Analysis

Hauser and Wirth Opens Huge Philip Guston Show Pinpointing ‘Pivotal’ Decade

You can look, but you can't buy.

You can look, but you can't buy.

Eileen Kinsella

Roughly eight months after taking over representation of the Philip Guston estate, mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth has opened a huge new show of the artist’s work at its cavernous space in Chelsea.

“Philip Guston: Painter 1957—1967,” opened April 26 and runs through July 29. It features 36 paintings and 53 drawings that show the artist’s exuberant embrace of Abstract Expressionism.

The bulk of the works are on loan from private collections and from museums (The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the High Museum in Atlanta, the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, and Kunstmuseum Winterthur are among them). This means that the show is atypical for a gallery affair: just a handful of works in the show are actually available for sale.

Paul Schimmel with the artist’s daughter, Musa Mayer, and Marc Payot at the Hauser and Wirth preview of “Philip Guston: Painter, 1957–1967.” Courtesy of Eileen Kinsella.

On hand for the crowded press preview on Tuesday were Hauser and Wirth partner and director of the gallery’s newly opened Los Angeles branch, Paul Schimmel, partner and vice president Marc Payot, and Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, whose acclaimed 1988 book Night Studio, a memoir about her father, is being republished by the gallery this month.

“I would telephone Western Union with all kinds of lies, such as that my teeth were falling out, or that I was sick. It was such a relief not to have anything to do with modern art,” Mayer quotes her father saying after he brought the family to Woodstock to live, away from the art openings of his Abstract Expressionist friends.

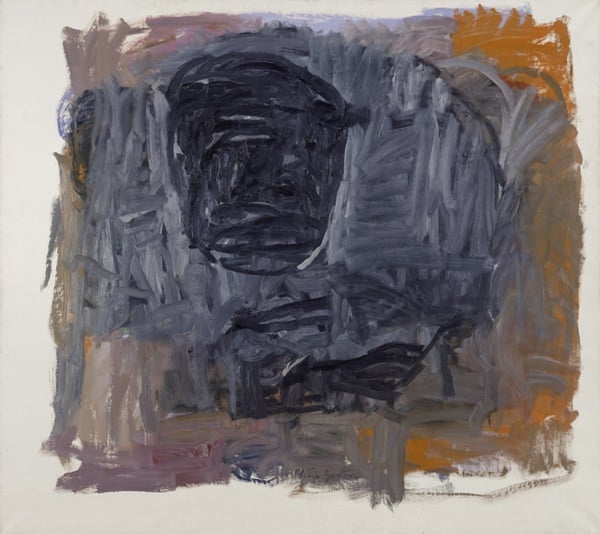

Philip Guston Painter III 1963. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Payot kicked things off by noting that this is the first time in 50 years a body of Guston abstract paintings and drawings as extensive as this has been exhibited together.

Schimmel, who led a walk-through of the tour while discussing Guston’s process as a painter noted that “for some decades now, this has been described as a transition period” but he argues that it is much more transformative than previously thought.

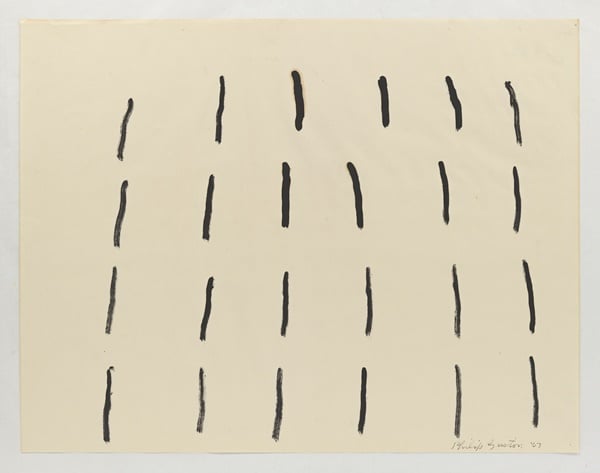

Philip Guston Untitled (1967). ©The Philip Guston Estate. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

There seems to be no doubt that the art world—especially as reflected in Guston’s market—has ever done anything but fully embrace and applaud the artist’s output from this period, so the defense is an odd one. It’s also no secret that it directly preceded Guston’s eventual shift back to figuration with wildly-colored, cartoonish figures which turned off fans and critics alike at the time, not to mention that it horrified younger AbEx artists like Joan Mitchell and Cy Twombly, who saw the change in style as a betrayal.

While the works are gorgeous, and wonderful to see together in this context—with their visible stylistic shifts—they are hardly surprising, despite the gallery’s claims.

Schimmel talked at length about Guston’s history, process as a painter, and broader oeuvre, including some of the internal contradictions he was apparently grappling with during his career.

“He was, as he described it, resistant of forms losing their identities between painting abstraction and in representation, self representation of the sort he was seeking, as he described, as almost a state of inertia. He needed to create more solid forms, and that sense, the creation of these forms, is really the subject of this entire exhibition. In a way, to see through the trajectory of this show, he begins with this search for more solid forms and his concern that the loss of the object, whether it’s a still life or a person, was catastrophic for abstraction and the New York School.”

Perhaps an easier-to-absorb takeaway from the show is Guston’s refusal to let critical and commercial success dictate his style or pursuits.

The show ends with a series of “Pure Drawings”—executed during a time when the artist abandoned painting altogether—that presage the rough, primitive-style markings that announced the later figurative works.

Philip Guston Alchemist (1960). ©Philip Guston Estate. Courtesy of Hauser and Wirth.

Guston “had this ability to kind of push back on his own history, on both the critical and commercial success that he had achieved,” said Schimmel.

According to the artnet Price Database, seven of the ten highest lots of Guston’s work at auction are for abstract works. The record, of $25.8 million, was set at Christie’s New York in May 2013, for To Fellini (1958), which was estimated at $8 million to $12 million.

The record for his figurative work is $6.5 million, for Head and Bottle (1975), set at Christie’s New York in May 2007. Not bad for an artist searching for “solid forms.”