Travel

Here Are 8 Mythic Artist Studios to Visit Across America, From Georgia O’Keeffe’s Desert Retreat to Winslow Homer’s Ocean-Sprayed Bungalow

Some ideas for your next cross-country roadtrip.

Some ideas for your next cross-country roadtrip.

Annikka Olsen

Appreciating an important work of art in a museum or gallery is one thing, but what if you want to go deeper and understand the artist too? Seeing where they worked, and often lived as well, can offer incomparable insight into their life, practice, and the masterworks they produced. Thankfully, many artists’ homes and studios across the country have been kept intact and opened to the public, allowing art lovers and history buffs alike to step back in time to see how some of art history’s most famous artists worked.

We’ve gathered here eight historical artists with studios in the U.S. that have been preserved, so you can visit on your next road trip.

Exterior of 101 Spring Street. Photo: Joshua White. Courtesy of the Judd Foundation.

An incredibly influential postwar artist, art critic, and pioneer of Minimalism, Donald Judd (1928–94) had a wide-ranging vision, with a practice that stretched from sculpture and painting to furniture design and writing. In 1968, Judd purchased a five-story building at 101 Spring Street, which he used as a residence and studio, and was the site where Judd first developed the idea of a permanent installation. In the early 1970s, Judd also began spending time in Marfa, Texas, eventually purchasing several buildings and a significant amount of land, which ultimately became another residence, studios, and the basis for the Chinati Foundation.

Together, both 101 Spring Street and the Marfa spaces compose one of the most expansive and comprehensively preserved artist studios, residences, and museums today, all of which are part of the Judd Foundation. Whether visiting the Soho building or the Block—a building complex comprised of a residence, studios, library, and galleries in Marfa (both require advance reservations)—visitors can get a glimpse into the milieu that Judd’s inimitable oeuvre was produced.

View of the courtyard inside the Block. Photo: Mathew Millman. Courtesy of the Judd Foundation.

The studio where Jackson Pollock painted from 1946–56 and was later used by Lee Krasner from 1957–84. Courtesy of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

Jackson Pollock (1912–56) is considered one of the most important American artists of the 20th century alongside his wife, Lee Krasner (1908–1984). The couple moved to the town of East Hampton, New York, in 1945 for a fresh start away from the hubbub of New York City. Initially, Pollock used one of the home’s bedrooms as a studio but began working instead in an outbuilding on the property—where he would go on to paint some of his most famous works.

Following Pollock’s death, Krasner began using the space as her own studio. When Krasner died, ownership of the property went to the Stony Brook Foundation, administered by Stony Brook University. Conservators were able to tend to the home and studio—even discovering Pollock’s paint splatters under the Masonite flooring that was later installed—and it was transformed into the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. Open from May through October, admission is by guided tour only and reservations are required.

The Norman Rockwell Museum and Studio, Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Photo: by: John Greim/Loop Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

There is perhaps no other artist who is so closely associated with Americana than Norman Rockwell (1894–1978). His iconic paintings of American life—albeit highly idealized—led him to colloquially be known as the “storyteller of America,” and one of the most famous artists of all time. Originally from New York City, in 1953 Rockwell and his family settled in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life.

In 1969, aided by Rockwell himself and his wife Molly, the Norman Rockwell Museum was founded in Stockbridge near the couple’s home, and was dedicated to “the enjoyment and study of Rockwell’s work and his contributions to society, popular culture, and social commentary.” In 1986, the studio building he used at his home was cut in two and moved, along with its contents, to the museum. It can be visited between May and October.

The Winslow Homer original studio on Prouts Neck, Portland Museum of Art. Photo: Gordon Chibroski/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images.

American painter Winslow Homer (1836–1910) initially worked as a commercial illustrator before he began experimenting with oil paints in the early 1860s. Largely self-taught, Homer garnered a reputation for his captivating landscapes, particularly those involving marine subject matter, leading him to become one of the most celebrated painters of the 19th century.

Hailing from Boston, Homer relocated to Scarborough, Maine, in the 1880s, seeking rural solitude and taking inspiration from the natural landscape. Homer’s home and studio fell into relative obscurity following his death, but in 2006 the Portland Museum of Art purchased the property and spent six years renovating and restoring the building. In 2012, the studio opened its doors to the public for the first time, allowing visitors to discover the landscape that was central to the artist’s work.

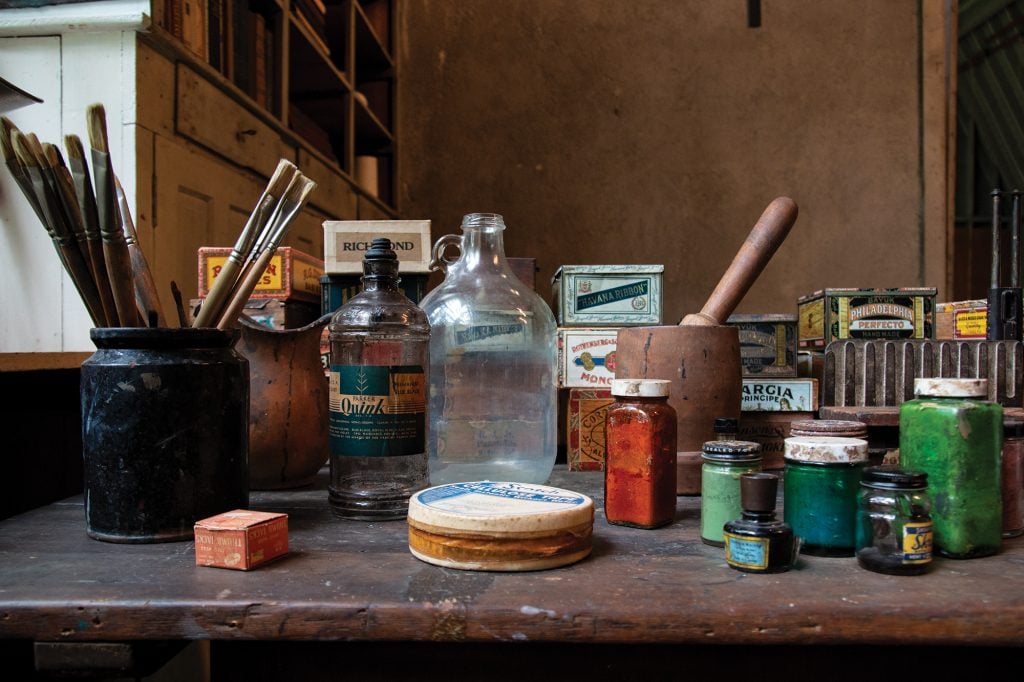

N.C. Wyeth Studio, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Photo: Daniel Jackson. Courtesy of the Brandywine Museum of Art.

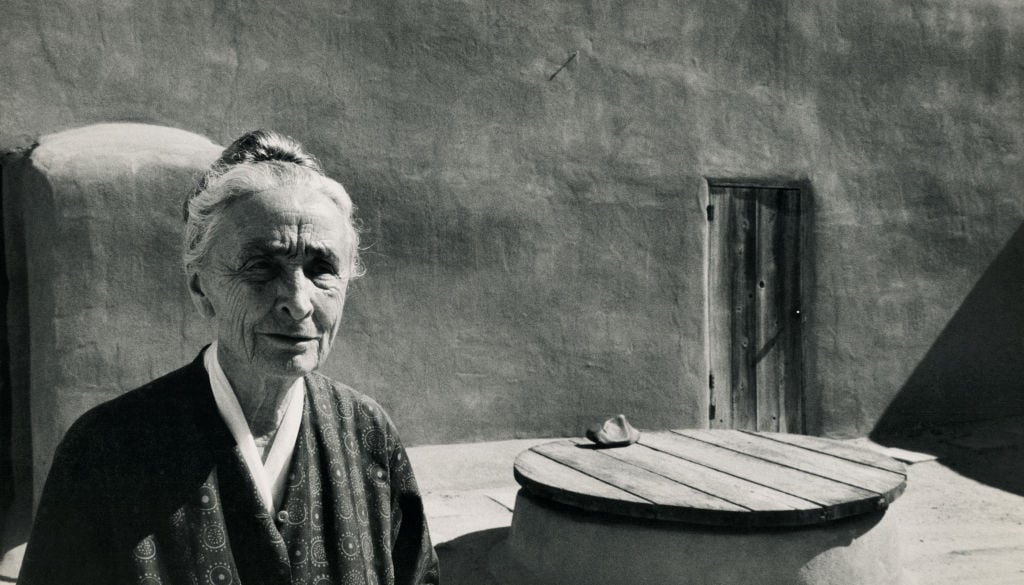

N.C. Wyeth (1882–1945) was recognized in his lifetime largely for his work as an illustrator for such famous titles as The Last of the Mohicans (1826) and Treasure Island (1883). Originally from Massachusetts, Wyeth was formally trained in private art classes beginning in his youth, studying under George L. Noyes and Howard Pyle—the latter of whom encouraged Wyeth to travel and paint in the American West, which he did for several years.

Using the earnings from his Treasure Island illustrations, in 1911 Wyeth purchased 18 acres of land in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where he built his home and studio. He worked consistently as an illustrator for Harper & Brother, Scribner’s, and The Saturday Evening Post, as well as brands like Lucky Strike and Coca-Cola. The house and studio are now administered by the Brandywine Museum of Art, just five minutes away, and visitors can take guided tours of the property, learning about the artist’s life, career, and artistic practice.

Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site. Courtesy of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

An influential figure within the Regionalist movement, Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) created paintings, lithographs, and murals that depicted life in rural America in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of his large-scale works reflect on social injustices, specifically the hardships faced by the working class. Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, and studied art first at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving to Paris in 1908 to enroll at the Académie Julian. It was there that he met Diego Rivera and took inspiration from the style and social awareness of Rivera’s work.

In 1935, Benton settled permanently in Kansas City, Missouri, and undertook several public projects in the state, including the mural A Social History of the State of Missouri (1936) for the Missouri State Capitol. The Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site are now managed by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and visitors can see the home exactly as he left it.

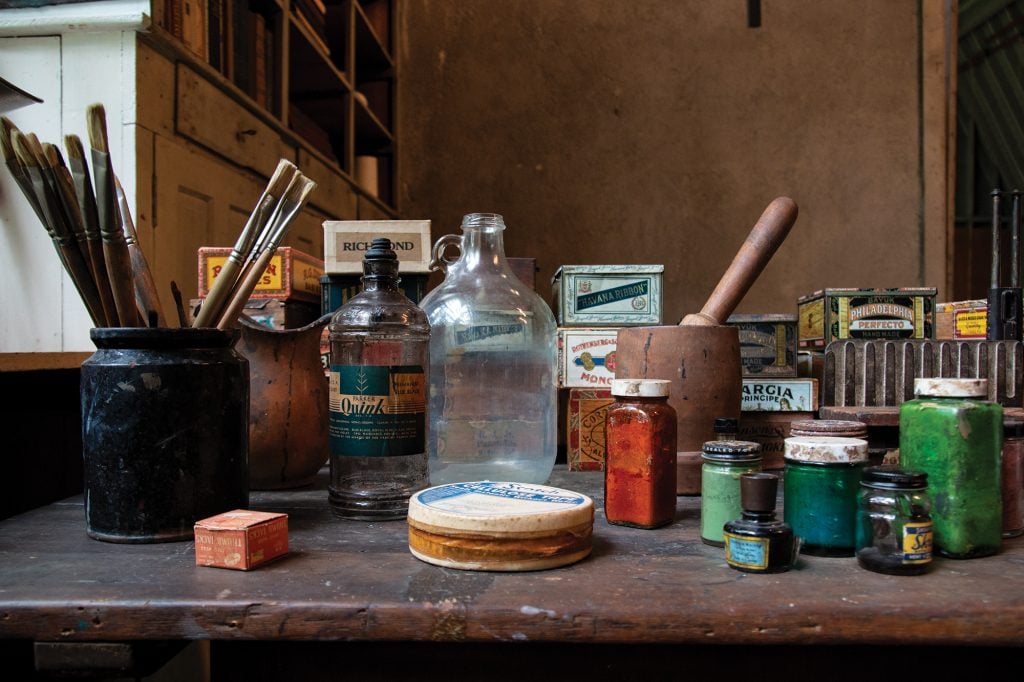

Georgia O’Keeffe on the patio of her home, Abiquiú, New Mexico (1971). Photo: Basil Langton/Photo Researchers History/Getty Images.

Best known for her modern renditions of flowers and animal skulls, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) is considered a cornerstone of 20th-century American painting. Her breakout exhibition was a solo show mounted by photographer and gallerist—and O’Keeffe’s later husband—Alfred Stieglitz in 1916 in New York City. Although much of her early work was inspired by the architecture of the city, in 1929 she began making annual trips to New Mexico, eventually moving there permanently. Inspired by the natural beauty of the landscape and the culture of the Southwest, her work took on the distinct aesthetic she is known and recognized for today.

Just over a decade after her death, in 1997, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum opened in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and today the museum maintains O’Keeffe’s home and studio in Abiquiú, which are open to visitors with reservations from March through November.

Maynard and Edith Hamlin Dixon House and Studio, Mount Carmel, Utah. Courtesy of the Thunderbird Foundation for the Arts.

Maynard Dixon (1875–1946) found widespread acclaim through his paintings of the American West. He had a unique manner of depicting clouds and used highly saturated pigments to convey the majesty of rural landscapes and helped put Western painting on the map. In 1900, Dixon traveled extensively through Arizona and New Mexico, and he later explored additional Western states on horseback with fellow artist Edward Borein. These travels greatly influenced Dixon’s work, and he became a prolific contributor to exhibitions throughout California.

Between 1925 and 1933, he worked with art dealer Beatrice Judd Ryan in running Galerie Beaux Arts, the first contemporary art gallery in San Francisco as well as a nonprofit that promoted the work of modern artists from the area. At the end of his tenure with Galerie Beaux Arts, Dixon and his wife, Edith Hamlin, relocated to Mount Carmel, Utah, where he ultimately made some of his most famous works. Since 1999, the Maynard and Edith Hamlin Dixon House and Studio have been preserved and made accessible by the Thunderbird Foundation for the Arts. The gallery and gift shop are open year-round, and guided tours of the Dixon home and studio are offered April through November.

More Trending Stories:

Whoops! A Clumsy Art Fair Visitor Shattered a $42,000 Jeff Koons Balloon Dog Sculpture in Miami