a Court Has Ruled

The photos belonged to the photographer, not the subjects, the judge ruled.

The photos belonged to the photographer, not the subjects, the judge ruled.

Taylor Dafoe

Harvard University does not have to hand over a set of 19th-century daguerreotypes, thought to be among the first photographs of enslaved people in America, to one of the subject’s ancestors, a Massachusetts judge has ruled.

In dismissing the case, the judge has ended one chapter of the lawsuit, which began in March 2019 when a retired probation officer in Connecticut named Tamara Lanier filed a lawsuit alleged that the Ivy League university illegally owned the photos and was responsible for a “decades-long campaign to sanitize the history of the images and exploit them for prestige and profit.”

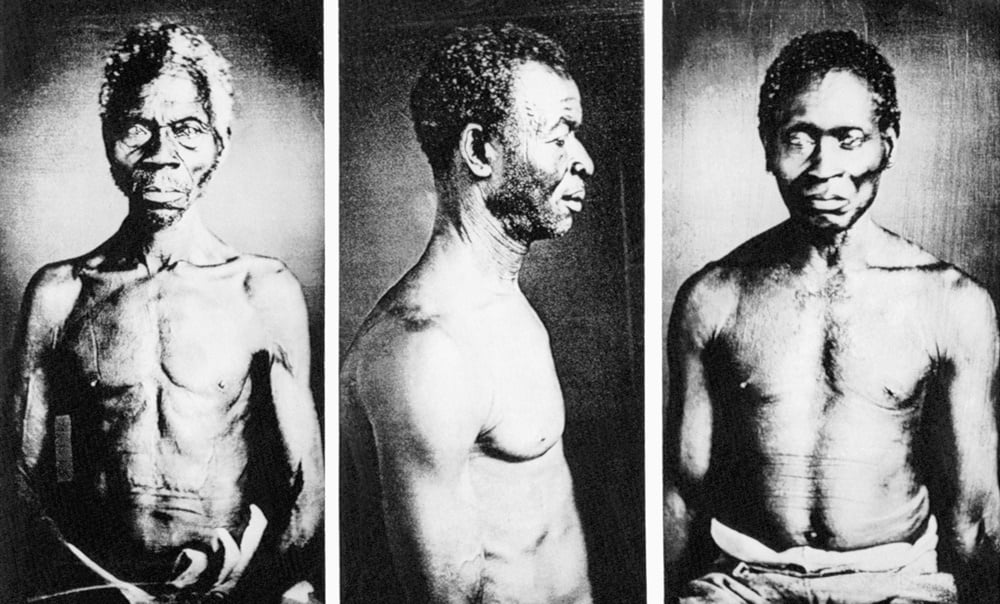

The case drew instant headlines at the time for the tricky ethical questions at its core. The photos, taken in 1850, were commissioned by Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz and used as evidence to support his theory that Black people were biologically inferior to white people. They depict a man named Renty and his daughter, Delia, from the waist up. Per Agassiz’s orders, the two were “stripped naked and forced to pose,” according to the lawsuit, “without consent, dignity, or compensation.”

Yet, despite the “horrific circumstances” into which the images were born, according to the judge’s ruling this week, Lanier has no legal right to the photos, which belong to the photographer, not the subject.

“Fully acknowledging the continuing impact slavery has had in the United States, the law, as it currently stands, does not confer a property interest to the subject of a photograph regardless of how objectionable the photograph’s origins may be,” wrote Middlesex superior court judge Camille Sarrouf. The university also will not have to pay Lanier damages, per the ruling.

Photos discovered in the basement of a Harvard University museum. Among the previously unpublished daguerreotypes discovered are these (L-R): a Congo slave named Renty, who lived on B.F. Taylor’s plantation, “Edgehill”; Jack, a slave from the Guinea Coast (ritual scars decorate his cheek); and an unidentified man.

Sarrouf ruled against Lanier’s assertion that Harvard’s treatment of the photographs constituted a violation of her civil rights, which fell beyond the three-year statute of limitations governing such claims. The right to control the commercial usage of the photos lapsed with the death of the subjects, the judge said.

Lanier’s attorney, Ben Crump, said in a statement that he remains “convinced of the correctness of Ms. Lanier’s claim to these images of her slave ancestors and that she will be on the right side of history when this case is finally settled.”

“It is past time for Harvard to atone for its past ties to slavery and white supremacy research and stop profiting from slave images,” the lawyer added.

Harvard did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Lanier has said that she plans to appeal the ruling. The judge, she told the New York Times, “completely missed the humanistic aspect of this, where we’re talking about the patriarch of a family, a subject of bedtime stories, whose legacy is still denied to these people.”

The daguerreotypes were rediscovered in a box at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in 1976. Despite growing up with stories about “Papa Renty,” Lanier did not know the photos of her great-great-great-grandfather existed until 2010, when she charted her genealogy.