Law & Politics

‘Morally, Harvard Has No Grounds’: Inside the Explosive Lawsuit That Accuses the University of Profiting From Images of Slavery

We asked legal experts and art historians to weigh in on the groundbreaking lawsuit.

We asked legal experts and art historians to weigh in on the groundbreaking lawsuit.

Eileen Kinsella

A thorny lawsuit making its way through the courts pits Harvard University against a woman who claims she is the direct descendant of slaves depicted in several 19th-century daguerreotypes owned by the school’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

In a case filed on March 20 in a Massachusetts court, Tamara Lanier is asking for Harvard to hand over the daguerreotypes, which were first rediscovered in a box at the Peabody Museum in 1976, and to pay damages and “other legal and equitable redress” to be determined by a jury. According to the lawsuit, Harvard has been behind a “decades-long campaign to sanitize the history of the images and exploit them for prestige and profit.” No monetary amount or estimation of the school’s profit is cited.

The case has already sparked intense debate and raises complicated legal and ethical questions about the ownership of cultural property, particularly against the backdrop of the United States’s long and shameful history of slavery.

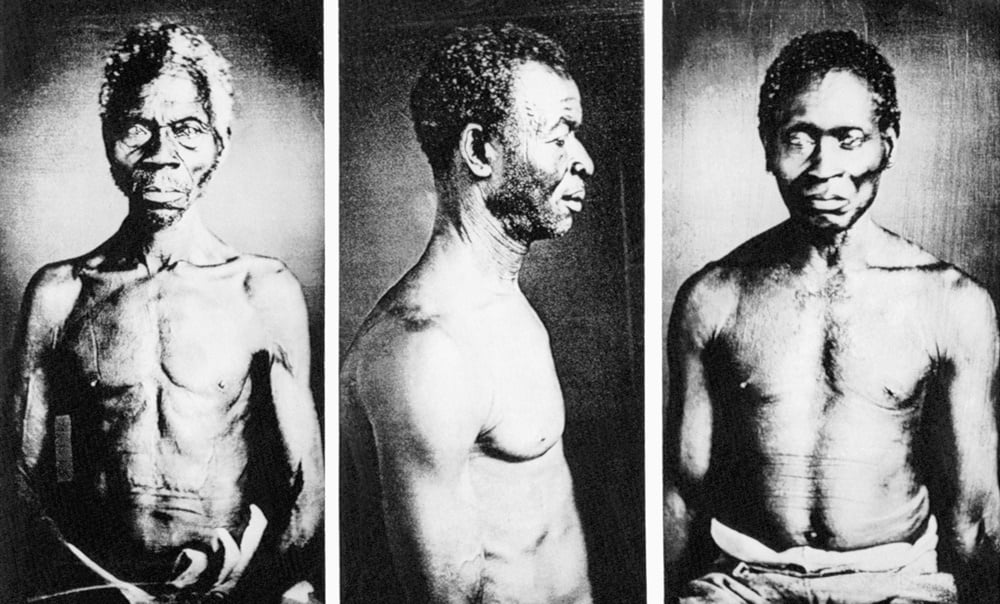

The pictures have a sordid history. They were made at the behest of Louis Agassiz, a Swiss researcher and one of Harvard’s leading scientists, as part of his quest to “prove” black people’s “inherent biological inferiority and thereby justify their subjugation, exploitation, and segregation,” according to Lanier’s suit.

The subjects of the 1850 daguerrotypes are a man known as Renty and his daughter, Delia, both of whom were enslaved in South Carolina. At Agassiz’s orders, Renty and Delia were “stripped naked and forced to pose… without consent, dignity, or compensation,” according to the lawsuit. Lanier says Harvard is squarely to blame for the situation, since it elevated Agassiz to the highest echelons of academia and steadfastly supported him as he sought to legitimize the myth of white superiority.

“Seeing those images over and over again out in the world is damaging,” says Jessie Morgan-Owens, a professor at Bard Early College in New Orleans. “These images inculcate racism—that’s what they are for.”

The university has yet to publicly comment on the lawsuit and did not respond to artnet News’s request for comment.

An image of Renty, on the far left, was among those discovered the the Peabody Museum at Harvard university in 1976. Photo: Getty Images.

The lawsuit is a legal and ethical minefield. Should Harvard hand over the daguerreotypes, as Lanier had been requesting for years prior to filing the suit? Do the pictures serve as a reminder of a heinous history and thus require institutional context? Or do they simply reify the abhorrent policies they were created to justify in the first place?

artnet News asked a bevy of lawyers and art historians to weigh in on this complicated case. There’s one thing they all agreed on: that this unprecedented lawsuit raises far more questions than it answers.

“Legally, what seems to me to be the most compelling issue is, which law will the courts apply?” asked art lawyer Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. “Will they apply the laws of 1850, or will they apply current law?”

Further complicating matters is the fact that typically, enslaved people were unable to legally own property or images of themselves unless their owners allowed it, says Brenda Stevenson, Nickoll Family Endowed Chair in History at UCLA.

“Even then, an enslaved person’s ‘property’ could be contested by one of their owner’s legal heirs, unless a slave’s right to own this property was very particularly protected by legal documentation that could hold up in court,” she says.

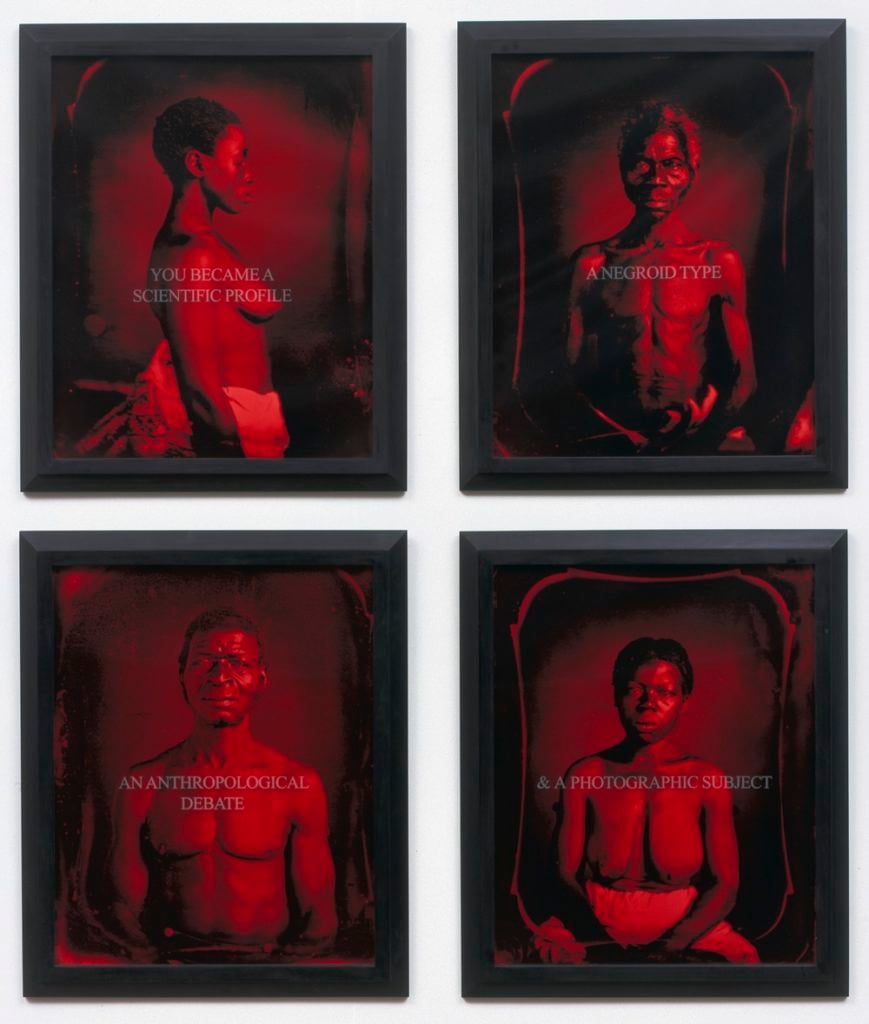

Carrie Mae Weems The Peabody Quad from the series, “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.” (1995-96) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

But the lawsuit also throws light on more recent legal history. In the 1990s, artist Carrie Mae Weems used Agassiz’s images of Renty and Delia in her series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. Though she initially signed a contract with Harvard promising not to use the images without permission, she later rescinded, photographing the pictures and putting them into her work. When Harvard threatened legal action, Weems shot back: “I think that your suing me would be a really good thing. You should. And we should have this conversation in court.” Harvard eventually backed off.

“I’ve known about the case for some time, and of course, I too have a long history with these images,” Weems told artnet News in an email. “It’s wonderful that the varying stories are finally emerging after so many years,” she says.

But in Lanier’s suit, she claims that the university then “expanded its dominion over the daguerrotypes by purchasing Weems’ collection for its own museum.” Harvard did not respond to artnet News’s questions about the acquisition.

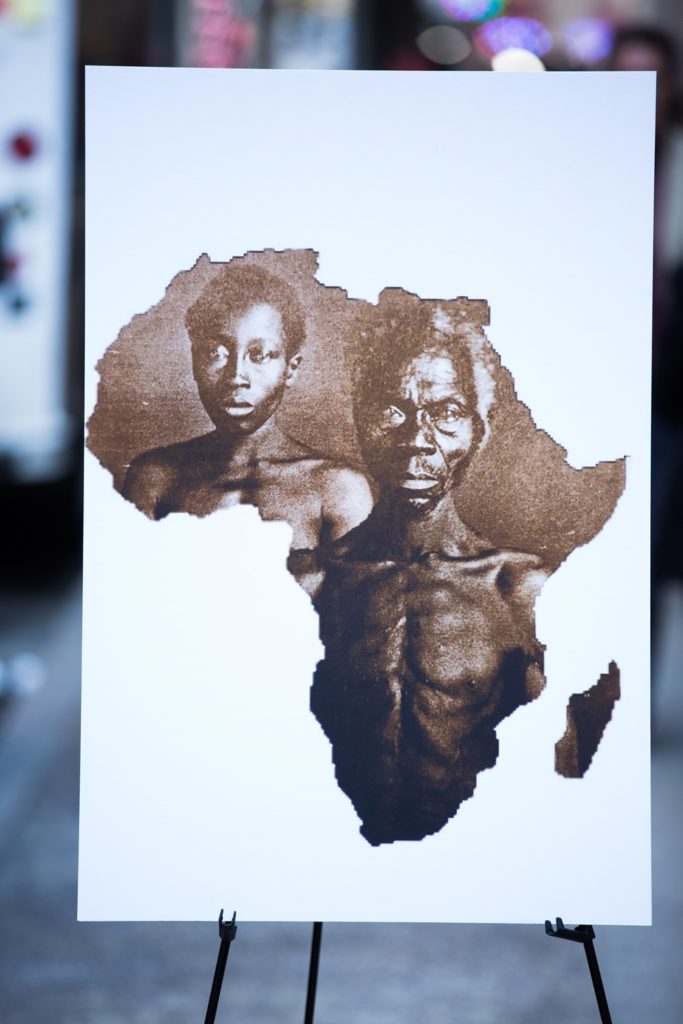

A sample image of Renty and his daughter, Delia, presented during a press conference announcing the lawsuit against Harvard University. Photo by Kevin Hagen/Getty Images.

Then there are deeper problems, which the case inevitably brings to the fore. “Morally, the courts will be faced with the question of whether to seek and find equitable outcome,” Sarmiento says. “In other words, what [does] the court thinks is the ‘right’ outcome? Based on the current legal record, it does seem like there was misappropriation by Louis Agassiz and a huge and ongoing benefit to the University.”

“My initial reaction is that I’m sorry this case is in a court, which is an adversarial proceeding in which one party must win and one party must lose,” Stephen K. Urice, a professor of law at the University of Miami School of Law, told artnet News. “The ethical issues are profound and really need frank discussion. I would have been much happier to see if the plaintiffs and her attorneys could have opened Harvard to a broader dialogue, though it seems Harvard wasn’t open to that.”

But other institutions have already been making headway in involving the descendants of slaves in their missions. James Madison’s Montpelier, the plantation home of the fourth US president, has a volunteer archaeology program in which descendants can help recover artifacts, says Jennifer Van Horn, professor of art history and history at the University of Delaware. “I think that we can take a cue from plantation museums like James Madison’s Montpelier.”

Still, the question remains: what will Harvard do?

“Morally, Harvard has no grounds to withhold the return of these images to a family member,” Stevenson says. “France has decided to return art stolen from Africa during its colonial domination of parts of that continent. Other European countries have done so—to a limited extent—in the past. Why shouldn’t African Americans be able to claim images of their ancestors when these images were taken under force of punishment? These reparations need to be made.”